On 25 May, 2020, Derek Chauvin, a police officer in Minneapolis, killed George Floyd, a 46 year-old African American man. Chauvin placed his knee firmly on Floyd’s neck for 8 minutes and 46 seconds as he lay unarmed and handcuffed on the ground. As bystanders and witnesses pleaded with officers and video recorded the scene unfolding in front of them, in the background, Floyd repeatedly stated, “I can’t breathe” while slowly being murdered.

Rightfully so, the news of Floyd’s murder and the legacy of those before him (Breonna Taylor, Antwon rose Jr. Ahmaud Arbery, Freddie Gray, Michael Brown and countless others) sparked nationwide and worldwide protests against the prevalence of anti-blackness, police brutality and racial injustice. The Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement was reignited once more as record-breaking, diverse crowds gathered to demonstrate their outrage and exhaustion. As folks began mobilising, petitions, hashtags, social media campaigns, articles, and videos started circulating online.

People around the world were quick to show their support by sharing, liking and re-posting information in solidarity, particularly in India. There is no denying that remaining silent on an issue of this magnitude is itself a form of violence. There are also debates on whether there is a correct way to show solidarity. However, there is a convenient way to show solidarity, and for many, that comes in the form of a black square.

Rightfully so, news of Floyd’s murder and the legacy of those before him (Breonna Taylor, Antwon rose Jr. Ahmaud Arbery, Freddie Gray, Michael Brown, and countless others) sparked nationwide and worldwide protests against the prevalence of anti-blackness, police brutality and racial injustice. The Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement was reignited once more as record-breaking, diverse crowds gathered to demonstrate their outrage and exhaustion. As folks began mobilising, petitions, hashtags, social media campaigns, articles, and videos started circulating online.

#BlackOutTuesday

The social media campaign, #BlackOutTuesday was initiated by two black women in the music industry who demanded that the industry, who has profited enormously from black music, press pause on its activities on 2 June, 2020. What began as a black square attached to the hashtag #theshowmustbepaused quickly became a worldwide phenomenon shifting to #blacklivesmatter and #blackouttuesday. Unfortunately, the intentions of the campaign did not carry out, without consequences in practice. Mass black square posts crowded out important information for organizers and protesters. This crowding lasted beyond 2 June, as social media algorithms (which respond to the popularity of a post or hashtag) keep the squares locked in place.

On one hand, the black square allowed people to engage in political issues in a cyber or political context where doing so more vocally or publicly may be a dangerous endeavour. On the other hand, in the Indian context, most of the frustration came from people staying radio silent on issues close to home, and taking an explicit stand against racial injustice in the US. Rather than inspiring confidence, the contradictory nature of their posts shows that they are not willing to acknowledge the existence of racial injustices and violence happening right in front of them. To be clear, the frustration does not arise from levelling one injustice against another – in fact, this is a reductionist and futile task. The frustration arises in not understanding the contextuality and structural injustice of the anti-blackness, casteism and violence in India – it becomes evident that one does not understand the contextuality of parallel issues in the US.

