Posted by Shruti Chakravarty for Mariwala Health Initiative

The Role of the Mental Health Community

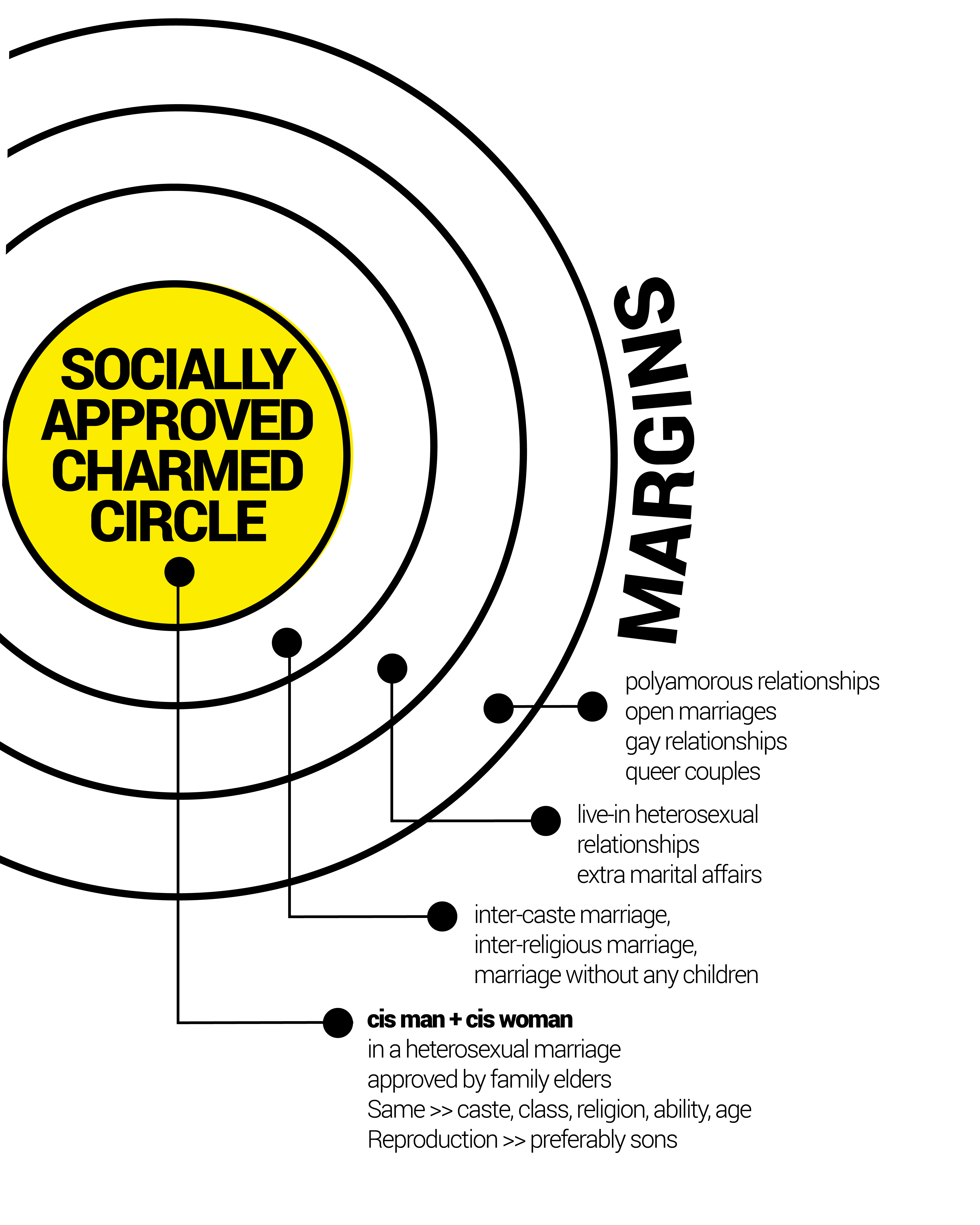

Sexuality, as commonly or popularly understood, has largely been defined in ways that fail to capture its diversity and entirety. The dominant social code of heteronormativity assumes and insists that heterosexuality is the only legitimate sexual orientation. Within this system, gender is constructed as a binary – male/female – with distinct, strictly enforced gender roles. However, people’s lives, identities and experiences are too varied and complex to be contained in such narrow boxes. We may be conditioned by our social institutions to aspire to a lifelong heterosexual marriage, defined by monogamy and procreation, but lived realities are testimony to such an ideal being little more than a carefully constructed myth. The mental health (MH) community has itself played a rather significant role in pathologizing non-heterosexual sexualities, rendering invalid the lives, identities and experiences of LGBTQIA+ communities, and upholding oppressive structures by providing “cures” for non-normative individuals, thus systematically pushing them further into the margins.

After Sec 377 of the Indian Penal Code was read down by the Supreme Court on 6 September, 2018, there was a spate of announcements about “queer-friendly mental health services to the LGBTQIA+ community”. The timing seemed odd. Decades of activism across the country had led to this historical moment. And Mental Health Practitioners (MHPs) had been working with queer clients for over a decade. While there is unquestionably a need for more services, the sudden widespread interest in the mental health and well-being of queer people right after the SC verdict seemed opportunistic, hence worrisome. It was in this context that MHI felt it necessary to interrogate and counter dominant approaches to sexuality in the mental health sector. As an MHI Advisory Board member, I approached some MHPs based in Mumbai, and a team of six emerged. We asked ourselves how we could generate and operationalize ways to make amends for the historical wrongdoings inflicted by the MH community upon LGBTQIA+ communities, and how we could now equip ourselves to be responsive to the particular needs of queer clients.

Why is it Crucial to be Queer Affirmative?

