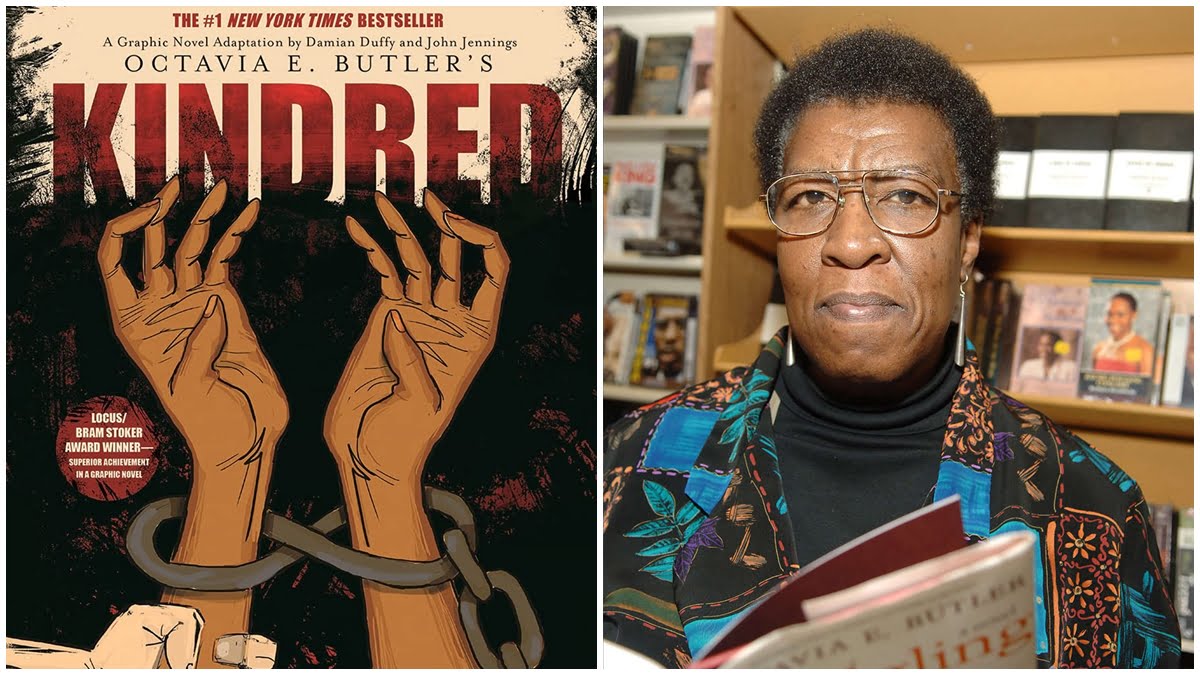

Octavia Butler minces no words or time in plunging the reader into the deep end. Kindred is about Dana, a 26-year old writer in 1976 California who suddenly finds herself transported to 1818 Maryland, beckoned there by an ancestor, Rufus. Every time Rufus is in fatal danger, he conjures Dana from his future, not very conveniently for either, as it happens. Dana is transported back to 1976 only when her own life is in danger. Time functions differently in the past. A few minutes in 1976 translates to months in 1818 and a few days to years.

Published in 1979, Kindred was groundbreaking for its time. It would be wrong to characterize Kindred as solely a work of science fiction. It is, in the ultimate analysis, a lesson on historical social justice. The language is easy flowing and minimalistic, and Butler describes rather than pontificates, crafting for us an unputdownable book. Butler uses time travel to demystify gender and race relations. More importantly, the book raises important questions that are relevant for the contemporary Indian context as well.

Published in 1979, Kindred was groundbreaking for its time. It would be wrong to characterize Kindred as solely a work of science fiction. It is, in the ultimate analysis, a lesson on historical social justice. The language is easy flowing and minimalistic, and Butler describes rather than pontificates, crafting for us an unputdownable book. Butler uses time travel to demystify gender and race relations. More importantly, the book raises important questions that are relevant for the contemporary Indian context as well.

Also read: Book Review | Mobile Girls Koottam: Working Women Speak by Madhumita Dutta

Time travel to 1976 and to 1818

The suddenness with which Dana is catapulted into a different time does not spare the reader either. Reading Kindred in 2022 had me travel twice in time. First, to 1818 Maryland along with Dana and second, to 1976 California where Dana was from. The idea of a black woman being stuck, with no hope of return, in a slave state in the early 1800s America, gave me a visceral fear.

Blacks here were assumed to be slaves unless they could prove they were free – unless they had their free papers. Paperless blacks were fair game for any white. (p.30)

This ‘paperlessness’ of racism describes, through material concerns, the precarity that racial injustice produces. It also gives us an understanding of the panic that consumes Dana and the imperative to problem-solve at every instant. This breathless urgency is sustained throughout the novel only waning whenever she moves back to 1976, when the narrative goes into a comparative lull.

