*Note: This is a non-exhaustive portrayal of the Indian economy as it stands today.

Five rupees. This is an approximate price for a pack of Parle biscuits, India’s largest biscuit producer. In mid-2019, Parle cautioned that they may let go of 10,000 workers due to significant decreases in demand, especially in rural areas.

Five rupees.

It’s easy to brush these figures off as inconsequential. Although, in combination with other factors, every datum can tell a story of what appears to be a clogged national economy.

The Agricultural Sector Ablaze

The second quarter of the financial year (July-September) churned a meagre 4.5% Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth rate. GDP growth rates can be measured by outputs, expenditure, and income. In India, contributions to GDP are determined by agriculture, industry, and service sectors at market prices. The formula for calculating GDP boils down to subtracting subsidies from indirect taxes and the GDP at factor costs.

Five rupees. This is an approximate price for a pack of Parle biscuits, India’s largest biscuit producer. In mid-2019, Parle cautioned that they may let go of 10,000 workers due to significant decreases in demand, especially in rural areas.

The fact that the latest reported GDP falls at a six-year low serves as a harbinger for India’s economic health. Weak growth signals impact business outlooks, investment, lending and borrowing patterns, and domestic consumption. The 4.5% figure is the first step to understanding the hesitation, especially on part of rural consumers, in spending on biscuits.

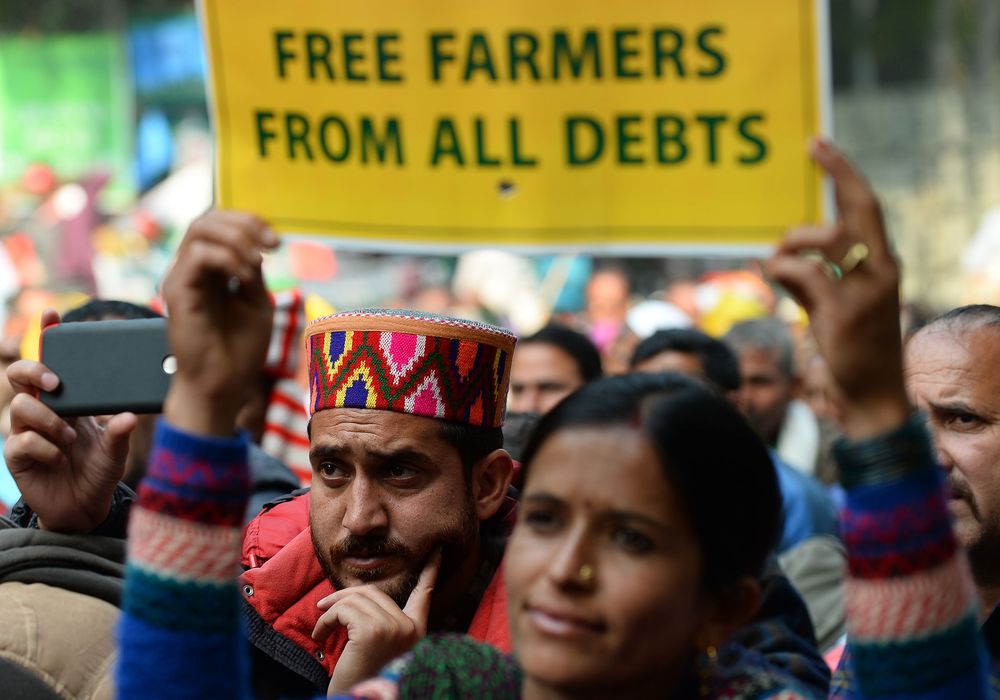

In October of 2019, protests by farmers across the nation went largely unnoticed. They collectivised to fight the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and demanded that agriculture be excluded from this economic pact. If applied to agriculture, this pact would decrease import duties on agricultural commodities to zero, seed companies would be afforded more rights to protect the intellectual property (IP) of their seeds, and foreign corporations could easily stop the government from providing subsidies with an international lawsuit. These provisions would enable countries to dump their agricultural products in India, make local farmer products less competitive, and make farmers vulnerable to criminalisation for using patented seeds. Many of these negative externalities already reign prominently in farmer’s livelihoods – to understand their desperation, look no further than farmer suicide incidents.

Over the last 5 years, spending on agriculture has fallen short of the budget. In combination with environmental vulnerabilities spurred by climate change, the government has managed to spend 17% less than the revised budgeted amount and has failed to deliver welfare to farmers. The urgency with which agriculture spending needs to be addressed comes down to numbers. Close to half of the Indian population, 600 million people, rely on agricultural outputs for their livelihood.

Suffice to say, limited government spending and regulation in the agricultural sector has contributed to a decline in rural consumer spending. A 2017-2018 survey conducted by the National Statistics Office (NSO) found that spending on food in rural areas decreased drastically – monthly spending decreased from 643 rupees in 2012 to 580 rupees in 2017. This pattern began in 2012 as farmer wages dipped, a slowdown occurred in the farming sector, and when unemployment rose in the non-farming sector. Given the figures listed above, these characteristics have been exacerbated today.

Broader Repercussions

According to data that has yet to be released, consumer spending in India dropped for the first time in over 40 years. Former Finance Minister Yashwant Sinha explains the chain of events when it comes to consumer spending – decreases in demand start in the rural sector, make their way into the informal sector, and eventually impact the industrial and corporate sectors. Coupled with a 6.1% employment rate, the highest in 45 years, disposable income and household expenditure will continue to decline. Unemployment is especially stark in India’s failing auto sector. A total of 350,000 auto workers have been laid off since April 2019 as car sales have declined by 36%.

Coupled with a 6.1% employment rate, the highest in 45 years, disposable income and household expenditure will continue to decline. Unemployment is especially stark in India’s failing auto sector. A total of 350,000 auto workers have been laid off since April 2019 as car sales have declined by 36%.

With the limited statistics presented here, the circuitous nature of consumer spending becomes abundantly clear. To stimulate demand, mitigate and address issues of climate change, and make food affordable for all, starting with the agricultural sector is key.

Following the demonetisation initiative (leading to a massive economic slowdown, hurting small businesses, and the inability to freely spend liquid cash), recent government initiatives include requiring foreign brands to source locally, cutting corporate taxes, purchasing more government vehicles (to revive the auto sector), guaranteeing a greater quantity of loans in security bundles to support housing lenders, and infusing public banks with capital. These quick-fix piecemeal solutions, such as buying more vehicles, will put out fires temporarily, but will do little to stimulate long term macro growth.

Another tactic the government has taken to integrate the various sectors of the economy is through digital banking. Digital banking is predicated on a vision to ensure a widespread provision of financial services to rural, urban, lower, middle and upper-class residents. Although, following demonetisation, small businesses who rely on digital banking face a great disadvantage if they reside in areas where the internet is frequently shut down. In Kashmir, where the internet has been shutdown for over four months, businesses are on a steep and rapid decline.

Also read: When Will Our ‘Achche Din’ Arrive, Ask Aggrieved Farmers At #KisanMuktiMarch

The Politics of Economics

Considering India’s economic reality, one would begin to question how we were not able to see these numbers beyond the clouds of communalism and divisive politics. However, economics is a highly political instrument that is fully integrated into Kashmir, CAA, and every major contemporary social and political issue. Each of these complex issues is a manifestation of the strains felt on our economy. The numbers aren’t simply present in charts and graphs for analysts – they tell the story of underreported farmer protests, of well-being in Kashmir, and of the hesitation to spend five rupees.

Featured Image Source: The Express Tribune