The first time I picked up a needle and hoop was at the age of 25. A serial hobbyist with anxiety disorder, who was newly single after a bad break-up, I picked up an embroidery kit from the fancy stationery shop at F.C Road. The precision of every mark made, and the poetry of the designs forming on the surface as I kept wounding the cloth, struck me strangely familiar.

While growing up, the embroidery was something I associated with the angel of the house archetype. There were one too many Victorian women on my bookshelf who sat around conspiring to capture some self-important man’s attention with a thimble and needle cushion on their lap. I saw my mother tending to all the mending and sewing work that the house and its incompetent members needed.

I distanced myself from threads, even though I would thumb through her embroidery books and gush at the beautiful patterns. Today, I sit with my embroidery box and hoops whenever I feel my thoughts scatter or spiral. The assurance of a needle weaving in and out of consecutive weave holes to create a single neat stitch calms me down. I wonder now if my mother calmed her frayed nerves in those afternoons that she sat embroidering edges of old table cloths for reusing.

I often sit with the ghosts of my women who were boxed in tasks and duties of the household and chat with them about their art as I fix my embroidered menstrual cup on a piece of felt with a blanket stitch. But this piece is not about those metaphysical conversations, instead, I decided to reach out to a few young embroidery artists I have had the opportunity to know, be inspired, and learn from. (The following questions and answers were conducted as one-on-one interviews that I later weaved together. I have majorly quoted them verbatim, with slight changes to help the conversation flow more naturally.)

In conversation with Bangalore-based textile artist Anuradha Bhaumick, popularly known as hooplabackgirl on the gram. Her work has been featured on platforms like Modern Met, Vogue, etc. Researcher, artist, and owner at Echoes – Gunjan. They are an alumnus of Kala Bhavan and presently a Ph.D. scholar at Jawaharlal Nehru University. Independent visual artist from Punjab, Mandeep Kaur. She is an alumnus of Kala Bhavan, Textile Department. For the last few years, she has been working with Chhoti si Asha while also building her own practice. Mumbai-based artist Koshy Brahmatmaj. She creates works about daily life in the forms of books, paper art, fiber art, embroidery, sculpture, drawings, study, research, and documentation.