In her third lapse into the 19th century, Dana is accompanied by her husband, Kevin. While they settle into a precarious life, held aloft by deception, she observes with surprise how easily Kevin and she had acclimatize to the times. At this stage, neither of them is completely immersed in the time travel experience. They are both whiling away their time and waiting to get back to 1976. Interestingly, when their sojourn together is broken, both of them lose touch with their 1976 reality.

Then I realized that I wasn’t really dizzy – only confused. My memory of a field hand being whipped suddenly seemed to have no place here with me at home. (p.124)

In many ways, Kevin was a timebound anchor for Dana and vice versa. And soon this confusion is transformed into the past becoming a greater reality than 1976.

I felt as though I were losing my place here in my own time. Rufus’s time was a sharper, stronger reality. The work was harder, the smells and tastes were stronger, the danger was greater, the pain was worse . . . Rufus’s time demanded things of me that had never been demanded before, and it could easily kill me if I did not meet its demands. That was a stark, powerful reality that the gentle conveniences and luxuries of this house, of now, could not touch. (p. 211)

Butler brings alive the heightened senses that suffering induces and that overwhelms every other experience in life.

In one of her 1976 interludes, Dana looks up books on the antebellum south to help her make sense of what is happening. But the books that come close to explaining are the ones about World War II and the Nazi treatment of Jews. In fact, Dana has the urge to explain slavery with the help of many contemporary and historical examples. At one point, she observes that South African apartheid comes closest to 19th century slavery.

More interesting for the Indian reader in 2022 is the time travel that we are forced to do to 1976. Barely 10 years since the civil rights movement, when race passions were at a height, one cannot but imagine 19th century slavery within the context of mid 20th century racism. We are presented with important vignettes from Dana’s own life experiences, those of her mother’s and her aunt’s and uncle’s to give us a perspective on racism in the seventies and before.

Relationships

The most interesting relationship is the one between Dana and Rufus. Disgust, hatred, combined with the need to protect him to save her own existence characterize the first few interactions. Dana is older and Rufus is a young boy, so there are instructive moments when Dana tries really hard to make Rufus slightly more sensitive to black lives. But the age difference inverts towards the end of the novel, stealing from her any semblance of authority she had earlier felt.

I could accept him as my ancestor, my younger brother, my friend, but not as my master, and not as my lover. (p. 291)

Another relationship is the one between Kevin and Dana. Kevin forms an anchor, but he is also the one who takes the brunt of Dana’s frustrations. Any kind of time travel is bound to strain any relationship. But if one considers that the lived precarity that Dana experiences in the antebellum south is something Kevin, a white man from 1976, can never expect to experience in the same time zone, the pressures on the relationship are unimaginably heightened.

The relationship between Rufus and Alice is another fascinating reveal. Dana realizes that the relationship between her black female ancestor and the white male ancestor is complex. Rufus loves and controls as master. Alice loathes Rufus and does not allow herself to feel otherwise through out her life.

Finally, Butler examines the relationship between Rufus and his other slaves. This too is demonstrated to be complex and intricate. As Dana observes “… slavery of any kind fostered strange relationships”. (p. 255–256)

Also read: Book Review: The Dictionary Of Lost Words – A Feminist Take On Language And History

Kindred

Is the relationship that slavery fosters between a white slave owner and his slaves one that can be characterized as kindred? Who is kindred to whom? Is Dana kindred to Rufus, the white slave-owning ancestor? Is Kevin kindred to Dana, a white man in 1976 who possibly shares many values with her? Is Dana kindred to Sarah, Alice, and other women black women slaves of the antebellum south who share the experiences of slavery with her. Do we choose our kindred as much as we have our kindred imposed upon us? As one of the slave men tells Dana

‘She means it doesn’t come off, Dana,’ he said quietly. ‘The black. She means the devil with people who say you’re anything but what you are.’ (p. 249)

An Indian Story

Can time travel, a la Kindred, be used to bring alive historical social injustices in the Indian context? I would think that this is an exercise that is simply waiting for a fiction writer to take up. Since there are many who “don’t see caste”; who believe that they live in a “gender equal” world; this might be an ingenious way of demonstrating how these claims are moot.

Can time travel, a la Kindred, be used to bring alive historical social injustices in the Indian context? I would think that this is an exercise that is simply waiting for a fiction writer to take up. Since there are many who “don’t see caste”; who believe that they live in a “gender equal” world; this might be an ingenious way of demonstrating how these claims are moot. There’s more than one book idea here. In a world that increasingly recognizes the intersectional nature of experiences, permutations and combinations of caste, class, religion and gender promise to make important and significantly different revelations about social injustice through time in India. If one were to combine the two important variables of time in the past and regions in India, the resulting stories are likely to be numerous, mindboggling and hitherto unplumbed.

Reference

Butler, Octavia E. Kindred: The ground-breaking masterpiece. Headline. Kindle Edition.

Sumanya is a development sector professional in Mumbai. She reads, writes, dances and knits in her spare time.