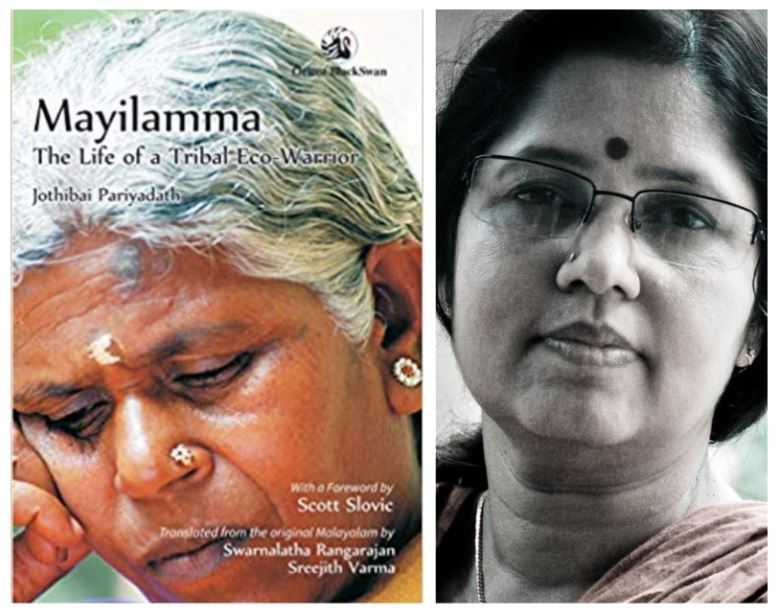

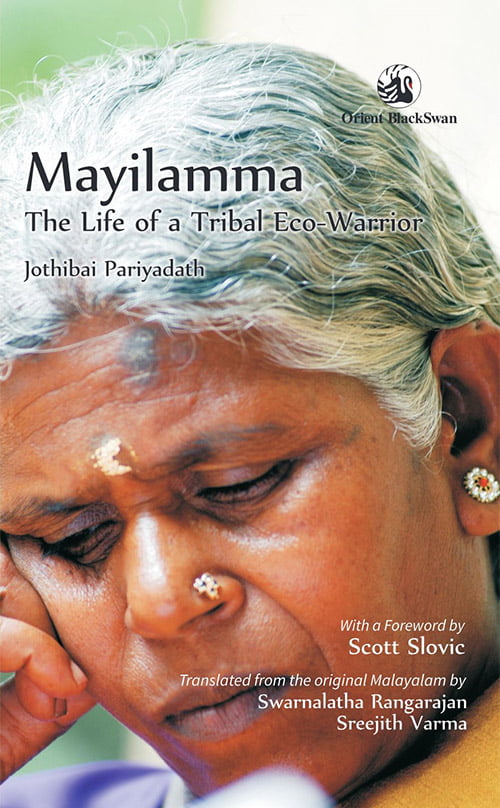

Mayilamma: The Life of a Tribal Eco-Warrior is an autobiographical account of an Adivasi woman who emerged as a leader in her community’s struggle against the Coca Cola company in Plachimada.

Mayilamma’s story was transcribed by poet Jothibai Pariyadath in 2005. The book initially came out in Malayalam in 2006 with the title Mayilamma: Oru Jeevitham. The English edition which came out in 2018, was translated by Prof. Swarnalatha Rangarajan, of IIT Madras and Dr. Sreejith Varma, of Christ University. The translation makes Mayilamma’s story accessible to a wide global readership.

The Anti-Coca Cola campaign in Plachimada may be seen as one among the trajectory of many grassroots

Environmental degradation and the loss of livelihoods

In 1998, the Coca Cola company acquired the permit to set up a bottling plant in Plachimada, a relatively dry village on the Tamil Nadu-Kerala border, which was near the highway.

This is an intimate testimony of the perils resulting from the over-exploitation of nature, a reminder of the limits of nature, which cannot provide and restore indefinitely.

