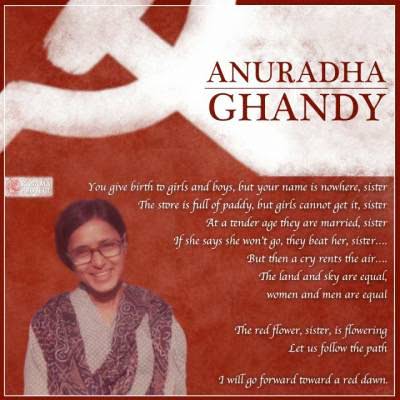

Among the countless things that Anuradha Ghandy was, irresolute isn’t one of them. She was an ideal revolutionary; a strong believer of justice with a passion for learning and knowledge, along with absolute determination to bring about change. Her fire was inextinguishable, which provided warmth to the oppressed and sparked motivation in the youth.

In the span of over three decades (1970-2000), Ghandy waged her battles at the forefront of several movements – for students, civil rights, women, workers, adivasis, and literary and cultural movements. The heights she reached stand as a testament to the strength and contributions of women of Indian history.

Born a Leader

Anuradha Ghandy’s destiny as a Marxist feminist was clear when she was born to a couple who got married in the undivided Communist Party of India (CPI) office in Mumbai. Growing up among erstwhile communists, her fierce potential was fuelled with revolutionary ideas right from the beginning. In such a liberal atmosphere, she took on avidly reading about diverse ideas, interacting with intellectuals, and actively engaging in discussions and debates.

The potential gained during her formative years got a boost when she joined Elphinstone College in Mumbai, a hub of left-wing activists.

“Anu, majoring in Sociology, was everywhere – inviting Mumbai’s leading radicals to talk about the reasons for the drought, putting up posters that proclaimed ‘Beyond Pity’ and urging students to get involved with the crisis in the countryside, defending this stand against those who felt a student’s role must be limited to academics and at the most, ‘social work’,” wrote Jyoti Punwani, her college and lifelong friend for Times of India.

From there was no turning back. She went on being an active social worker during the time when communist ideas were sweeping the world. After joining the Progressive Youth Movement (PROYOM) and associating with Naxalbari, she led a number of initiatives which not only influenced various progressive movements, but also imparted a huge contribution towards the growth of rural and tribal women. Inspiring countless women to practice leadership, she pioneered intersectional feminism during her lifetime by fighting for and including women from lower castes and classes.

Structural Oppression: Combatting Caste

In the spur to bring change, she abandoned her high-profile life at Mumbai and shifted to Nagpur, a place totally new to her. From then on, she engaged and led activities of trade unions and Dalit groups. Her ability to mobilize workers of the unorganized sector was noteworthy. She propagated Marxism, and strongly believed in the potential of the working class to fight capitalist forces to end exploitation.

She worked in slums and interacted with Dalits, learning about their problems. Her awareness and sensitivity toward the brutal and discriminatory behaviour faced by them influenced much of her work as a change-maker. She was in the forefront of the sweeping ‘Dalit Panthers’ movement of 1974.

She had abundant knowledge of the Indian caste system, as reflected in her two-part essay- ‘The Caste Question in India’ and ‘The Caste Question Returns’. Right from the origins of caste system 3000 years ago to the emergence of Brahmanism to post-colonial anti-caste movements, the essay offers a deep insight to the kind of learning Anuradha pursued, full of critique.

“In India, capitalist growth (initiated, nurtured and led by the imperialist powers) is of a distorted and warped character which superimposed new factors on the old existing relations of production – it does not seek to smash the old relations. So, along with the supercomputer you also have the wooden plough; with modern telecommunications and TV you also have Sati; in spite of the ‘modernisation’ of the cities you also have the deep-rooted caste sentiments” states the second part of the essay.

Her informed opinions tied with an ambitious character made her a strong ally in the anti-caste and working class movements. She disseminated her ideas through public speeches, writings and social work.

A Woman for Women

Among Anuradha Ghandy’s exceptional work is her contribution towards the upliftment of women, particularly belonging to rural and tribal areas. She bridged the gap between women and revolutionary groups, and thus encouraged women to take action and destroy the shackles of patriarchy. She used to hold classes and meetings where rural and tribal women were educated about the movement and how it would improve their condition, making them self-dependent and free from oppression.

“By propagating women’s nature as non-violent they are discouraging women from becoming fighters in the struggle for their own liberation and that of society”, is one of the many critiques she maintained on the trends on feminism, as stated in her article ‘Philosophical Trends in the Feminist Movement (Part I)’.

She represented the communist woman activist in the feminist milieu, and was highly critical of the bourgeoisie feminism which was gaining momentum. She strongly advocated the inclusion of Dalit and lower class women in the movement. In an interview with Poru Mahila, the organ of Krantikari Adivasi Mahila Sanghatan, DK, for their March 2001 issue, she explained,

“Now they have become propagandists for feminism, meaning patriarchy is the main problem of women, we have to fight only against patriarchy. But patriarchy has its roots in class society. In all societies it is perpetuated by the exploiting classes, i.e. feudalism, capitalism and imperialism. So fighting patriarchy means fighting against these exploiting classes. But the feminists are against recognizing this. They believe women’s conditions in this society can be changed by politically lobbying with the governments and by propaganda alone. In reality this feminist stream today is representing the class outlook and the class interests of the bourgeois and upper middle class women in the country.”

Inking the Revolution

Anuradha Ghandy was an outstanding intellectual with a creative bend. She penned down her ideas and messages in numerous essays, articles and other pieces of writing. Plentiful material on Marxism was produced by her in English and Marathi, covering different trends of the ideology and the misrepresenting nature of the trends. Satyashodhak Marxvad was an exceptionally elaborated article written in Marathi, about the Marxist view-point of Dalit struggle and liberation.

Critical of bourgeois feminism, Ghandy strongly advocated for the inclusion of Dalit and lower class women in the movement.

Being a prolific writer, she was an active contributor of various revolutionary magazines in Marathi, English and Hindi under different pseudonyms. Apart from that, she wrote many theoretical and ideological pieces particularly associated with Dalit and women’s questions.

Fighting till the end

She was arrested many times, and spent most of her life underground. But such was the dedication of Anuradha Ghandy, that she had returned from Jharkhand after taking classes of women’s question among tribals only a week before her death. Jyoti recalls:

“Anu managed to evade arrest for so long, it was an indicator of the ruthlessness with which she effaced her identity. This, of course, meant isolating herself from all those who would have given up everything to nurse her. There was another way she could have recovered, even while underground. Anu could have followed medical advice and given herself the break her body so badly needed. For someone so important to the Party (CPI-Maoist), it might well have allowed it. But that wasn’t her style.”

The country lost one of its fiercest leaders on 12 April 2008 to a virulent strand of malaria. Her story continues to encourage people who are oppressed, giving them the strength to strive and end their suffering. Her intellectual bestowments in the form of her writings are still used by students, academicians and other intellectuals. And most importantly, she illustrated her ability to overcome patriarchal norms to rise as a leader by leading an exemplary life, which will go on to inspire all the women who believe in change.