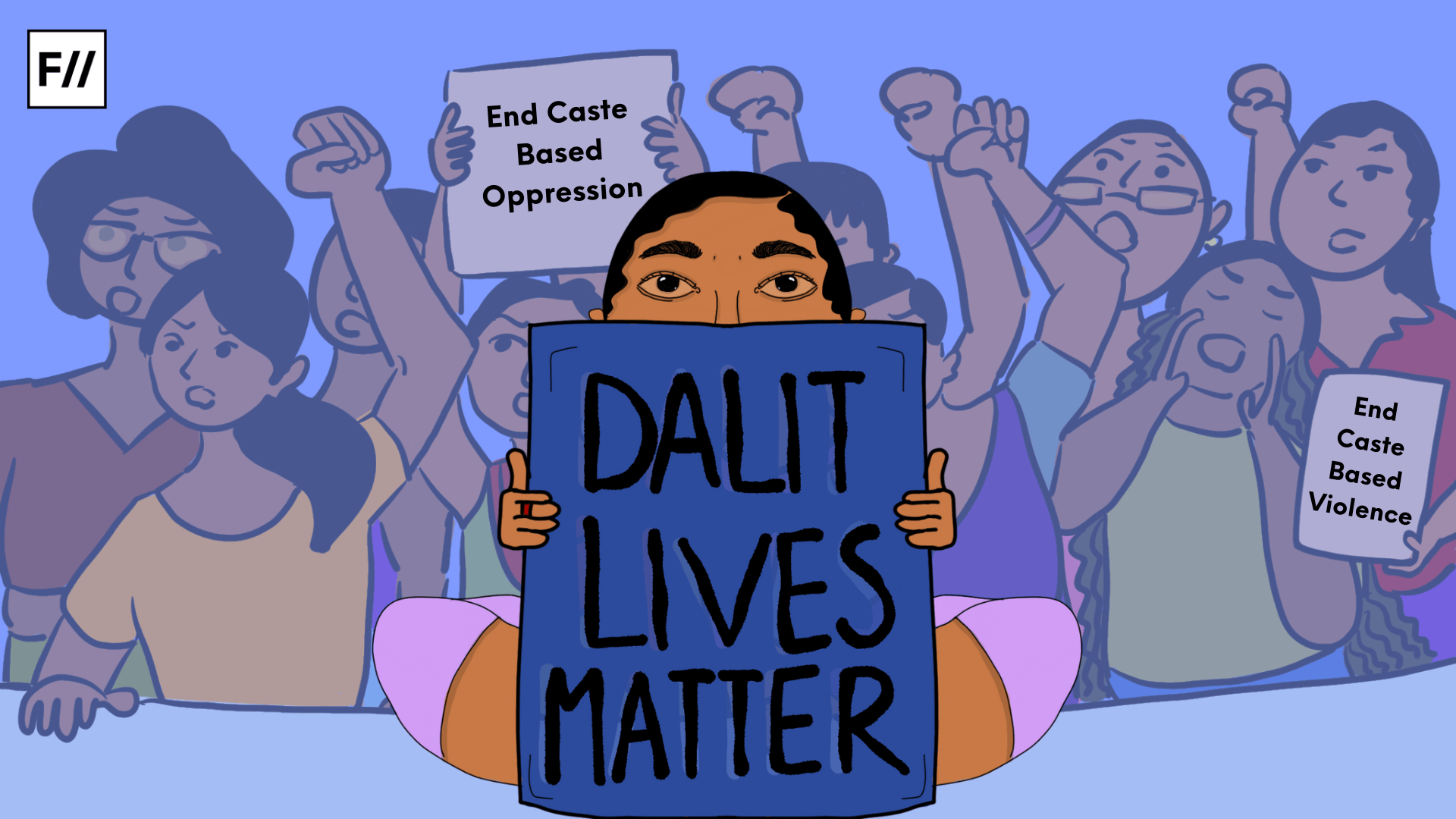

Dalit Feminist Perspective: Understanding Racial Injustice in India

It may be helpful to understand this frustration through a dalit feminist standpoint. This standpoint acknowledges the necessity for the experience and knowledge of dalit women to exist alongside the skills and resources of other groups who take it upon themselves to educate each other about the histories, social relations, and realities of marginalised groups. In tandem, transformative change is possible – not by speaking over or for Dalit feminists, but by unlearning and allowing yourself to embody dalit feminist perspectives.

Black populations, commonly referred to as Siddi people, have a long history and presence in South Asia – present day India and Pakistan. Their presence has repeatedly and systematically been erased from historical accounts, education, popular culture, and mainstream media – the erasure of their stories, their lives, and their struggles, much like in the US, is pervasive. In addition to being erased, overt and covert instances of anti-blackness towards Siddi people and non-resident black folks are underreported, widely dismissed, and often go unquestioned.

For the purposes of tackling racial injustice, if we look towards the anti-blackness and injustice in the US, we must take it upon ourselves to understand the gravity of it and see it wherever it exists. In line with a dalit feminist standpoint, this means visibilising histories and continuities of anti-blackness, casteism and systemic injustice in India so that we transform the system rather than succumb to it. Visibilising involves reversing negligence and avoiding tendencies to generalise contexts or groups of people, as both are forms of erasure.

Also read: Remembering Aretha Franklin: The Voice Of Black America

The Histories and Stories of Black Folks in India

Black populations, commonly referred to as Siddi people, have a long history and presence in South Asia – present day India and Pakistan. Their presence has repeatedly and systematically been erased from historical accounts, education, popular culture and mainstream media – the erasure of their stories, their lives, and their struggles, much like in the US, is pervasive. In addition to being erased, overt and covert instances of anti-blackness towards Siddi people and non-resident black folks are under-reported, widely dismissed, and often go unquestioned.

Whether it is cannibalism charges, stripping and beating women, or beating men to death, black folks feel unsafe in India; this is especially true for students in India of African descent. Even in cases where unruly mobs commit targeted attacks against African Student Association, figures in position of power, are hesitant to claim that these attacks are motivated by racial discrimination before investigations are completed. The subjugation of, and the violence committed against black bodies is intrinsic to South Asian history and predates the colonial era. Beyond overt violence, depictions of African people and South Asian’s appropriation of black culture is commonplace; ads and endorsements for skin lightening products are regularly broadcasted. Not only is there a pattern of suspicion, disgust and otherness directed towards black folks and black skin, but it is interrelated with the deep rooted legacy of casteism.

Casteism and Anti-Blackness

Of course, casteism and anti-blackness cannot be compared directly with one another – each phenomenon is nuanced. During slave trades, black people were told that they are lazy, stupid, and heathens; they were degraded and forced into exploitative labour. Caste is shrouded in seemingly religious ideologies by those in upper castes who claim authority and thereby designated dirty labour to lower caste individuals. In both cases, black people and those of a lower caste are denied basic rights. Discourse centered around othering, especially during the pre-colonial era, was exacerbated by colonial powers weaponisation of eugenics and race-science. As a system that distinguished between pure and polluted persons, the caste system fit well within the mould of institutionalised hierarchies.

While casteism and anti-blackness is deeply rooted in India’s history, it is a mistake to assume it no longer exists. The documented examples mentioned above demonstrate the continuation and persistence of anti-blackness. Black and dark skinned bodies are seen as barbarians, as poor people, and as Dalits (having worked for centuries in fields, many Dalits developed darker skin). While class and caste cannot be conflated, it is much more likely that this perception leads to intergenerational poverty being passed down. Anti-blackness is intertwined with casteism and continues to be seen as undesirable.

Roll Up Your Sleeves

It is abundantly clear that anti-blackness is not restricted to the US. Anti-blackness in India is a function of casteism and one of many manifestations of systemic xenophobia. Simply posting a black square is devoid of one’s willingness to get down in the ground and start digging up the roots of injustice. It’s important to recognise that overcrowding online spaces with empty words of support is misleading and is just as harmful as being silent.

Also read: Film Review: Girls Trip Rewrites Hollywood’s Portrayal Of Black Women

Before spreading awareness, or claiming to spread awareness, know how you yourself are complicit. Get uncomfortable, ask yourself hard questions, and see injustice for what it is – whether it is distant, or in your neighbourhood. Know your privilege and leverage it to stand up for others; a black square didn’t cut it today, and it certainly won’t be enough tomorrow.

Tasneem M. is a researcher based in Toronto.

Featured Image Source: WMBD