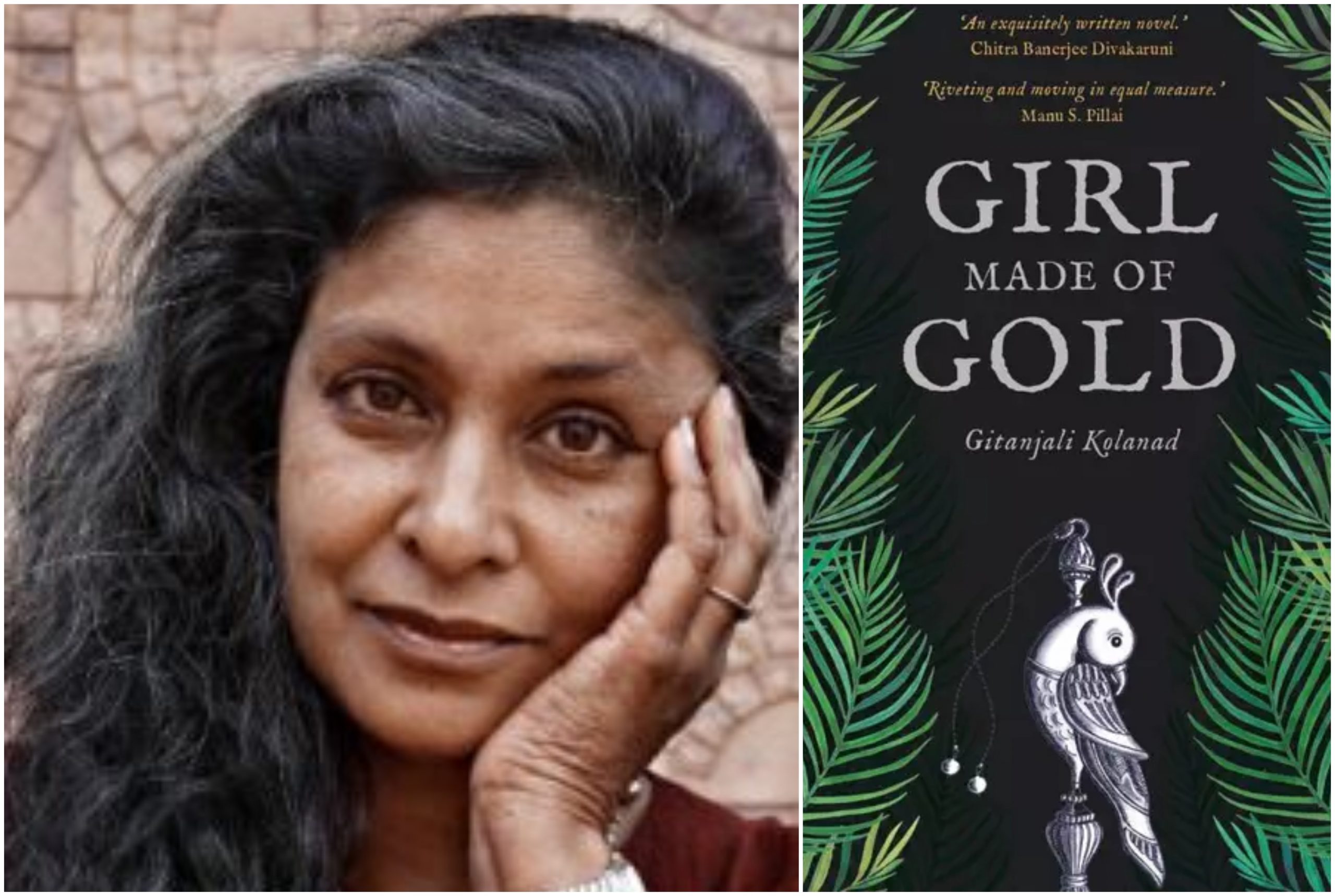

Set in the 1920s of the UNESCO’s world heritage site of the famous Chola temples, Thanjavur, in Tamil Nadu, Girl Made of Gold (Juggernaut, May 2020) is the first novel by the renowned Bharatanatyam dancer, writer and Kalarippayattu teacher, Gitanjali Kolanad.

Book: Girl Made of Gold

Author: Gitanjali Kolanad

Publisher: Juggernaut Books, 2020

A Girl Is Missing

Kanaka, a devadasi, is missing. She performs temple rituals, as usual. But one day, a priest and his limp nephew, Subbu, are waiting for her at the crack of the dawn; however, much to their bewilderment, Kanaka doesn’t arrive on time. It’s surprising for them as Kanaka was never late. Subbu is sent to the devadasi (matrilineal) house to wake Kanaka up and bring her to the temple, but no one knows her whereabouts. Nagaveni, the matriarch, orders people, but to no avail. However, upon learning nothing about Kanaka, the temple doors are opened, and there it is: a tiny, gold idol of a girl; a prepubescent girl maybe. And everyone shouts, “Kanaka!”

Told through its characters, which are many in this tiny volume—no, no one is telling their perspective—Girl Made of Gold is a peculiar tale of desire. There are multiple axes through which the story is told, but desire is the principle one.

Hence, it’s assumed upon priest’s announcement that Kanaka, the girl, has transformed into a statue. Subbu didn’t believe it. He was on his quest to find his love interest. Subbu’s mother, Brhadambal, tries to console him, but he remains inconsolable; he, in fact, accuses her chirpy behavior to be the cause that his father left both of them.