Is it enough to be queer-friendly while working with queer clients? Can “queer-friendly” convey the magnitude of what MHPs need to undertake in order to work with queer clients? Several of us, both within the team of six and outside, have been part of queer and feminist movements for decades. A queer feminist perspective joins the dots and shows us how our right to love challenges the growing right wing agenda to consolidate power by instilling in us fear of the “other”. Conservative controls applied to our bodies and feelings constrict the multiple and diverse expressions of our sexualities and genders. Does a merely queer friendly service take into account this relentless erasure and marginalization of LGBTQIA+ communities? Does it hold MHPs accountable for their complicity in our historical pathologization? Is it equipped to respond to the needs of queer clients by incorporating the issues and stressors inherent in living on the margins of a heterosexually defined world? The Queer Affirmative Counselling Practice (QACP) Course asked these and similar questions, focusing on ethical work with queer clients – work that includes: deconstructing, as MHPs, our own locations of power, privilege, and prejudice; educating our selves about queer lives; adopting an affirmative stance vs a neutral one; and advocating for the rights of all marginalized groups.

The mental health (MH) community has itself played a rather significant role in pathologizing non-heterosexual sexualities.

For too long in MH, queer sexuality had been considered through the lens of heterosexuality. This was an incomplete, incorrect and harmful gaze. No existing curriculum, course, trainings or materials represented the realities of LGBTQIA+ communities in valid or authentic ways. QACP was thus envisaged as an opportunity to reorient ourselves to an antioppressive therapeutic practice, and to reflect on why any work in mental health needs to be political.

Also read: Why Is The Mental Health Of Persons With Disabilities Overlooked?

Queer Affirmative Counselling Practice

We created a 6-day Certificate Course that covered perspective building so as to recognize inequalities and their impact on mental health, and also provided tools to address distress and promote well-being of LGBTQIA+ persons. These perspectives and tools support MHPs in modifying their ongoing practice to make it queer affirmative. The course was opened up to MHPs – psychotherapists, psychologists, psychiatrists, social workers, counselors, preferably with experience of working with queeridentified clients, or families of queer-identified individuals. Over the first six months, we conducted three rounds of training with 50 MHPs, in three major Indian cities (Mumbai, Bengaluru, New Delhi). Other cities and small towns are next.

Can “queer-friendly” convey the magnitude of what mental health practioners need to undertake in order to work with queer clients?

In the QACP Course, we challenged the idea of expert, objective, universal knowledge as being the only source of valid knowledge, and demonstrated the validity of experiential, situated, multiple knowledges. QACP draws on disability studies, user-survivor narratives, mad studies, histories of struggles, and queer feminist politics, to create ways to modify current MH practice. When applied, how does the queer affirmative lens help us rework diagnostic frameworks, protocols, and policies? What modifications may be required in our traditional approaches to clinical and counseling practice? How do we reframe notions of recovery and neuro-typicality so that we are responsive to a spectrum of experience?

QACP is not only about working with LGBTQIA+ communities and queer clients – it is an initiative that invites MHPs to reckon with the idea that in order to do ethical work they need to queer mental health practice overall. The QACP trainings are leading to the creation of a copyleft training manual for Queer Affirmative Counseling Practice that interested practitioners will be able to access free of charge.

Also read: Where Social Justice Meets Mental Health: How Does Caste Matter?

Politics of Responsibility

QACP reflects the politics of responsibility that we carry as queer feminist activists and MHPs. The lure of the pink rupee and the reading down of Section 377 saw many players entering the field of queer mental health with enthusiasm, but without an anti-oppressive framework or even any real understanding of our lived realities. Our own critical voices needed to be registered as part of the discourse. Our curriculum development process was an unprecedented phenomenon of sorts: with six queer-identified MHPs and trainers with different lived realities, strengths, and competencies, converging, brought together and supported by MHI, a funding agency that shares our values and politics. Words fail me in attempting to describe the organic synergy of this process as it unfolded.

Queer affirmative knowledge is knowledge generated by queer people – knowledge drawn from our lives, our politics, our struggles, and based on our lived realities and felt experiences.

Given that the edifice of QACP was based on shared politics and values, it followed that this foundation would inform our pedagogy. The methods of delivering QACP were participatory, experiential, feminist, and queer. In creating the curriculum, there were specific challenges that came from wanting to contextualize the knowledge we were producing. Most writing and research on queer theory and mental health has been produced in western countries with mainly white populations. Working with a constant awareness that an uncriticial transplanting of such knowledge would be of little benefit to MHPs or queer clients in the Indian context, we concentrated on building relevant content and frames of analysis.

Queer affirmative knowledge is knowledge generated by queer people – knowledge drawn from our lives, our politics, our struggles, and based on our lived realities and felt experiences. Committed as it is to countering dominant narratives of queer sexuality and gender, QACP foregrounds knowledge from the margins.

Shruti Chakravarty is the Chief Advisor of Mariwala Health Initiative. Her areas of engagement include mental health, gender, sexuality, and human rights. With 15 years of experience in the non-profit sector as a mental health practitioner, researcher, trainer, and social worker, she is currently a PhD scholar at Tata Institute Of Social Sciences (TISS), Mumbai, and has an independent therapy practice.

This article was first published in Mariwala Health Initiative’s (MHI) Journal ReFrame: Bridging the Care Gap. ReFrame is a journal that challenges existing norms and explores diverse voices within the mental health space. This year, the theme for ReFrame is ‘Bridge the Care Gap’ and through a compilation of articles of lived-experiences, from marginalised voices and based on alternative constructs to the Western-centric, bio-medical supply-demand equation of mental health care—we aim to we frame a comprehensive approach to mental health and social care needs that can be used to design interventions, services, support and advocacy.

Images Source: Mariwala Health Initiative