Editor’s note: #DesiSTEMinist is a campaign to celebrate women in the field of STEM and highlight their contributions.

Posted by Nishanti Sudhakar

In 2018, a Canadian optical physicist and professor at the University of Waterloo won the Nobel Prize in Physics for the invention of chirped pulse amplification in the mid-1980s, a technique to effectively intensify the power of laser pulses. When you picture this celebration of scientific prowess, what are you really imagining? A wise, grey man with intelligent eyes humbly accepting an award for the blood, sweat and tears he has shed and years of hard work. The physicist in question is Donna Theo Strickland; only the third woman to win a Nobel Prize in Physics after Marie Curie in the 1900s and Maria Geoppert Mayer 60 years later.

Our image of what a Nobel Laureate should look like is primarily due to years of conditioning of seeing predominantly male figures (97% of all Nobel Laureates) in STEM.

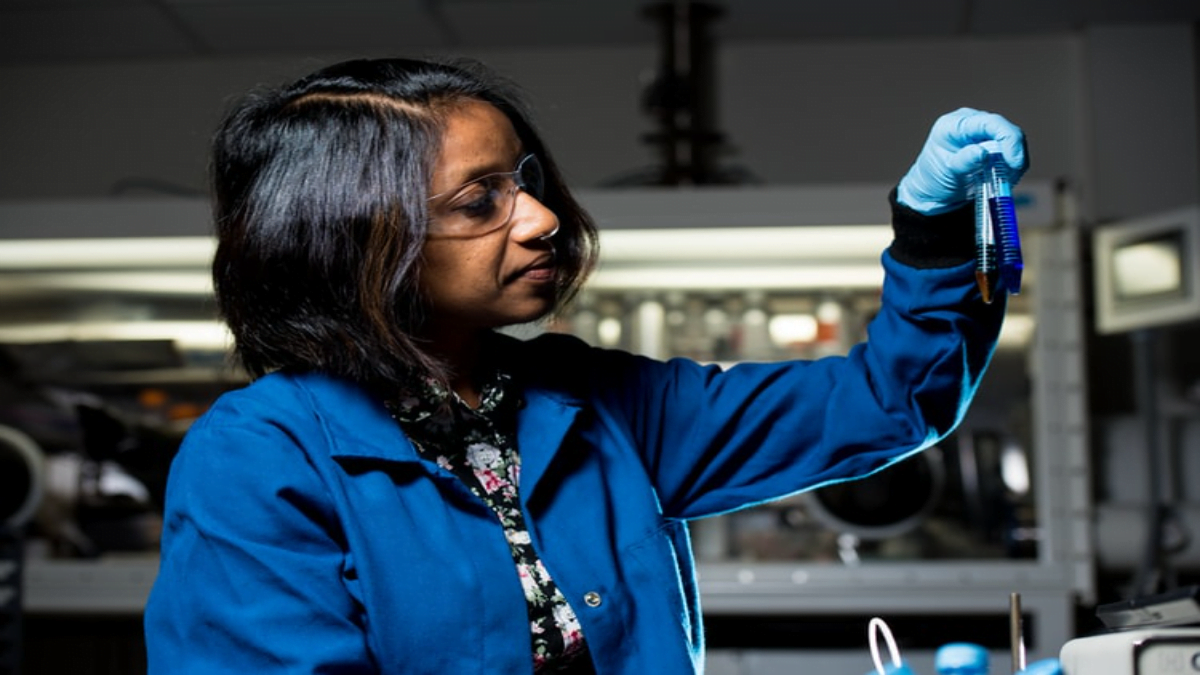

I was asked to provide an insider’s perspective to the gender bias that seems so apparent in STEM. What is it like to be a woman within the Indian scientific community? In my smallish career in the world of molecular biology, I have had the pleasure of working on cutting edge research in three reputed laboratories. Not once in my four years as a scientist (and many more as a student) have I had the misfortune of facing discrimination at the workplace based on my gender (or witnessing fellow women scientists being subjected to it) so I am ecstatic at the very least, to report based on personal experience that there is hope for women in STEM.

However, there is no debate that women have always faced and are continuing to face monumental obstacles when it comes to making a career in any field when compared to their male counterparts. Why are 97% of all Nobel Laureates men? Why is there such an exclusion of women in STEM? Are women biologically not as skilled as men in science? Or is our society to blame for conditioning us to believe that STEM is a male-dominated agenda?

There is overwhelming evidence that suggests that women are considered a minority in the workplace and an exception when they succeed.

