Criminal law in the present form, excludes certain interests, perspectives and also experiences of women on a large scale. This is done fundamentally through the dichotomy of public-private divide and the incorporation of the patriarchal interests. Exclusion of women and emphasis patriarchal values is the main focus of the feminists who critique the legal system, especially the criminal laws.

Exclusion of women and emphasis patriarchal values is the main focus of the feminists who critique the legal system, especially the criminal laws.

Decriminalization Of Adultery

The adultery law that existed for a hundred and fifty-eight years did not take into consideration the will of the woman, unlike the sexual assault laws in India. A woman would not be punished under the said provision for adultery under the Indian Penal Code but the man could be prosecuted for having sexual intercourse with another man’s wife, even in the case of the act taking place with the woman’s will. A petition was filed in the Supreme Court demanding the provision to be struck down. The five-judge bench in the said case held that the provision as “archaic, arbitrary and unconstitutional.” The bench observed that the provision did not treat women as equals with men and that a husband is definitely not a master of his wife. Women over such a long period have been treated unequally and perceived as objects controlled by men.

Also read: Marital Rape: Why Are Indian Laws Still Confused About This?

Sexual Violence And The Law

The critique of these criminal laws can be viewed as two-fold. Prior to 2013, only penis penetration of the vagina was constituted as rape according to Section 375 of the Indian Penal Code. Object penetration or penetration by the use of fingers did not constitute to be rape and hence, prescribed a lesser punishment. The rational for this distinction in the criminal laws, as can be observed, is its patriarchal motive. Since penal penetration could lead to pregnancies, the patrilineal property rights were seen as threatened.

The second patriarchal aspect of these criminal laws continues to exist even after 2013. This aspect lies in “consensual sex given on the false promise of marriage constitutes rape.” The courts have granted convictions at times, but the judiciary has more often than not ruled against the complainant, rather than the accused. The assumption made in order to acquit the accused in such cases under the criminal laws is that a ‘good’ woman would not have consented to sexual intercourse prior to being married. Invocation of this very provision in itself is problematic irrespective of a conviction or an acquittal as it is a patriarchal and sexist provision. Further, in August 2019, the Supreme Court clarified that unless the false promise is proven, sex between two consenting adults founded in the promise of marriage, will not be considered as rape. An article in the Bar And Bench further explained why bringing “consensual sex given on the false promise of marriage” under section 375 will be a “great disservice” to the actual rape victims.

The problems with the rape laws that existed in India under criminal laws are quite evident and can be seen through in the Justice Verma Committee that was formed post the Delhi gang rape case of 2012. This called for various steps to be taken immediately that included a visionary report, a new law on sexual harassment at the workplace and also an amendment to the Indian Penal Code. Feminists also criticise the raise that has been made in the age of consent by the POCSO Act, 2012 to 18 years as it criminalises juvenile sexuality and acts as a reflection of patriarchal values that are vested in such criminal laws. It can be inferred that the law by itself cannot provide for feminist justice.

It can be observed that there exist major differences in the Criminal Law Amendment Act, 2013 when compared to the recommendations made by the Justice Verma Committee Report. The amendment to the Act does not recognise the existence of rape in an ongoing marriage and also did not consider the Committee’s suggestion to amend the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act in such a way that no sanction is now needed for prosecuting an armed force personnel accused of a crime against a woman. Neither does it consider gender neutrality for both the perpetrator, who is assumed to be male and for the victim, who is assumed to be a female. Although the definition of rape has been expanded, the punishments are not classified in accordance to severity.

It was only in July 2016 that the Supreme Court ruled to end the impunity of the armed forces to keep a check on the excessive use of force beyond the call of duty, reported The Hindu.

Also read: The Law’s Differential Treatment Of Men And Women’s Voluntary Intoxication

Marital Rape

In all cases of separation (be it informal separation or through a judicial order), marital rape has been criminalised. The sentence for the same has also been significantly increased but the fact remains that within a continuing marriage, marital rape is yet to be criminalised even through the amendment to the Act. The need for the consent of a married woman to be taken by the husband is not considered important according to the amended Act and hence, portrays a married woman as an object used by the husband for the purposes of sex.

The concrete legislation should provide for a better understanding of the severity of the crime perpetrated and infuse certain amount of sensitivity about criminal laws amongst the citizens.

A concrete legislation against criminal laws covering sexual harassment is required in our country and the 2013 amendment is a progressive step towards it, in spite of the flaws. The concrete legislation should provide for a better understanding of the severity of the crime perpetrated and infuse certain amount of sensitivity about criminal laws amongst the citizens. The executives should be encouraged to implement these laws while keeping the spirit of the legislation in mind – to bring justice to the victim. Only then is it possible to award deterrent punishment to crimes against women.

