Posted by Roshna Humayun

Padmarajan is a Malayalam writer and film maker whose works are widely known for their realistic portrayals of human predicaments. His works throb with a sense of honesty. Not the brutal kind though, trumpeting truth declaration. The honesty of his works lies in his characters – in their most casual lines and silences. His works have covered topics from sexuality to mental illness to love and loss. But his characters are untouched and unperturbed by the abstract theories and vocabulary around these concepts. They deal with it in concrete and everyday terms.

it is in his repertoire of works that I have seen some of the most real, layered, complex, self-compassionate, and brutal women characters ever.

This mode of treatment makes his works elusive to easy labelling using the metanarratives. For example, none of his works would easily come across as ‘women centric’. However, it is in his repertoire of works that I have seen some of the most real, layered, complex, self-compassionate, and brutal women characters ever.

In his movie Thoovanathumbikal, we have Clara. In the movie, Clara is someone who got into become an escort sex worker willingly. The unapologetic and glad will with which she ventures into it is clearer in the novel Uddakkapola by Padmarajan, on which the movie is based. She did not become a sex worker standing in the cusp of an inevitable life edge. It was more out of the general boredom and lack of freedom in her life, as someone belonging to a small fishing community village in Kerala.

Also read: On Prithviraj’s Statement And The Long History Of Misogyny in Malayalam Cinema

She wants to travel and see the world. Her sense of pride and respect for this profession is not merely a defence mechanism to make her life as an escort bearable. It can be seen from the only instance in the movie/novel when Clara expresses guilt and shame – when she professionally cheats on the pimp who introduced and made her an escort. Only someone who has a genuine respect for the profession can believe the pimp to be worthy of her consideration and respect.

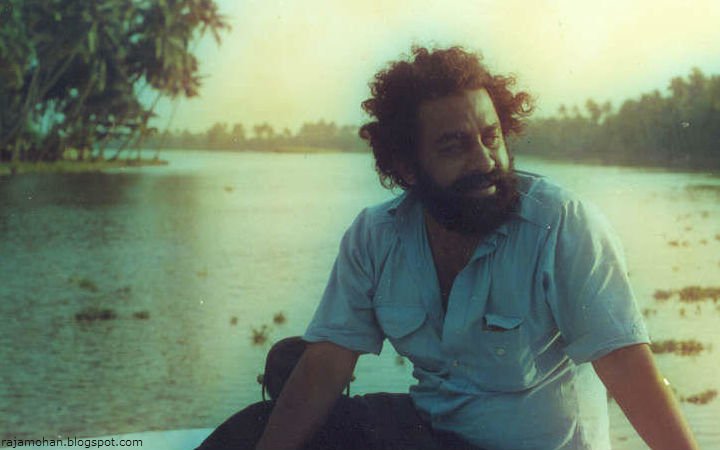

Image Source: Film Beat

Clara cares for herself enough to go after and get what she wants in life. She does not let the society’s moral codes to make her feel bad about the path she chose for it. At the same time, she is not very keen on putting on a theatrics featuring her choice and freedom. She manages to get away from her home to become a sex worker without stirring up a hullabaloo and with the help of some white lies. Her capability to value herself does not affect her love and compassion for others. She does not want to hurt her family. She respects the guy who helped her get into this profession and harbours love for someone who came into her life as a client.

While the love Clara has for others is primarily shaped by her commitment to self-care, in Aswathi of Padmarajan’s Vadakakku Oru Hridayam we see its grammar changing. Aswathi is quietly but strongly resilient with her need for love and to love. She needs it in all its glory, its mundane, nurture, lust and nuances. When her parents cut in her relationship with Kesavankutty by getting her married to Parameswaran, it is her resilience which makes her fall for her husband. His inability to consummate the marriage makes her leave the marriage and return to Kesavankutty. Her torments of guilt for leaving her husband irks Kesavankutty who in turn leaves her. Then when Sadasivan who adores Aswathi and has always watched her life from a distance proposes to marry her, the very same resilience makes her get into a second marriage with him. She is bruised by her need for and to love. But the pain and suffering does not stop her from searching and falling for it.