Contrary to what Subbu believed, his father left his household after mating with a devadasi. Justifying his act (leaving) by taking example of “others, great men, Buddha, Mahavira,” who left sleeping wives and children without saying a word, he did so, according to him, in a search, “to learn how to not do what [he] knew to be wrong, to act in opposition to what [he] desire.”

An Alchemy of Desire

Told through its characters, which are many in this tiny volume—no, no one is telling their perspective—Girl Made of Gold is a peculiar tale of desire. There are multiple axes through which the story is told, but desire is the principle one.

There’s Subbu, in need of Kanaka, his desires running wild for Kanaka reminiscing on the past and dreaming her naked daily. And Vallabedran, who was a patron of Nagaveni, also desired Kanaka. Nagaveni, who has mastered the art of seduction keeps it simple, “How do you keep a man wanting more? You make him wait. You say ‘not’ and then ‘yes’, ‘yes’ and then ‘no’.” She’s perfected love “as a science” by practicing, and in order to retain her patron didn’t mind when Vallabedran was attracted to Ratna. She’s never fooled into falling in love, as it’s not useful. What was useful was to keep Vallabedran, and influential people like him, visiting and monetarily supporting the matrilineal house. And it’s this reason that she’d have never minded if Vallabendran now wanted Kanaka, Ratna’s daughter.

But it’s not possible according to Ratna, who says this to Vallabendran, “She’s your daughter, you can’t just turn around and fuck her.” Valladendran never paid attention to this, listening to this he felt “an irritation with the world.” He wanted Kanaka, as “more and more often these days” Ratna’s skills were “useless” in bed. Given his position, “he was used to achieving the satisfaction of all his desires, and this was no different.”

Indra studied in London, and he was discriminated there because of his origins; not as a Brahmin, but because of being an Indian. He wonders, “Because a man has a black face and practices a different religion, that is reason enough for an Englishman to treat him as a brute?” This portion is deftly squeezed in the narrative in Girl Made Of Gold to show how a person in one system can be discriminated against in another system, for a similar argument can be extended to explain the exploitation of devadasis by his father, and others of his like.

However, blinded by his lust for Kanaka, he’s unaware of the fact that there’s a romance building up between his son, Indra, and Kanaka. But someone in his family knew about it: Indra’s grandmother. She is fond of talking to her grandson, who used to tell her about everything. She listened to him with utmost pleasure, as she desired him too, in a way. And upon finding Indra’s “dancing girl” to be different, she gives him, among many jewelry and artifacts, a diamond nose ring.

Like everything in the world, this secret was never to be kept forever. A frequenter to the matrilineal house learnt about the romance. It’s Janardana, Indra’s maternal uncle. It’s he who broke this news to Vallabendran, immediately repenting its consequences, which turned out to be really gory and disturbing. Janardana was never a typical man from the start: as a kid, he used to put ribbons in his hair; he never passed lewd remarks about the young girls; and “he learned ways of keeping his desires secret while revealing them too.”

It’s Ratna who told him if Vishnu can be transformed, then why not he? She’s amused by the fact that he has a hairless body, and immediately blurts that he’s not her type for she likes “rough dark hairy men,” precisely the kind that excites Janardana. She wore him a green sari, and asks him to take the round of the area in a sari, letting him fulfill his desires: being teased by men, being lusted for.

Also read: Book Review: The Far Field By Madhuri Vijay

The Great Divide

Indra studied in London, and he was discriminated there because of his origins; not as a Brahmin, but because of being an Indian. He wonders, “Because a man has a black face and practices a different religion, that is reason enough for an Englishman to treat him as a brute?” This portion is deftly squeezed in the narrative in Girl Made Of Gold to show how a person in one system can be discriminated against in another system, for a similar argument can be extended to explain the exploitation of devadasis by his father, and others of his like. But that’s how discrimination works. It’s useful for one party at the cost of the other. Back home, his father and his likes championed this art; and, in Britain, the Whites.

What was common between both of them? Hypocrisy.

It’s interesting when the object of disenchantment becomes an object of desire in a different setting, as all men of good caste were happy to keep distance with the “untouchable girls,” but at the same time didn’t mind raising their legs onto their shoulders. At this juncture, untouchability was never a barrier, as “in the privacy of their desire, they’d been equals.”

Such divisions were baffling for a foreign-educated child. He felt that there’s one code of conduct for his “mothers and sisters and wives, and quite another standard for the other kind of women.” He reflects that it’s not only in India, but in England, too. In a sense, this way, Indra is a man of modern sensibilities. Unlike his father, he’s attracted to Kanaka because of “her beauty and accomplishments, quick wit and playful, passionate nature,” which he thought were “natural and appropriate for a devadasi.”

But were these qualities good enough for becoming his wife? He was willing to reject such thoughts out of love for her.

With each turn of the page, this enthralling literary fiction keeps you on the edge. You’re constantly asking, ‘Who’s that person that the hunter on the first page found dead? How far did the romance of Indra and Kanaka go? Did Kanaka actually get transformed into a golden statue, the “dancing girl”?‘

Also read: Book Review: Invisible Women By Caroline Criado Perez

These are baffling question, which Kolanad reveals one by one, in a rich prose, keeping readers engrossed by using all storytelling devices: ‘river’s flow,’ ‘lion’s glance,’ ‘frog’s hop’ and ‘flower garland.’ And as a brilliant narrator, toward the end, she also comes “swiftly and precisely to the point, like a raptor sighting its prey, ‘flacon’s dive’.” And so do I. I hope that this book reaches many of us, and is widely read. It’s certainly the most important book interrogating a variety of desires, in a nuanced way, without taking any side; but telling a story, a narrative, in a hope that the “actions produce the results intended.”