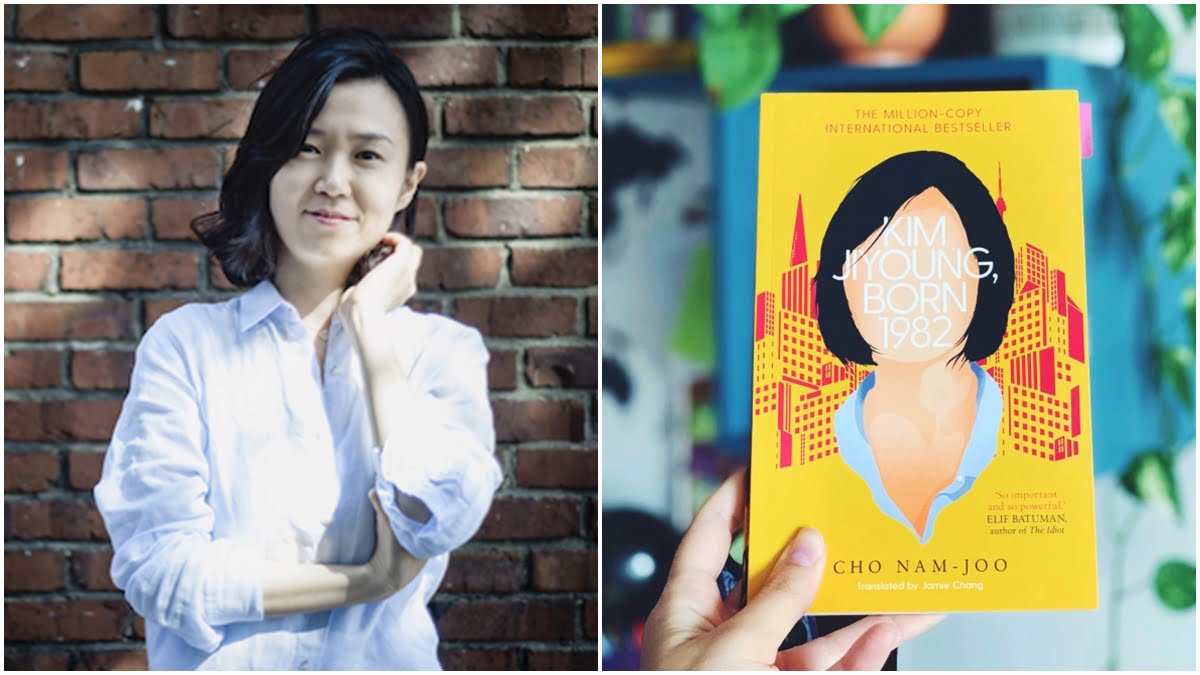

Cho Nam-Joo’s Kim Jiyoung, Born 1982 has been called “the South Korean #MeToo bestseller“. Published in Korean in 2016 when the #MeToo movement was relatively recent, it was translated into English by Jamie Chang in 2020, as #MeToo, no longer new, continues to yield stories that show the structural nature of sexism. This novel is a timely read as we strive to find ways for women to have healthy and meaningful lives in a deeply depraved society. Kim Jiyoung, Born 1982 is a strange novel. Its strangeness, however, comes from the commonplace nature of the story it has to tell – that of sexism and misogyny so unspectacular that we sometimes forget to question them.

It is fairly easy to summarise what Kim Jiyoung, Born 1982 is about: the psychiatric case study of a woman who has dissociative disorder whereby she “becomes” other women from time-to-time. There is nothing remarkable about Jiyoung’s story. Instances of misogyny such as, sex-selective abortion, preferential treatment of the male sibling, uniform policing of female students, leaving one’s job to raise children, resonate beyond the novel’s uniquely Korean context. These are such common experiences for women across cultures, that their unjustness has been overwritten by their apparent naturalness. Even Jiyoung’s fate is common to that of many women – diagnosed with an illness that requires psychiatric treatment. This quotidian narrative forces us to ask: is it possible for women to stay sane in a world that depends on their insanity?