Image Source: Hungama

Deshadanakkili Karayarilla tells us the story of Nimmy and Sally, two high school girls who finds out that the most meaningful relationship of their lives is the one they share with each other. Sure, it happens in the absence of a good relationship with their parents. Sure, it happens in the absence of any lovers in their life. Still, to identify their relationship value outside the norms granted by the label of friendship is not easy. It calls for a great amount of listening. Listening to one’s feeble but persistent inner sound that is constantly trying to tell you something amid the cacophony of societal conditioning and discourses.

Image Source : Old Malayalam Cinema

A very similar woman soul can also be seen in Padmarajan’s Novemberinte Nashtam. Meera has not known the love of her parents. She only has an elder brother who is committed to love and take care of her. When the guy with whom she had a relationship in college casually leaves her after the college, she does not raise voice or react violently. However, over time she quietly slips into depression and mental illness. Meera shuttles her life between mental hospitals and home for the years to come. But she still harbours love for the man who made her slip into the abyss. It gets punctuated only when she sees her brother with a broken forehead, from a duel he had with the love of Meera’s life. Meera’s love, for both her brother and her lover, is resilient. It is resilient to lack of reciprocity and the hurt it caused her. However, it is not stubborn. Despite her compromised mental faculties, she subjects it to reason. Albeit reasons of her heart.

it is his women characters who come out with a unique freshness. We see them confirming and subverting notions of gender, purity and sacrifice.

In the movie Arappatta Kettiya Gramathil, we hear the stories of women in a brothel. The story revolves around the escape of the chaste Gowrikutty who was brought in against her will. However, a more interesting character is another inmate of the place, Devaki. From the little peek we get into her story, we understand that Devaki was married and it was her husband who brought her in there. However, Devaki is aware of the option she had to run away and says she is there because she has to live for and take care of her son. The way she smiles and talks and behaves does not scream of of the usually portrayed abusive brothel background. She has the quiet and warm hospitality you would typically find in the woman of a household. Though she tries to mix it up with some flirting, we see primarily a gracious host as she serves the clients with food and drinks.

Image Source: 101 India

We then have the Sophia of Namukku Parkkan Munthirithoppukal. After being raped by her stepdad, she cries for herself. But more for losing her mother and stepsister, whom she thinks will now be estranged from her because of the rape. She has a soft smile on her face in the last scene of the movie, as she is going away with her lover Solomon. There is generous ensuing of inadvertent but strong reclaiming by Sophia, of the power the rapist had vested in himself. We witness a slice of someone’s life in all its poignancy. It is drizzled with hope and agency. Not in copious amount that makes the slice too sweet like a piece of diamond whose shine can blind you. But just enough that pursuits of our life, whatever it be, see some light at the end of the tunnel.

Also read: Cinema Of Male Apathy: Rape Scenes In Malayalam Films Through The Ages

This in no way covers the many fascinating forms of human life that Padmarajan has taken on in his short stories, novels and films. The honest and organic setting of his works lend his characters, men and women, a shape and texture of its own. It is like how a lump of clay thrown into a potter’s wheel develops within the soft touch of the potter’s cupped hands. In many of his works, including the ones mentioned here, can be seen intriguing male characters as well. However, it is his women characters who come out with a unique freshness. We see them confirming and subverting notions of gender, purity and sacrifice. We see them keeping their heads down and heeding to what their own lives and inner selves have to tell them. We see them picking up the fabric of life in its whole with all of its strands, stitches, holes, and patchworks.

Roshna Humayun is a Development practitioner and has academic interest in the issues of religion, gender, and mental health. She finds her centre in the routine and mundane of everyday life. And in reading Vaikom Muhammad Basheer. You can follow her on Twitter.

Featured Image Source: Silver Screen

Watched thinkalazhcha nalla divasam as an adult recently and realized caste politics of the movie is extremely problematic, have lost complete respect for the director.