“We were never burned, although once I might have been when I was so terrified I tried to jump onto the stove to remove the possibility of its remaining a threat. Like most children, I thought if I could face the worst danger voluntarily, and triumph, I would forever have power over it.”

Marguerite Anne Johnson, later known as Maya Angelou, is describing the manner in which she and her brother Bailey were trained to learn their tables. Later in the book I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings (1969), Angelou writes about her rape, “The act of rape on an eight-year-old body is a matter of the needle giving because the camel can’t. The child gives, because the body can, and the mind of the violator cannot.”

I do not remember the age I was first violated. I remember what I was wearing, where I was, and how I was violated, but I cannot recall how old I was then. Psychiatrists would name this as psychological trauma endured by a victim and as one among the stages that a survivor goes through to recovery.

There were at least five other coping mechanisms that I employed, albeit unconsciously, to attempt to become ‘normal’, including minimization, suppression, hypervigilance, walking depression and dissociation. I have been known to display, in varying degrees, intense emotions, startled responses, continuing anxiety, persistent fear, and a sense of helplessness.

I do not remember the age I was first violated.

“Remember, don’t you tell a soul”. And I didn’t, because long before I learned what a rape was, I had learned that I will be blamed for it. It was easier to minimize the incident and suppress it, and I consciously did that. On the outside, I was normal – healthy in disposition and in appetite – or at least, I thought I was. At the time, I did not realize that I was only pretending to be normal.

Memory, the democratic faculty that is afforded to each individual, is among the first to reflect the trauma from the violation. The U.S. Rape Abuse and Incest National Network affirms that survivors may have affected memory, often experiencing dulled senses, difficulty in making decisions, and “have poor recall of the assault.”

To this day, I cannot recall memories in their flesh from around the time of the violation. At most, I can vaguely define the silhouettes of some incident, point that something had happened, but I cannot guarantee their factual accuracy.

I was sexually assaulted, again, when I was 14.

This perpetrator, unlike the first, was related to me on my mother’s side, and I had known for long that he loved and cared about me. For a while, I even reciprocated this emotion. The act itself however, caused fear, anger, disgust, and hatred when it happened.

long before I learned what a rape was, I had learned that I will be blamed for it.

Immediately after the incidents, I suffered bouts of contained anxiety, arranged my face in what I presumed to be natural, and participated in conversations to keep myself from accepting the reality of the previous night. More importantly, along with other emotions, I held shame, because it seemed to me that I had allowed the sexual assault to happen. However, I still could not dissociate being violated from being loved, the actor in both cases, being the same.

Angelou writes about her conundrum, “It was the same old quandary. I had always lived it… There was never any question of my disliking Mr. Freeman, I simply didn’t understand him either… I began to wait for Mr. Freeman to come in from the yards, but when he did, he never noticed me, although I put a lot of feeling into, ‘Good evening, Mr. Freeman.’”

I shared her quandary. I would wait for him, I didn’t understand him, and I couldn’t tolerate him not noticing me. I knew I didn’t want him to touch me but I wanted him to continue loving me.

***

In my mid-twenties, I entered voluntarily into feminism.