Simranjyot Kaur is a recent graduate of National Law School of India University, Bangalore. She is highly interested in studying intersectional material concerning women and Dalit community in particular. Currently, she is checking off things to do from the quintessential lockdown list of reading, writing, gymming and binge watching. She can be found on Instagram.

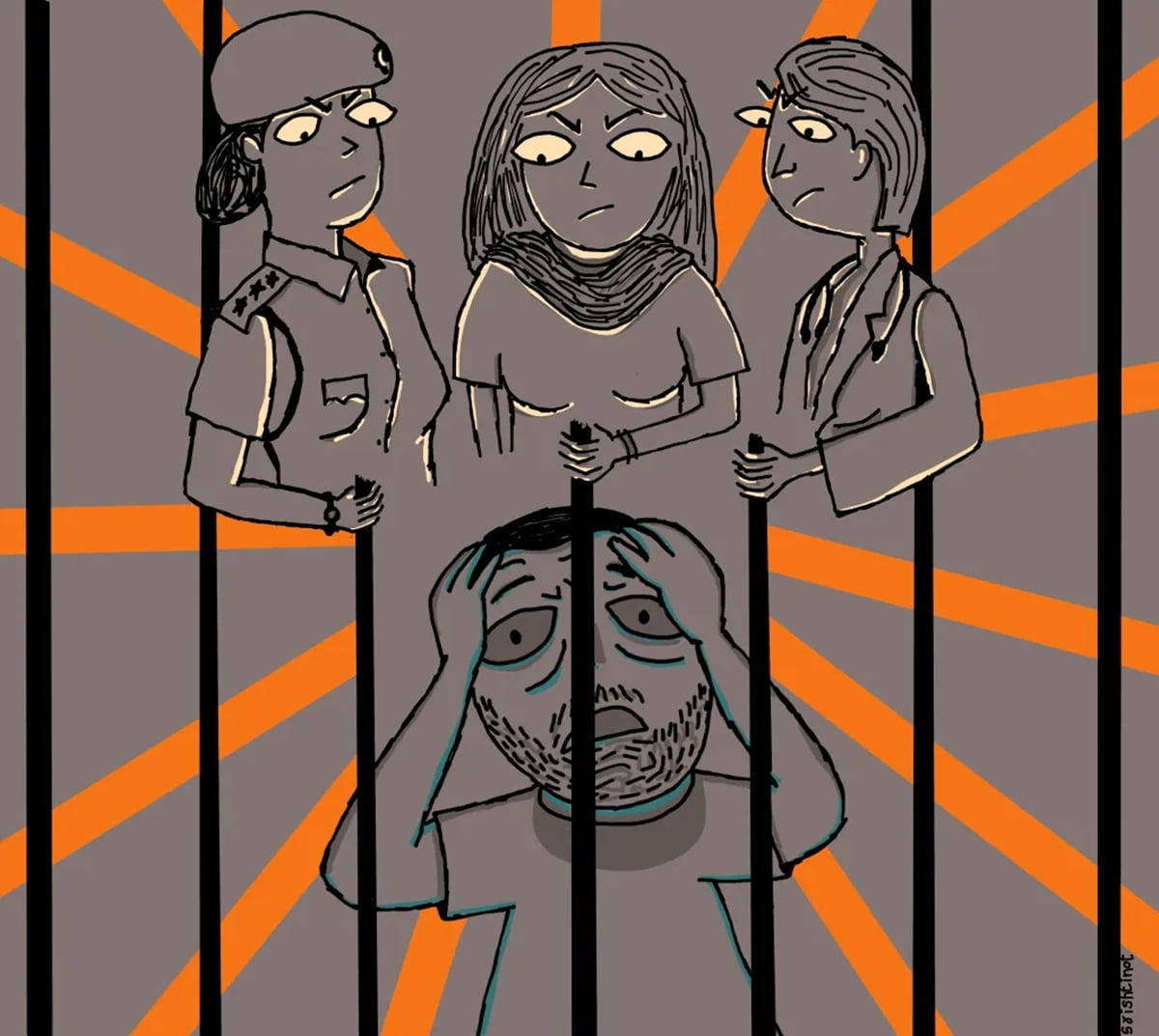

Featured Image Source: Srishti Sharma/Feminism in India

Why don’t we give feminist the right to make our law more equal and better. They sure would do a much better job.