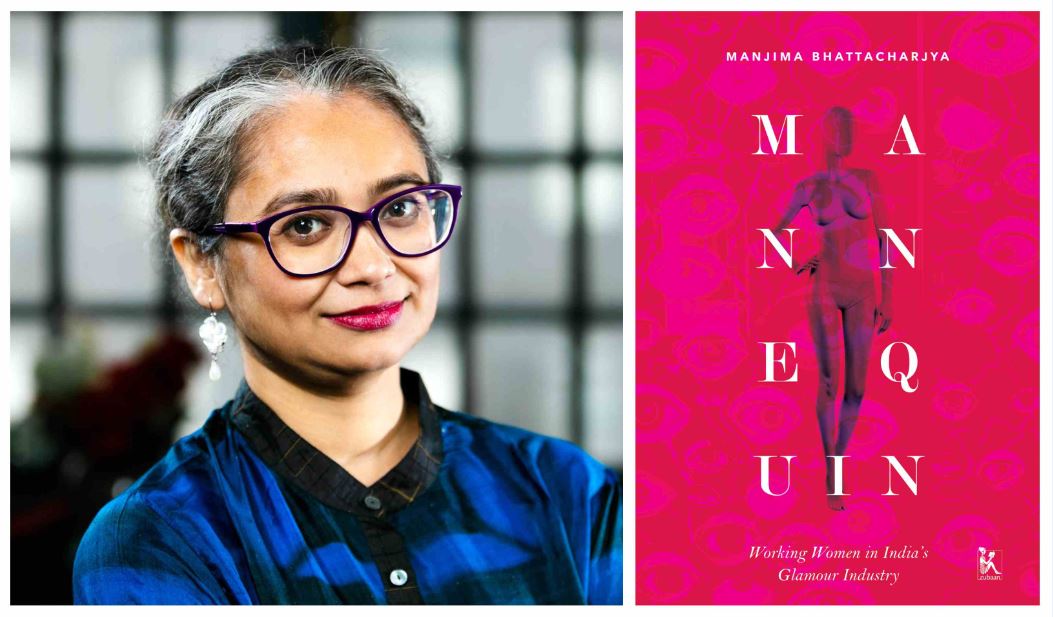

Mannequin, by Manjima Bhattacharjya, is a feminist take on the fashion industry. It bridges the gap between fashion and feminism. The book tells the stories of women from small towns and different economic backgrounds and traces their journeys as models. Some of these women are print models, some ramp models, while some entered the industry with the hope of making it to the small screen.

Mannequin magnifies these stories, tells us what made these women take up modelling as a career, what challenges they faced, and how they dealt with them. The book brings personal conversations into print. In her book, Manjima Bhattacharjya talks about how feminism is a diffused idea between the activists and the models in the fashion industry.

Ironically, many activists were completely against the existence of any such fashion industry until a few years ago; the evidence to which can be traced to the 1996 Bangalore protests against the Miss World pageant, where activists were questioning the ‘commodification’ of women. Manjima Bhattacharjya describes how, from protesting and demanding the ban of beauty pageants, society has become more sex-positive, and the struggle has shifted to being about workplace rights and protection against exploitation of the models.

Also read: Can Fashion And Feminism Go Hand In Hand?

Mannequin traces the careers of thirty women, with personal accounts of each, describing their lives as models. Some are insightful, like the story of Kamal, who belongs to a Rajasthani Marwari family and has talked about how she was tagged ‘shameless’ by the people in her town, but was also later called to inaugurate local beauty parlours after her stint at the Miss India pageant.

This account also tells us about the inherent hypocrisy among the Indian population, who would run after the same person they had once labelled as a misfit, after they gain national recognition. Our need to be associated with prominent and influential people has been portrayed beautifully, while also precisely pointing at our tendency to mark the same people as outcasts according to our comfort.

The story of another model, Palash, if read closely, showcases the reality faced by many women who venture into the industry to build a more liberated lives for themselves, but end up being trapped within the unforgiving nature of the business. Mannequin does not romanticise the journey of these models by tagging them as a ‘rags to riches‘ story as perceived by many.

Monthly magazines continued to promote the idea of tradition, asking women to be ‘modern yet traditional’.