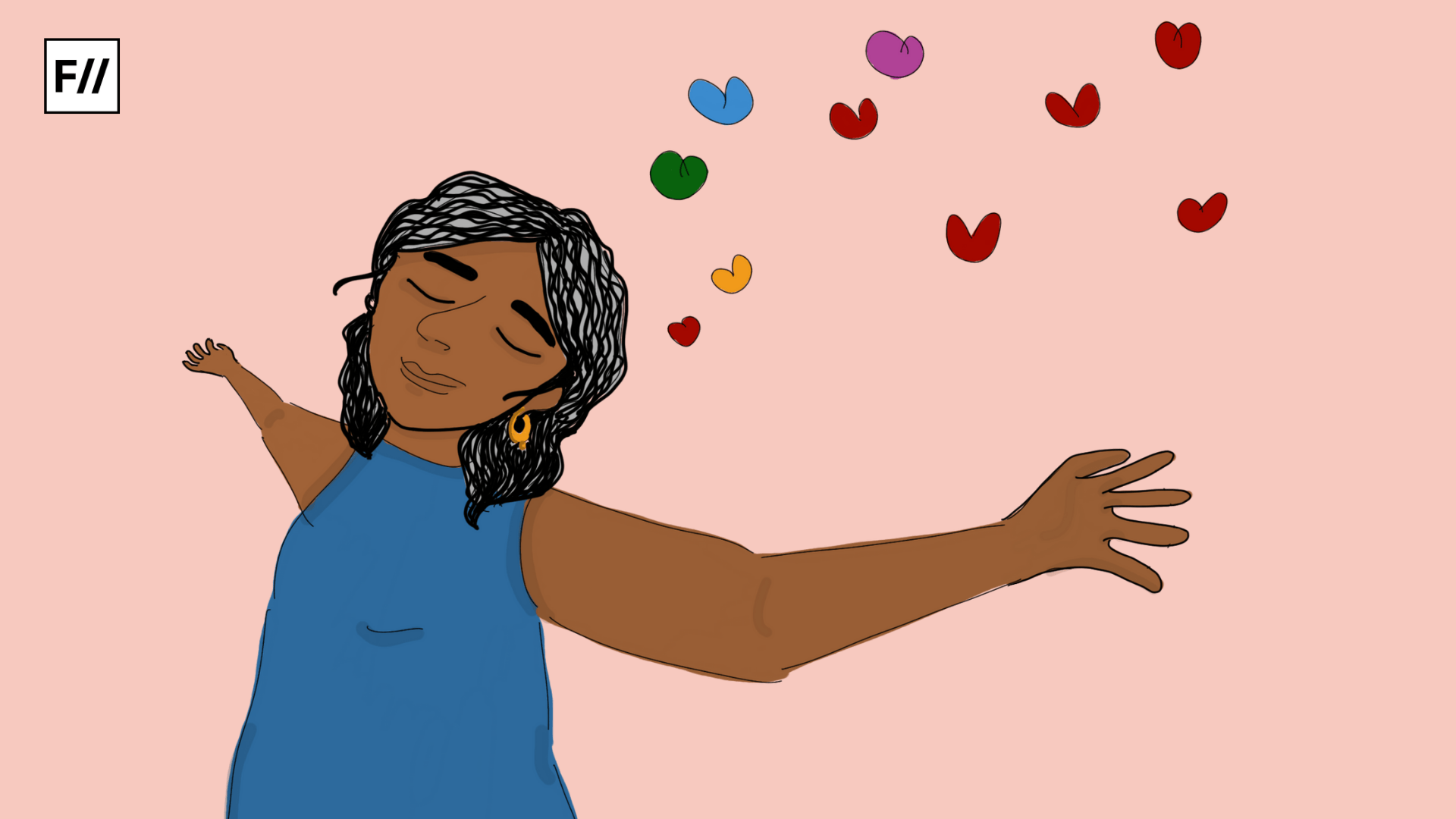

Based on the experiences, physical and psychological, I believed it was natural for me to identify as a feminist. This was a period of willed transformation, and empowered newly with feminist literature, I changed my narrative from one of victim to that of a survivor. I refused to accept that I was deformed because of my past, inclusive of my sexual abuse. I had by then disconnected with my relatives including my assaulter, and refused to include them in my life on any conditions, and this act of severance empowered me.

On one particular night however, when depression resurfaced, I realized that my empowerment had been only temporary. I had removed the perpetrator from my life but I had still to remove the perpetration.

I changed my narrative from one of victim to that of a survivor.

Burgess and Holmstrom, in their 1976 paper on Rape Trauma Syndrome (RTS) write, “The underground stage may last for years and the victim seems as though they are ‘over it’, despite the fact the emotional issues are not resolved.”

Another state, distinct from getting over it, was the raw fear of being raped that now coiled itself around me. Each time the thought would present itself, even in relatively harmless situations, I would freeze, responding to the bouts of anxiety and panic erupting inside me. On some days, I would experience this threat – the hypersensitivity to the possibility of attack – even when I was at home, safe and with people around me.

Since then, I have worked on myself with the intention to heal the wounds that I didn’t know even existed. Even though, psychologically I am in a better state, what is called as “the renormalization stage”, I know that the journey has only begun.

A few years back, my dying grandmother handed over the phone to her son. I know him as my perpetrator, my boogeyman, whose hands had reached me in the dark night. But, I spoke to him. The conversation was casual on his part, defensive and guarded on mine.

I have played with the idea of telling this secret that I have kept for fourteen years to my mother, when she tries to reconnect me with her blood, but I regress knowing that it is of little use now.

Instead, I have shared my story with close friends and some acquaintances. From some, I have received support of sanctimonious nature, some have treated it with mockery, and others have risen like grace washing over me, offering me absolution.

Today, I carry only a dissolving secret but no longer the shame.

I refer to Maya Angelou again, her 1978 poem And Still I Rise,

“Out of the huts of history’s shame, I rise/ Up from a past that’s rooted in pain, I rise/ I’m a black ocean, leaping and wide/ Welling and swelling I bear in the tide// Leaving behind nights of terror and fear, I rise/ Into a daybreak that’s wondrously clear, I rise/ Bringing the gifts that my ancestors gave, I am the dream and the hope of the slave/ I rise, I rise, I rise.”

Also Watch: A Handy Guide To Laws Against Sexual Violence | #SexualAssaultAwarenessMonth

Featured Image Credit: Mental Health America Of Licking County