A report by the National Crime Records Bureau in 2014 displays that victims of suicide by self-immolation are overwhelmingly women (61%). A leading doctor from Kilpauk Medical College stated that based on the cases he had treated in his long tenure at the Burns Block, this figure was 76.38%. Cases of self-immolation however, go largely unreported as suicides or suicide attempts. They are usually attributed to accidents occurring in the kitchen. Another study notes that the ratio between young women (ages 15-34) and young men to deaths by burn injuries is 3:1. Again, women in the newlywed age group are seen to fall victim to these “accidents” in a disproportionately large number.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dDUC1hqhNI8&t=1s

There is clearly a gendered angle to burn injuries and suicides. This is what The International Foundation for Crime Prevention and Victim Care (PCVC) and Kilpauk Medical College (KMC) sought to explore in a knowledge sharing seminar held at KMC’s Burns Block. PCVC is an organization that works with women survivors of gender-based violence, with burn survivors being a special focus area. The seminar brought together doctors, physiotherapists, nurses, social workers, lawyers and the burn survivors themselves – all the stakeholders in the treatment and care of burn patients.

In this article, I look at the experience of women burn survivors in three parts – before the injury, while receiving care, and after leaving the hospital. This is based on the output from the seminar, and from a series of tweets curated by PCVC on @genderlogindia’s Twitter channel where they spoke about various aspects of the care of burn survivors and the challenges that women burn survivors face.

Before the injury

Burn injuries when self-inflicted, are often an impulsive decision. However, they are borne of a long history of domestic abuse and violence. It’s often a way to teach their husbands a lesson – to protest against abuse, alcoholism (which leads to abuse), or infidelity. In Tamil Nadu, there is also a history of self-immolation being used as a symbol of martyrdom – both in politics and in cinema.

Tamil films and TV serials often show women setting themselves on fire, or being set on fire in response to marital discord. One social worker from Madurai present at the PCVC seminar spoke about how a perpetrator admitted to him how he had burned his wife as a result of seeing it in the movies. Women burn survivors often say that they had no idea of the extent of the disfigurement it would cause – had they known, they would never have made that impulsive decision.

https://youtu.be/N5YnbSpNuw0?t=4m50s

This is a clip from the Tamil film Naan Petha Magane, where the wife burns herself over disagreements with her mother-in-law. This trope comes up repeatedly in Tamil film and television, and could be a big influence on the psyches of women watching these films. The disfigured body, however, is never shown on screen. Many women burn survivors say that they had no idea of the extent of disfigurement the burn would cause.

Burn injuries are passed off as “stove burns” or “accidents” at the hospital. There is very little sensitivity to the history of abuse that is usually linked to burns. There is an urgent requirement to sensitize medical staff to the incidence of domestic violence amongst women burn patients. What ends up happening is that the “accident” is taken at face value and not investigated more thoroughly.

More chillingly, burn injuries that are identified as suicide attempts can also be a cover-up for attempted murder by the survivor’s husband and in-laws. The women often themselves choose to shift responsibility for the heinous crime onto themselves, thus shielding their husband and in-laws from the law. This is sometimes done at the pleading of the in-laws. They use the victim’s position as a mother and wife to demand that she ought to be self-sacrificing in the interest of her family. The woman is exhorted to be ‘forgiving’. Sometimes this need to be forgiving is internalized by the wife herself, and she willingly shields the perpetrators from the law.

A lawyer at the PCVC seminar told us a heartbreaking story of a woman who had approached the lawyer for legal help after she had falsely testified to her burn injuries being self-inflicted. Her tragic story went thus:

She was pinned down by her husband and mother-in-law on either arm, while her husband’s brother doused her in kerosene and lit her on fire. Immediately after the act, they fell at her feet and pleaded with her to not tell the police the truth. They apologized profusely and said it had been a mistake. If she sent her husband to jail, and she was in hospital recovering from her burns, who would take care of her two children? It was therefore her responsibility as a mother to make sure her children were taken care of. So she listened to them, and staunchly told the police, even upon repeated questioning, that the crime had been self-inflicted, even signing documents testifying to this. When she returned home after hospital treatment, her husband refused to let her in the house. She was not allowed to see her children, or even retrieve her jewelry and money that was in the house. When she went back to her parent’s house, they refused her too. She was cast out from all quarters. The lawyer telling us this woman’s story helplessly told us that she had been unable to help the woman from a legal standpoint because of her false testimony that had protected her husband.