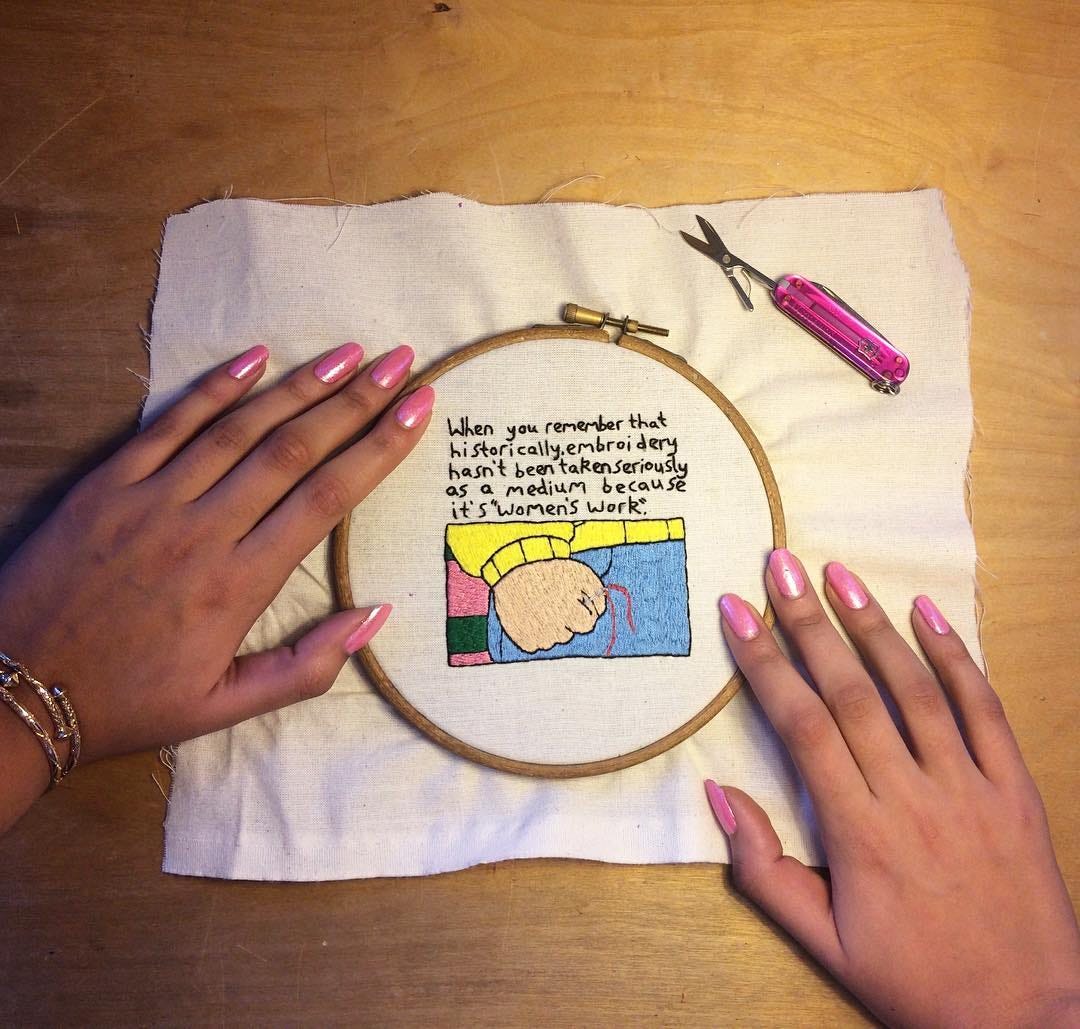

Do you think embroidery has been a gendered art practice? How do you associate one with the other?

Gunjan: I always thought it was a very gendered practice, including crochet and knitting. I grew up with significant dysphoria and I tried my best not to be associated with being a girl. My grandmother tried her best to teach me this art form, but I refused because I saw it as a “girly” practice. I was really bad at sports, but I would rather do that than sit down and stitch.

Anuradha: I grew up learning the language Hindi wherein you divide the words into stree-ling (feminine) and pu-ling (masculine). Classification tools such as roop ki aadhar or arth ki aadhar – are used to determine if a word is masculine or feminine. Kaarigari, bunai, and haath-ka-kaam are words that measure up to be grammatically feminine, and I grew up with that knowledge. So yes, it has been gendered.

G: Around my teenage years, I realised there was lesser freedom attached to being a “girl”. I thought knitting and embroidering were very indoor practices, used to keep people inside, and I liked my freedom. I measured the femininity or masculinity of anything based on who gets more freedom and why. So I distanced myself from anything that measured up to being “girly” so that people would stop looking at me as a “girl”. It was only later when I started becoming comfortable with who I am, that I started embroidering and crocheting.

Embroidery has played a huge role in knowing myself. I started back when I identified with the markers assigned to me – a straight cis-woman. I struggled with the early stigmas associated with this art form. Yet, this is the practice that taught me patience and gave me space to think (introspect). As a non-binary, ace, bi-romantic person, I feel like if I did not have the time and calm that embroidery provided me, I would have had a harder time. Especially, working from references helps me navigate my headspace, my past, and trauma. I love this form so much that I don’t think I will ever give it up. It helped me understand and accept myself

A: I started embroidering at the age of five and at the age of ten, I was at a boarding school in Delhi. It took me many years to dissociate this art form from its gender stereotypes. I wish unlearning was easier and faster. These hardwired associations are difficult to be done away with, but here is hoping we can change our perspective.

Mandeep: I do think it is changing. It used to be an art practiced by the female members of a household. But today I know many artists, like Pascal Monteil from France or my own junior from Punjab, Gurjeet Singh, who are using embroidery as a medium for their art practice.