Mannequin truthfully captures the stories that stand testimony of how tradition continues to be the most important aspect of the Indian households. It also shows how for some women, modelling has been means to break free from the culture of their upper and middle-class homes and find liberty by not falling back on marriage as a way to create a life.

Fashion in India grew as a result of globalisation. As Western ideas seeped into the Indian minds, so did the products. Fashion in India was initially, as pointed out in Mannequin, a way to promote the Indian textile in the global market; but the craze around fashion spread like forest fire in the minds of the Indian upper and middle-classes. For Indian housewives, fashion came in the form of monthly magazines like Femina, which were “informative in nature, like a consultant” and did not judge.

Evidently, somewhere down the line, these very magazines, billboards, and televised reality shows became responsible for making Indian women conscious and insecure of their body and looks. Monthly magazines continued to promote the idea of tradition, asking women to be “modern yet traditional”. The line, “Indian women were craving glamour”, reveals how business giants used the vulnerabilities of the Indian wives to sell their products.

None of the women interviewed by the author were from the scheduled castes or the scheduled tribes, or identified themselves as Dalits. The conversation was exclusive to women belonging to the upper or dominant castes of their respective communities. Bhattacharjya does not comment on whether or not there are models from these social strata in the business and whether they face any discrimination whatsoever.

The text is restricted, at large, to upper caste women, albeit from different backgrounds and classes. One can find instances of conversation with the women from the Northeast which provides us with an insight on how things can be different for some women simply because of where they came from.

these very magazines, billboards and televised reality shows became responsible For making the Indian women conscious and insecure of her body and looks.

Mannequin provides a bird’s-eye view of the modelling industry. It does not draw a solid line between feminism and fashion; it integrates both of them, emphasising on why feminism is important in all the industries, and why the rights of the working-class women has to be protected, regardless of what the work is.

Mannequin puts fashion under a light which is neither too positive, nor laced with the same questioning glare of the feminist movements, as was the case in the 1980-90s. Back then the activists were questioning the shift of priorities, with posters that said “Khane ko nahi roti, Dhoondne chale beauty” (We have no food to eat, But we are searching for beauty).

We as a society have come a long way from the traditional view of regarding some professions as demeaning to women and oppressive in nature, to advocating for the right of women to have the freedom to choose these professions and live a life as respectful as any other. It lets the women speak for themselves sans the judgement. Mannequin is not a brief overview of the lives of the models, it dives deep into the analysis of the lives of these women. In its non-judgemental nature, it simply states the facts, letting the readers decide how they want to read between the lines.

On the downside, Mannequin describes the feminist movements of the 1980s and 1990s and the takes of feminists, but does not state what the models have to say about it. A statement issued by women’s groups in 1996 stated, “Our protest is against an event that is a glamorous symbol of the globalisation process that is drawing all Third World countries and developing economies into the highly exploitative international markets.”

Though the book traces the careers of the model from 1980s and 1990s, it does not take into account what these women have to say about these protests, or what they feel about the body positivity discourse. Mannequin does not feature the testimonials of women apart from models in the fashion industry – designers, stylists, makeup artists, hairdressers. It mentions the capitalist exploitation of the industry on women who wear the creations of the designers, predominantly men; but does not give us an insight into what the female designers have to say.

feminism is important in all the industries and the rights of the working-class women has to be protected, regardless of what the work is.

What Mannequin does indeed do, is shed light on how beauty pageants have evolved over the years, from a qualifier for upper-class women to a way to create a livelihood for themselves. It tells us how women were initially trained to be ‘good homemakers’, with the prizes at the beauty pageants being iron, fridge, etc, to international modelling contracts.

Mannequin talks about how fashion has led to many women breaking out of tradition and has created a new working class. It also points out at the initial exclusion of them, through protests against beauty pageants, as they were not pointing out the fact that some women indeed found this opportunity liberating.

Mannequin beautifully expresses how women are shamed on the basis of their choice of livelihood and associates professional choices with those connected to society’s definition of morality.

Mannequin is a good read for those looking for an unbiased view of the fashion industry. It also lets us see fashion as an industry, a formal working space. It fits feminism and fashion into the same page. As Manjima Bhattacharjya, in the year 2015, a decade after she started her research, sits in a fashion show, says, “I am almost fashionable. And still a feminist.”

Also read: The Changing Face Of Indian Fashion: Can It Be Feminist?

Featured Image Source: Indulge Express