Gulabo Sitabo, Shoojit Sircar’s latest release takes forward the director’s idea of feminism – an idea that had reached a point of compelling coagulation in Pink. Yet it is in the exploration of characters in Gulabo Sitabo that Sircar fleshes out female protagonists who, despite being thrown in an unequal world dictated by archaic gendered norms, manage to bend the rules controlling their lives. And that is the singular takeaway from the story – that there are innumerable brands of feminism as there are women; and no one-size-fits-all dictates the lives of women at large.

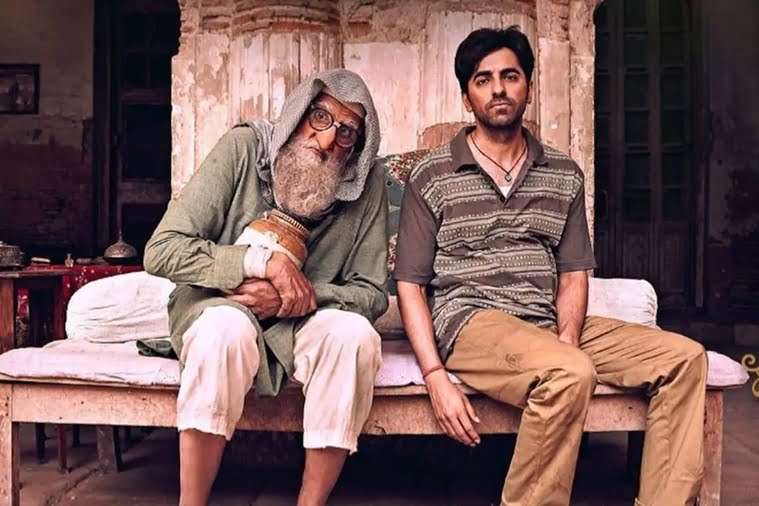

The storyline of Gulabo Sitabo is simple and straightforward. Mirza (played by Amitabh Bachchan) is married to Begum (Farrukh Jaffar), the owner of the decrepit, yet famed Fatima Mahal. He hopes to inherit the Fatima Mahal someday and with the nonagenarian Begum mostly keeping poor health, his hope seems robust.

On the other side of the story is Baankey (played by Ayushman Khurana) who is a second generation tenant of the Mahal. He is born in the Mahal, lives there with his widowed mother and three sisters. He runs a nondescript flour mill shop in the by-lanes of old Lucknow, feels a sense of ownership of the Mahal and like Mirza also dreams of inheriting it post the death of the ageing matriarch. Both men are wary of each other, try to steal a march on the other and attempt to inch closer to wielding ownership. In their attempts, they bring in a plethora of characters – a scheming archaeologist, a wily lawyer, a host of baffled tenants.

Mirza and Baankey are wary of each other, try to steal a march on the other and attempt to inch closer to wielding ownership. In their attempts, they bring in a plethora of characters – a scheming archaeologist, a wily lawyer, a host of baffled tenants.

However it is in the characterisations of Guddo (Bankey’s sister played by Srishti Shrivastava), and Begum that the film lands itself a winner.

Guddo and Begum represent two eras and class categories completely different in their situational demands and responses, just as their education, culture, and financial status. And yet, they are curiously united in their spunk, zest for life and unapologetic attitude. Together they garnish the storyline and add the saltiness, richness and spice.

Also read: Film Review: Portrait of A Lady On Fire – On Queer Love And Sexual Desire In A Patriarchal Society

Guddo has an education which gains edge with her inherent sass. She is clearly a better thinker than her dada Baankey and trips him up on sheer common sense and legal acumen. Plus, she reserves no regrets on her romps with a varied bunch of men and brooks no moralistic heartburn or seductive headiness afterwards. She looks at the tryst as a mundane activity, and reserves a thinly veiled disdain for the men who want her integrity without offering any of it to her. We see her pack off the man who raises objections to being “the third in the line…”. Likewise she is prepared to work for the lawyer and even bed the archaeologist so as to come out tops in the entire ownership game. She herself does not harbour any ambition to inherit Fatima Mahal, but is propelled by a certain sense of righteousness that is essentially provoked by the manipulative moves of Mirza.