Koshy: I feel like it is similar to cooking when it comes to associating gender with practice. In commercial textile setups around the city, I have only come across men running sewing, embroidery, and other textile-based business. Whereas, when I share my work with people, I often get responses like – my mum/grandmother used to do this. It is similar to cooking! The majority of the chefs/cooks continue to be men whereas in individual households it is mainly women who have to cook.

G: I think as we are actively seeing a change in the notion and practice of gender, things are changing. As I started knowing myself better, seeing myself differently, suddenly it was not the same. For me, it is not gendered anymore. Even though it is still considered largely feminine. It is a male’s profession when they sew or embroider, but for a female, it is a hobby. But I think things are changing. One of my best friends, Deepak, would dabble in a lot of things. So when he picked up embroidery it felt natural, that oh men can do that. Even in Kala Bhavan, I saw more men in Textile Department and more women in Sculpture Department, than the opposite.

M: But the change is slow. (Cis-het) Men are not comfortable with a form that is still considered feminine.

A: I am still outgrowing that gender association with this form. Whenever I see a (cis) male practitioner I feel so inspired and surprised; I have so many questions for them. But when I see a woman practicing it, my reaction is, “oh that is nice”, and this should not be the case. This prejudice is unconscious. I am still trying to learn and unlearn.

Also read: A Needle With A Point: Singhleton Is Stitching Stories Of Dissent

Does your practice primarily involve reviving the old traditions or are you formulating fresh methods?

A: My mother has been a big influence in my life. I grew up seeing her upcycle, re-upholster, recycle and create things from scratch – that included embroidering, knitting, mending, and crocheting. She still collects old pieces like tea towels, uniforms, handkerchiefs, rice packets, and fragile bits of clothes – to turn them into blankets or Kantha. So, having grown up with these traditions, my ethos has been rooted in them. I use a lot of collage and applique methods, repurposing old textile. So while the scenes and themes are contemporary, my methods are majorly traditional.

M: The first embroidery I did was also in Kantha. Because I started practicing embroidery while studying in Shantiniketan. I was so inspired by the women I saw there, everyone was casually practicing Kantha embroidery. So I think I keep going back to traditions for inspiration.

A: I think it has been both for me, reviving the old and finding the new. Knowing the history of any practice is very important. So I like to be thorough with the past – what were the struggles, how did they resist them, what were the mistakes made, etc. Without the knowledge of our ancestors, in any field, we can never learn something completely.

G: There was this beautiful saree my bua embroidered with phulkari when she was pregnant. She never wore it and I have it now. So, I saw it and started trying my hand at phulkari but I realised that it was not for me. I knew chain stitch before I learned french knots or other varieties. I knew how to chain stitch was used on Japanese textiles and kimonos. I was aware of the history of each method was coming from but I have difficulty following patterns. So I rely majorly on my instincts. Embroidery has traditionally had a tactile quality, but I tend to make very tight forms.

I never formally learned embroidery. I feel like I inherited it from my mother, aunts, and grandmother. In Punjab, we used to have these traditions that women would embroider or make bedsheets, pillow covers or tapestries that they would then take with them after they are married. So my mother had made many such pieces that I grew up with. Every motif and every pattern was calculated. I think that has been a huge influence on my art. My art has very similar, meticulous patterns

K: I am fairly new to embroidery as a medium of practice. I look at embroidered textiles I have at home, read about embroidery, and use those techniques and ideas to make what I want to make.

M: During my work with the NGO, Chhoti Si Asha, I designed patterns using Phulkari (a Punjabi traditional method) for the participating women, even though in my practice these methods are not always present. I even did a mural with the women at Chhoti Si Asha, incorporating the lines and motifs of Bengal’s Kantha traditions. I mean, you have to look back as well as move forward!

G: My research has acquainted me with the Chamba Rumaals and I wish to explore that. It comes from the Pahari miniature art tradition. They had elaborate scenes from mythology embroidered on the cloth and I want to use those elements and translate them in my style.

How important has been your practice in asserting your gender identity, expression and resistance?