While girls are no doubt different than boys, with the latter shown to be better at spatial tasks and the former with verbal recall tasks, there is no substantial evidence that these differences contribute significantly (or at all) to performance in STEM. However, by their very nature, girls are seen to be more anxious than boys and thus do worse on tests even though they do as well as boys in class work. The international student assessment (Pisa) compared test results of girls against those of boys in 40 different countries who were subjected to identical mathematics and reading tests.

On average, girls were reported to be more anxious than boys and this reflected in their performance. Overall, the girls’ scores were up to 2% lower than that of boys. However, the gap varied across different countries, with more gender-neutral countries (countries that treated men and women equally) like Norway and Sweden having a smaller gap than more gender biased countries like Turkey.

Studies have also shown that male scientists are more likely to be referred to by their surname and female scientists with their given name; which wouldn’t be much of an issue if it wasn’t for the fact that individuals referred to by their surname are more likely to be perceived as eminent and more deserving of awards (“One study reported that calling scientists by their last names led people to consider them 14% more deserving of a National Science Foundation Career award” according to BBC.com). Most statistics on the subject point to the under-representation of women in STEM over several decades to this day.

So is gender bias socially constructed? It appears so. There is overwhelming evidence that suggests that women are considered a minority in the workplace and an exception when they succeed. This is implicit bias – a subconscious, involuntary and even unintended bias that has caused women grief over centuries.

Also read: Do Men In STEM Hate Women? | #DesiSTEMinist

Now that the facts have been laid out and the statistics stated, it is almost safe to conclude that the future for women in STEM is bleak at best. With that being said, I would like to add to this unfortunate story a perspective of my own.

I am a woman in STEM.

I am a 24-year-old south Indian girl who came from the very society that has bridled my kind for centuries, if not millennia. I wondered at what the human cell was able to do and in awe of how such order was extracted from what was otherwise pure chaos. This order which not only allowed its survival but also its constant adaptation; improvement even. I wanted to learn more and so I did, with the full support of family and staff. When I began my career as a scientist with cautious optimism as well as scepticism, I was not disappointed.

Perhaps the gender bias is not so much in the workplace as we had imagined, but more so at home.

Despite the statistics that have shown history to provide only toxic work environments for women, what I saw was far from this truth. My research has always been given due recognition and I have always been encouraged, just like my peers of the opposite gender, to assist those who lacked any knowledge that I might have accumulated.

I have watched proud parents and husbands send their daughters and wives on amazing adventures in science, encouraging them to do great work and make their time on this planet one of substance. I have seen mothers drop their children off at school and go about the rest of their day as the head of a research group; doing great science, making changes to the world that had once tried to hold them back.

My very first endeavour as a researcher was in India. While my laboratory had two male group heads, there was an exact equal of scientists from both genders. To the best of my knowledge, this was purely coincidental, as the company had no gender-based employment policies. My second laboratory was in Australia, a country with statistically lower sexual discrimination than India even and this reflected in the workplace, which had an unruly, unintended mix of both men and women. There were as many female group heads as there were male, and as many scientists from each gender as the other.

Perhaps the gender bias is not so much in the workplace as we had imagined, but more so at home. I have known peers who have had to fight to be allowed to have a career and even higher education. Unfortunately, not all families have been as conducive to careers as some of ours are. Being constantly told at an early age that they need to focus on family over all else because that is what women are meant to do can have a rippling effect in performance in later years due to the anxiety built through the conditioning.

While I admit that I may not have been exposed to the nuances of discrimination and I will allow that perhaps sexual discrimination becomes more apparent as I further my career and that I might even be an isolated case, I have reason to believe that with my generation we might have hope. The very fact that I (and everyone I have worked with thus far) have not felt discriminated against is great news for the women in the scientific community. We are slowly becoming more commonplace in a work environment than we were previously.

Also read: How My STEMinist Mother Paved Way For My Future In STEM | #DesiSTEMinist

Marie Curie, a personal hero and the first woman to win a Nobel Prize (in physics ) said, “I was taught that the way of progress is neither swift nor easy” and how right she was. The important thing is that there

Nishanti Sudhakar is a molecular biologist who aims to help save the world by developing environmentally conscious and alternatives for fuels and plastics. Her current research is focussed on metabolic pathway engineering of microalgae for sustainable biofuel production and wastewater treatment. You can follow her on Facebook, Instagram and check out her blog.

Nice article my daughters will be happy to read