When we think of the early Indian society, our imagination drifts towards the history books we read as kids. We think of the Magadha Empire, the glorious monuments—a country rich in literature, jewels and culture. We wear our history proudly on our chests, wrists and forehead. We brag about it in front of foreigners and expect every person we encounter to feel the same way. However, while we do take pride in our history, our consciousness naturally suppresses the unpleasant part of this vibrant past.

While it is a fact that India was one of the earliest societies to flourish, it is also a fact that there is no one yardstick to measure a well-developed society. Even though the word ‘development’ isn’t the most ideal way to describe a society, it is all we have for now. If monuments and governance are important elements of a society then so are the living conditions of its people.

In order to gain a holistic understanding of a society, it is important that we look at the lives of the ordinary people. More importantly the ones we don’t hear of, in the garb of stories of greatness. They are conveniently erased from our history books, and their worth rendered useless in front of a flourishing economy and strong administration.

While it is a fact that India was one of the earliest societies to flourish, it is also a fact that there is no one yardstick to measure a well-developed society. Even though the word ‘development’ isn’t the most ideal way to describe a society, it is all we have for now. If monuments and governance are important elements of a society then so are the living conditions of its people.

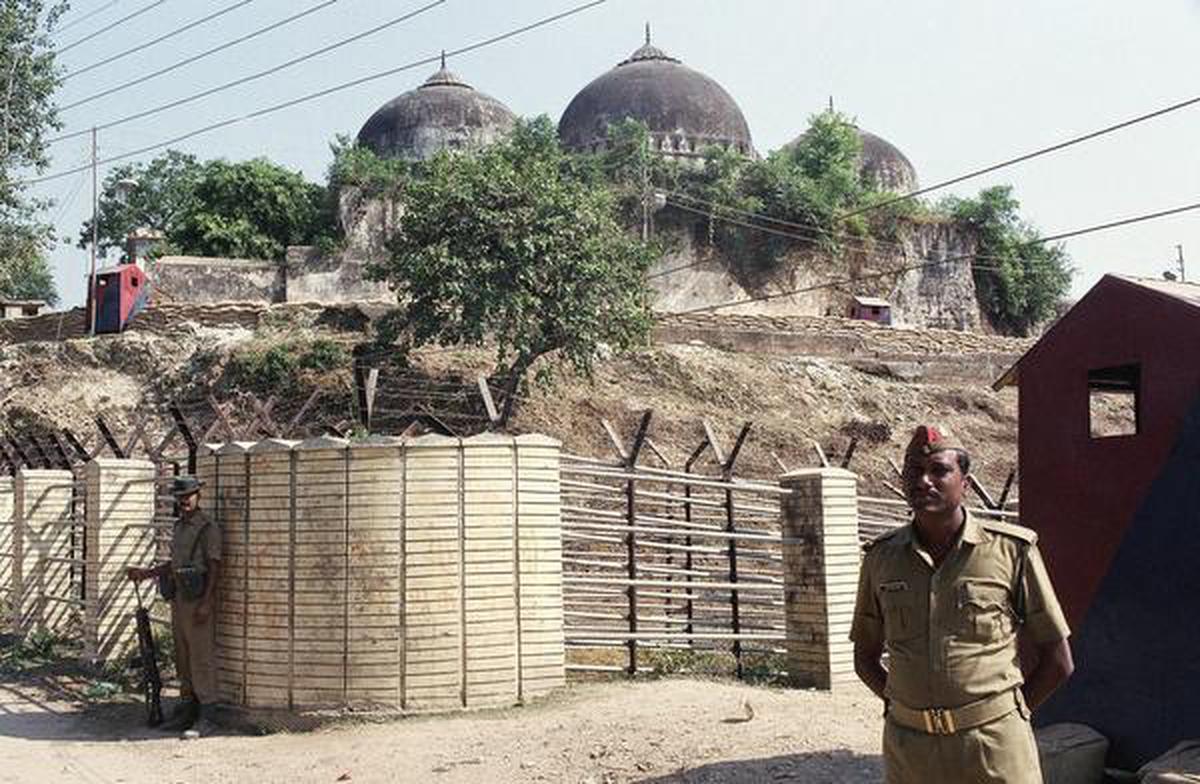

The Brahmanical Hindu Society

Early India was characterised by its heavy importance towards land and religion. Women and property were often linked together in celebrated Hindu epics and thus women were traded similarly. They were not allowed to accumulate large sums of money and stridhana too was limited to marriage often given in the form of jewels, ornaments and presents functioning as the sole source of finances.