A: Embroidery has been historically a great medium of resistance. There is so much to learn from the women of Palestine and Afghanistan who have been embroidering their garments and clothes – writing their stories of resistance on them. Popular discourse considers embroidery as an art of leisure. This form is not just a decorative practice but has had functional purposes – from wars to asserting dissent to recording history – it has been used as a form of communication and record since before Christ.

K: I took up embroidery as a sort of a primary practice during the pandemic. When I think about it, staying home and getting diagnosed with chronic illness was a major influence in starting this practice. Embroidery has been important to me because of its slowness. Even though it is a time-consuming task; its materials are not time-bound. I can keep my thread and fabric aside whenever I want a break.

M: My mother was not a “working woman”, but she did so many things. She multitasked so much, yet found time for her art. I think I draw inspiration from that strength immensely. I am still finding my way, resisting and unlearning the traditional sexism and misogyny of Indian households. I am a person who is feminine and wants to hold onto that identity while also being an artist who paints, illustrates, works in murals, embroiders, and does so many other things. For the child I teach right now, I often take a few of her vocational classes in embroidery. Her mother gets irked, complaining about what use this art form will have. But I am quite stubborn, I think every child should be equipped with all tools. She can choose what she wants to do with them.

G: Embroidery has played a huge role in knowing myself. I started back when I identified with the markers assigned to me – a straight cis-woman. I struggled with the early stigmas associated with this art form. Yet, this is the practice that taught me patience and gave me space to think (introspect). As a non-binary, ace, bi-romantic person, I feel like if I did not have the time and calm that embroidery provided me, I would have had a harder time. Especially, working from references helps me navigate my headspace, my past, and trauma. I love this form so much that I don’t think I will ever give it up. It helped me understand and accept myself.

There is a story I came across about the famous tapestries designed by Raphael. The Renaissance paintings that were converted into these elaborate tapestries were manually made by a group of unnamed unknown women. I get it, it was the artist’s design so he gets the credit. But the labour and artistry of the artefact belong to those women. I do not remember the source, thus, cannot validate this information but the story stayed with me. Even though work has been majorly in recreating or copying the works of the masters, I think it has been a feminist journey. Being a queer individual copying the works of great “men” during a time that is progressively feminist, feels like a reclamation of space. Those pieces are now known as Gunjan’s work!

Were you taught this art form by a family or friend circle?

A: I was taught embroidery at age 5 by my mother. I was a hyperactive kid who would be out of the house by 5 pm to play with my friends and was dragged home around 8-8:30 regularly. So when I was down with chicken pox, my mother did not know how to quarantine me. She got me an old handkerchief and taught me two stitches – lazy-daisy running stitch and chain stitch. In a week or so I was fit to go out, but I didn’t want to. I just wanted to keep embroidering! She had to ween me off embroidery but it always remained at the back of my mind.

M: I never formally learned embroidery. I feel like I inherited it from my mother, aunts, and grandmother. In Punjab, we used to have these traditions that women would embroider or make bedsheets, pillow covers or tapestries that they would then take with them after they are married. So my mother had made many such pieces that I grew up with. Every motif and every pattern was calculated. I think that has been a huge influence on my art. My art has very similar, meticulous patterns.

K: I did go to a design school and an art school, but embroidery is something I have picked up on my own. I have used books, skill share, and YouTube to learn embroidery, but the most helpful learning source has been Tiktok (before the ban) and IG reels. My sibling, who also does embroidery as part of her art practice introduced cross stitch to me.

G: My grandmother taught me my first stitches way back. My bua gifted me my first set of silk threads and phulkari threads. But the person who taught me was my roommate Mandeep. She always looked very calm when she worked on her pieces and I wanted to be in that space. I started with a paper, and the next thing I picked up was this huge piece recreating Van Gogh’s sky with a hand holding a sunflower. I did finish it, and one of the things Mandeep taught me was to keep the back neat. And today all my works have extremely light backs and I owe it to her.

Have you taught this form to anyone?