Begum, on the other hand, is a woman of culture and sophistication – the tehzeeb and tameej – that her city Lucknow is so famous for. She is quite conscious of her class and cultural inheritance, as is evident in her constant reminders of her proximity to Nehru. Even her quarters and diurnal activities showcase this. However, she is wily, and hides a lascivious nature. She makes Mirza squirm with her questions as to whether they had eloped or whether they had had a proper nikaah. In the final rushes she just leaves with a former beau without a shred of regret or remorse. Even as Baankey says in complete befuddlement, “Bhag gayi, is umar mei?“, one cannot help but let out a whistle of approval.

Shoojit Sircar and Juhi Chaturvedi need to be applauded in their portrayal of these women. If the audience does not judge them, it is due to the non-judgmental, gender-sensitive and age-sensitive lens that the director-writer duo use. As the Mirza-Baankey squabble plays out, the audience itself becomes aware through the subtle nuances of theatrics and dialogue of who really hold the strings.

As the Mirza-Baankey squabble plays out, the audience itself becomes aware through the subtle nuances of theatrics and dialogue of who really hold the strings.

Strings…Puppets are made to dance to the tune of the puppeteer via the strings. Strings therefore symbolise control. Gulabo Sitabo are names of famous puppets in Lucknow; the squabbling duo of the wife and mistress who are finally controlled by the metaphorical strings of patriarchal norms. Sircar has chosen the names of the puppets to largely signify his protagonists except that he very intelligently leaves it to the audience to decide as to who really pulls the strings in this not-so-childish-game-of-ownership.

While the women are shown with sufficient agency without the requisite aggression, the male characters in the final rushes are caught in their own game of greed and deceit. From Mirza, to Bankey and even the archaeologist who is emasculated by a single “Agli baar dental kara lena” advice by Guddo, each man here is out-maneuvered by the machinations of the women.

Begum and Guddo stand out – but so does Fauziya, Baankey’s girlfriend who refuses to take a wimp of a man who pins his hopes of growth on the death of an ageing woman and does little else to change his state. She sleeps with him and gets dropped back home and does not take any delight in his martyrdom. She is a go-getter and views marriage as inevitable and therefore tries to leverage her chances within this as much as is possible. Her primary reason for choosing Baankey is not the ministrations of the heart, rather in his being part of Fatima Mahal. Ultimately, she makes her choice and leaves Baankey to marry a man whose materialistic achievements outstrip his. However, she does come back to show her worth to Baankey and her comment on his inability to identify ‘multigrain flour’ makes a pointed point of him being a loser.

Sircar’s women characters are no paragons of patriarchal virtues. They are women of the real world, made of flesh and blood; desires and compulsions. Provoked by their circumstances, they make the best out of their situations and therein lies their strength. Sircar refuses to load them with moral compulsions neither in body, nor mind. He is content to let them be women of substance.

Also read: Piku Review: 13 Things We Liked About Piku

Finally, there is the other protagonist – Fatima Mahal which is as real a character as the others. The Mahal forms the backdrop of the negotiations of the myriad characters and is a looming symbol of the feminine. History has been awash with instances where conflicts and wars have been fought over women. Men have always laid claim over the women, especially their sexuality; never bothering to ask them of their own wishes. Whenever the women have spoken up and acted on their free will, they have been subjected to horrific assaults, all legitimised and justified. Bodies and souls have been riddled with the assaults of men, each wanting ownership, each believing in their right to do so. Fatima Mahal is the metaphorical subject of lust, greed and ownership. Bankey thinks nothing of kicking her insides (the latrine wall) in his claim over her, as also Mirza who schemes to own her and lets in other men who size her up and attempt to rein her in with their lust-filled manoeuvres. It is finally a woman – Begum, who steps in to put an end to this sordid drama. Fatima Mahal does not get its mukti through the hands of a man. Sircar seems to know that men lack the moral authority and cognitive prowess to release women from their chains and that shows in the final shots of the movie.

If Pink earned Shoojit Sircar the badge of being a feminist filmmaker, Gulabo Sitabo will see him enter into the intellectual ambit of the feminist discourse. For once we cut free of the stereotype that only way to portray a woman as feminist is through the archetypal ‘modern woman’ narrative – dressed to play the part, open to smoking, drinking and swearing.

Also read: A Feminist Reading Of ‘Pink’

Featured Image Source: Stills from the movie