Elected politicians promised the residents that the presence of the company would usher in job opportunities. When the factory began to operate in 2000, however, the only jobs available to them was that of cleaning bottles. The factory extracted 1.5-2 million litres of water from the ground every day. Its dumping leached into the soil, destroying its fertility.

Six months after the factory began to operate, the quality of water in the wells had either depleted or considerably deteriorated. The water left the skin itchy, and the cooking inedible, leaving people tired and ill. Moreover, fields which once grew paddy were now left uncultivated, resulting in the loss of agricultural livelihoods.

The company brought in tankers of water, albeit from questionable sources, to meet the water requirements of the colony, but this was no permanent solution. The degree of pollution and extraction was exorbitant. The Adivasis decided to protest against the company, demanding an end to its operations in the area and monetary compensation for the sufferings they endured.

Grassroots resistance

The protest began peacefully on 22 April 2002. For months, the people gathered in a pandal in protest, forgoing work. When the men went to work, eventually, the women stayed on.

In this situation, Mayilamma emerged an unlikely leader. She felt deeply about nature, and lamented the destruction of the environment. She had a premonition of the ecological disaster much before it came into being. After having listened to speeches delivered by activists who came from outside in solidarity, Mayilamma learned to speak herself. The words came naturally to her. If Sonia Gandhi had come to Plachimada, Mayilamma would have told her:

“There is a small well in front of my house. All these days, we were drinking water from that well. Now the water is not good. We are not against you giving any company a permit or an award. But can you bring the good water back to our well?”

Mayilamma’s narrative

Mayilamma seamlessly weaves two stories into her narrative – the story of her life, and the story of her community’s struggle. The narration shifts across time and space, as Mayilamma juxtaposes her past with the present, self with

The book illustrates, as the translators put it in the introduction, that the subaltern can indeed speak.

Mayilamma evokes a sense of nostalgia for ways of living and knowing lost in the wake of modernization. She belongs to the Eravallar tribe, whose language and rituals are endangered. One gets a glimpse of indigenous knowledge systems which are being lost, especially knowledge about medicinal herbs. Caste is deeply embedded in the narrative, as the struggles of Adivasis, especially surrounding claims to land, are recounted. Mayilamma’s personal struggles – as a young widow who decided not to remarry determined that her children receive the education she could not, are also emphasized. The Anganwadi is an important site in the story.

Locating the text in wider context

The struggle against Coca Cola in Plachimada is one among many ecological and tribal movements in the state of Kerala. It is not the only grassroots movement against Coca Cola. Mayilamma’s biography too may be placed against a trajectory of such biographies.

Also read: Chuni Kotal: First Woman Graduate From Lodha Tribal Community

Mayilamma interacted with Medha Patkar and Vandana Shiva. A World Water Conference, organized by Vandana Shiva, was held in Plachimada in 2004, and a declaration was drafted. Factory operations came to an end in 2004, but the Adivasis remain to be compensated as governments elected at the state and centre keep shifting responsibility.

Mayilamma passed away in 2006. The appendix to the text contains two poems written by Jothibai Pariyadath after Mayilamma’s death. It also contains interviews of Jothibai Pariyadath, Mayilamma’s children, and Vilayodi Venugopal, Chairman of the Plachimada Anti-Coca Cola Agitation Committee. The translation retains the vernacular flavour of the narrative.

Years after the closure of the factory in 2004, the wells remain dry, and women continue to hike long distances to fetch water.

Also read: Dharti Aba Birsa Munda: The Indian Tribal Freedom Fighter

Mayilamma: The Life of a Tribal Eco-Warrior reveals the dark side of globalisation and consumption, and flaws in the logic of capitalism and development. It is an intimate testimony of the perils resulting from the over-exploitation of nature, a reminder of the limits of nature, which cannot provide and restore indefinitely. It is also a testimony to the power of grassroots environmental movements. I highly recommend the book. Reading it was equally insightful and delightful.

Featured Image Source: ASLE