Also read: Book Review: Women And Sabarimala By Sinu Joseph

Born in 1982, Kim Jiyoung is the second of three children, two girls and one boy. From time-to-time, she “truly, flawlessly, completely” becomes other women she knows – her mother, her college friend who died in childbirth, and other women, some living, some dead, “all of them women she knew“. We follow her life from childhood to motherhood. Coming into existence because her mother wanted a son, Jiyoung goes through life registering that things around her are normal but perhaps should not be.

As a child, when she is harassed by her male classmate, her teacher tells her “Boys are like that…They’re meaner to the girls they like.” Jiyoung is completely baffled by this as she knows that “If you like someone, you’re friendlier and nicer to them.” Much like a girl growing up in India, Jiyoung hears all around her how much more dependable, mature, and smarter girls are. Even though boys are less mature, less detailed in their work, and less smart, they inevitably have a greater share of power, even in primary school as “there [are] definitely more boy class monitors.”

This is a crucial lesson for girls to learn. As we see here, this is a dynamic that is everywhere: at home, where the grandmother gives Jiyoung’s brother the better portion of everything; at school, where skirts must cover knees and not be too tight but trousers can be any length and elasticity; at university, where men are always especially recommended for internships even though women are better students; in the workplace, where men are eased into their workload so they last longer at their job whereas women are frontloaded with more work since they will leave in a few years anyway to tend to their home and children; and, in her marriage, where Jiyoung must quit her job to give birth and raise their daughter while her husband remains unaffected. Kim Jiyoung’s entire life revolves around knowing the relegation of her place and not questioning it.

The key lesson that Jiyoung learns here is that women’s problems are endemic in society but to point them out is not to identify the problem itself but to identify oneself as the problem. As the high-achieving student, who is passed over for her less-deserving male classmates for an internship, is told when she questions this choice: “Companies find smart women taxing. Like now – you’re being very taxing, you know?”

As a result, Jiyoung is silent and passive, so much so that her life and thoughts are mediated through the report of her male psychiatrist. Her silence is, however, undergird by her realisation that her circumstances, despite being the norm, is deeply unfair. Even more painful is her awareness of the false myth of female exception – the belief that though women around her fail to succeed at their careers and their conjugal lives simultaneously, with the right amount of hard work and perseverance, she will rise to be the perfect woman in a man’s world. The narration of her life is rooted in facts, peppered with citations of news and government reports.

Jiyoung’s story is that of every woman. She becomes the women she knows and in the process. the women she knows become her. Their lives converge and seep into each others’ as they become statistics for policy and legislative reforms that projects the promise of better lives for women, but without taking into account that changing a cog in a machine makes the machine more efficient, not different.

Also read: Book Review: Conjugality Unbound By Srimati Basu And Lucinda Ramberg

Even Jiyoung’s supportive husband cannot help her. She becomes a “stay-at-home parent” as her husband’s job is more stable, pays better, and because it is more common for husbands to work as women stay within the households. Also a part of this bargain is the unpaid domestic labour which “Some demeaned…,while others glorified…, but none tried to calculate its monetary value. Probably because the moment you put a price on something, someone has to pay.” Jiyoung becomes a different woman for the first time after she overhears a few men call her “mom-roach” as she drinks coffee on a park bench with her daughter in a stroller. She becomes other women upon realising that the society registers her (and women like her) as vermin even as she has given up her job, her life, and her dreams, to reproduce (for) it.

Kim Jiyoung, Born 1982 is a simple, straightforward, and a slim encapsulation of a woman’s life. Its tone, style, and even its size point at its commonplace, oft-repeated, and well-known story. There is something compelling in seeing the representation of this narrative of women’s systemic devastation as completely unremarkable. This novel led to a crowd funding campaign for a book called Kim Ji-hoon, Born 1990 to tell the tale of reverse sexism faced by men in Korea. What is ironical about such claims is that they do not deny the plight of women like Jiyoung, but only affirm it by showing that not just women but also men face it. This is precisely the point that this novel makes. We must all read Kim Jiyoung, Born 1982 not to find Jiyoung in its pages, but to find ourselves.

Meghna Sapui is a PhD student in English at the University of Florida. She works on nineteenth century colonial literatures and teaches feminism and literature to undergraduates. She can be found on Twitter.

Featured Image Source: Erna Writes