Remarriage was strictly prohibited and practices such as sati were acceptable and encouraged. While upper caste women still enjoyed certain level of dignity, women from the “lower” varnas were severely exploited. According to Manusmriti, a Brahman, Kshatriya, or Vaishya man can sexually exploit any shudra woman. Even the killing of a dalit woman is explicitly justified as a ‘minor offence’ for the Brahmins: equal to the killing of an animal (Manusmitri).

Such was the state of the early Hindu society.

Also read: How Are The Recent Farmers’ Protests In India A Feminist Issue?

Brahmanical Patriarchy And Modern India

One might think that it is futile to discuss this history since India has moved far away from its roots but they will find themselves mistaken. In 2018, Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey received strong backlash after a photo of him holding a placard ‘Smash Bahmanical Patriarchy’ hit social media. The photo sent multiple groups into rage, some defining it as ‘hate speech’ while others calling it an attempt to “malign a community”.

So, what is Brahmanical Patriarchy?

In 1993, Uma Chakravarti coined the phrase Brahmanical Patriarchy. According to Chakravarti, social organisation in India consists largely of a “closed structure to preserve land, women, and ritual quality within it.” She explores the twin relationship between caste and gender discrimination as she points out that, “The purity of women has a centrality in brahmanical patriarchy, as we shall see, because the purity of caste is contingent upon it.”

The Brahmanical code of guarding female sexuality transcends beyond gender oppression. It links to a larger structure of caste hierarchy and resource accumulation. Chakravarti writes, “The lower caste male whose sexuality is a threat to-upper caste purity has to be institutionally prevented from having sexual access to women of the higher castes so women must be carefully guarded.“

In present India, this manifests as honour killings against those involved in inter-caste marriages. In an article Reuters reports that Evidence, a Dalit organisation, has recorded 187 cases of caste-based killings in Tamil Nadu between 2012 and 2017. On further investigation, we find that Dalit women as compared to “upper” caste women are more vulnerable and at a higher risk to violence.

As Human Rights Watch was told by a government investigator in Tamil Nadu, “[n]o one practices untouchability when it comes to sex.” According to Dalit activists, Dalit girls have been forced to have sex with the village landlord. In rural areas, “women are induced into prostitution (Devadasi system)…which [is] forced on them in the name of religion.” Rape too is a common phenomenon in rural as well as urban areas. According to Dalit activists, Dalit girls have been forced to have sex with the village landlord.

The Brahmanical law of excluding Dalit women from accessing education still affects a large majority of Dalit girls today. According to the National Commission for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes 2000, approximately 75% of the Dalit girls drop out of primary school. This early drop-out is often a result of poverty, bullying and isolation by classmates and even teachers.

While political parties have often promised welfare programmes and “upliftment” of marginalised groups, poor execution and corruption leaves these promises unfulfilled. Even feminist movements such as #Metoo failed to accommodate Dalit experiences and were eventually hijacked by savarna feminists. However, despite this constant exclusion, anti-caste voices continue to grow stronger in India. Dalit feminism continues to tackle the intersection of caste, class and gender by resisting against these hegemonic systems.

It is no news that state institutions like police and judiciary fail miserably at addressing gender based violence. When layered with caste, these systems reveal their own prejudices and desire of maintaining the status quo. Brahmanical Patriarchy in modern India affects women as deeply as it did in the early Hindu society. While Indian democracy does guarantee basic rights to women, the outdated laws and dysfunctional state systems do little for bringing the required change. Women who enjoy caste privilege might be quick to dismiss Brahmanical Patriarchy but a closer introspection of their individual choices, prejudices and perceptions of marginalised groups around them can reveal the truth. As an upper caste individual, I realised my privilege and the various socio-political dynamics I safely manage to escape.

The “modern” Indian society needs a re-examination, from its very origins. Perhaps, our glorious history isn’t that glorious after all. Our favourite mythological shows might be grand but they are also embedded in politics and appeasement of its majoritarian upper class, upper caste viewers. Our seemingly harmless language is full of slurs and prejudices that we fail to notice. Our news channels, films and social media may represent the ideal word, but it is important to remember that the world too is merely a reflection of what we want to see.

So, the next time we talk about dismantling patriarchy and equality, it is important we make sure the mic is in the right hands.

Also read: Growing Up In An Interfaith Family: How Are Interfaith Relationships Perceived…