During treatment

Swetha Shankar, head of the psychosocial team of PCVC stresses on the necessity of psychological and emotional support for burn patients from the minute they are admitted in the hospital. Medical treatments often overlook this necessity, and are usually oblivious to the emotional abuse and fragile mental state of the patient. One burn survivor at the PCVC seminar spoke about how her parents were content to leave her holed up in the house once medical treatment was complete. They did not think about the psychological trauma associated with the disfigurement and injury.

The survivor said that her life only resumed after she discovered PCVC and began to attend their therapy sessions and group outings with other burn survivors. Social workers present at the seminar testified to how burn survivors often revealed after 3-4 therapy sessions the truth of their burns being not accidents or self-inflicted, but inflicted at the hands of their husbands. Thus, psychological counselling is deeply necessary to help them deal with their trauma.

Burn survivors often face intense post-traumatic stress disorder and suffer from a loss of identity. With their appearance becoming distorted and unrecognizable, they struggle with accepting their bodies. Doctors at the seminar noted how patients often slept with an old picture of themselves under their pillow to remind themselves of what they used to look like.

Added to the loss of identity that comes from appearance, survivors are also often cut loose from their families who refuse to accept them. Consequently, a lot of them lose their identities as wives or mothers or daughters, causing them additional trauma, besides the pain of losing their families. In the case of self-immolation, husbands and in-laws might guilt the survivor, asking her how she could conscionably have done this to herself when she had children to take care of. She is derided and labelled an unfit mother.

There is also the frightening possibility that the woman’s primary caregivers – her husband or in-laws might have been the perpetrators of the crime in the first place. In such instances, a safe space such as counselling is an absolute necessity.

Sadly, however, women’s post-injury recuperation period is often cut short for a variety of factors. A majority of immolation cases in Tamil Nadu arise in families from low socioeconomic backgrounds. With these circumstances, it becomes difficult for the families to pay for the long-term treatment that burn patients require. Secondly, women are the primary caregivers in the family. They are urgently needed back at home in order to take care of the children, which also cuts short their recuperation period.

After treatment

PCVC suggests that it is imperative that the burn survivors keep coming back for regular check ups to ensure both their mental and physical health. However, this is often rendered impossible when the husband cuts off contact between the survivor and her social worker.

Post-discharge therapy and counselling helps with the difficult process of reintegration into society. Burn survivors are stigmatised and ostracised from society because of their scars. Mundane activities like walking on the road, boarding a bus or attending a place of worship, become excruciating experiences of avoiding horrified stares and pointed fingers. Their appearance is never allowed to be forgotten.

Apart from the psychological damage this causes, it also harms their means of livelihood. One survivor at the PCVC seminar spoke about how she was fired from her job as a house maid because her employer told her that she gave her son nightmares. They are called ‘bad omens’. Another woman sadly recounted how she had to give up her job of selling flowers in the market because she was told, “Who will buy beautiful flowers from such an ugly face?”

Reintegration with family is often as difficult as reintegration into society. Swetha Shankar from PCVC describes how children are often bewildered and unable to recognize their mothers and are upset by their new appearance. Mothers thus have to reestablish a relationship with their children, which can be difficult for both parties.

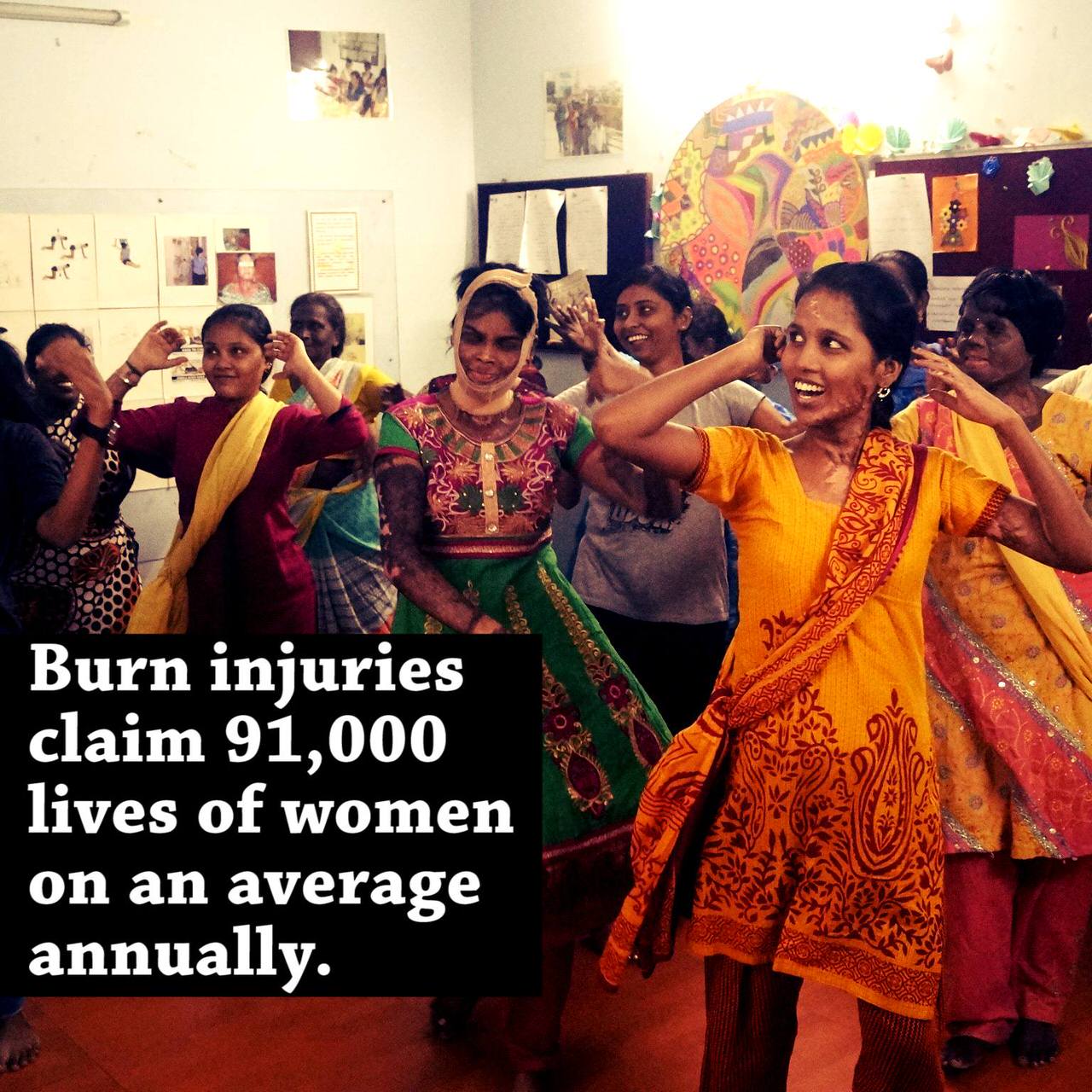

In this fraught environment, interaction and support from other survivors is a tremendous source of strength to these women. Seeing other women in similar circumstances thrive and move on with their lives helps ease the despair of new patients. This was reflected in the seminar I attended too. The atmosphere was upbeat and positive, and the survivors repeatedly spoke about how finding a community through PCVC had changed their lives significantly.

This uplifting video of a PCVC member speaking about the positivity and joy found in a group trip to the beach is a fitting reflection of the atmosphere I experienced at the seminar.

You can follow PCVC’s work with women burn survivors on Facebook and Twitter.