M: I have. I currently have a student I am teaching embroidery. Gunjan used to be my roommate, and I helped her in her initial journey with threads. Last year I started working with an NGO, Chhoti Si Asha, where my job is to work with 100 women and teach them embroidery among other crafts.

G: I did teach it to my boyfriend and he enjoyed making this small sunflower for his mother. I have taught it to my sister. I even took a small class at Art Rickshaw in Kolkata. A senior scholar, Ajay da, from the Ceramic department attended the workshop and loved it so much that he took it up as a practice. I think he was the best student I had.

Do you consider your practice feminist?

A: I want cis-women, non-binary and trans men and women to be able to see themselves in my work. Which is one reason I don’t make facial features in my work. I want you to superimpose your face in the blanks of my pieces. People often associate women living in peace and living their best lives with a movement of resistance, which in reality it is, unfortunately. But it’s about damn time, it’s normalised. Capturing women, non-binary folks, and trans people in their element, in their safe spaces and absolute comfort, and viewed as human beings are what I try to do when I create a piece.

K: Yes, I do consider this feminist practice. Profanity Embroidery has been a way to express my thoughts and feelings. (Antithetical to the traditional associations made with this art form.)

G: There is a story I came across about the famous tapestries designed by Raphael. The Renaissance paintings that were converted into these elaborate tapestries were manually made by a group of unnamed unknown women. I get it, it was the artist’s design so he gets the credit. But the labour and artistry of the artefact belong to those women. I do not remember the source, thus, cannot validate this information but the story stayed with me. Even though work has been majorly in recreating or copying the works of the masters, I think it has been a feminist journey. Being a queer individual copying the works of great “men” during a time that is progressively feminist, feels like a reclamation of space. Those pieces are now known as Gunjan’s work!

A: Human existence is beyond gender and its walls. The further we go from these hardwired notions, the more we go towards love and rise in love. I want my artwork to be a safe space for everyone, as it has become for me, very much indeed.

Our ancestors often practised this art form without formal recognition. Have you ever faced misogyny related to your practice, its viability in the art world etc.?

A: This question is right in the feels! (chuckles) This is something I feel and experience a lot, but I have tried to bury it in my heart. Embroiderers are not paid as much respect as sculptors, painters, muralists, or new media artists. We do not even get a quarter of the respect they receive. I have been turned away by galleries. Even after being profiled by the likes of Vogue and Vice, things that make me sound pompous, I continue to find no gallery ready to represent my work.

M: I think the first time I faced discrimination based on my practice was in my college. I told my professor that I wanted to pursue embroidery as a medium and he completely snubbed me. I remember one of the first pieces that I had worked on for months was a mandala using traditional motifs and methods. The day I displayed it he said it was nice, but it was not art! Such a comment from a teacher was extremely discouraging. But everyone thinks similarly, including the academic world.

The misogyny is complicated by the intersection of class. The artisans of the oppressed class are never considered in the same light – in fame or money. Embroidery is considered an art form of artisans, majorly women. An embroidered saree requires an immense amount of work. An artisan is paid nominally for it. Even bigger designers who can afford a higher price margin do not end up paying their artists as much as they deserve. I want to work with these artists, especially women, and grow a team. But I am struggling to understand how I will be able to pay them what they deserve. People already argue with me about my prices, reasoning that they can buy an oil painting at that price

G: When I started embroidering I was in Shantiniketan, surrounded by really diverse practitioners. So, I did not face any misogynistic stigma about my practice. What I faced instead, was a more latent variant of the stereotype when I quoted my price. When I see Gurjeet’s work today with beautiful embroidery and soft sculpture (working with queer themes), represented in galleries and selling so well – I realise it is seen as a man’s work. He deserves every bit of attention and success. I wonder what happens if it is a female-bodied person? Will an indigenous traditional “artisan’s” work be considered valuable enough to be displayed?

A: I am extremely grateful for the love and the work I am doing, but at the same time, I know the reality of writing to a gallery or applying for an exhibition – I am “just” an embroiderer with no fancy art degree. I hope someone reads this and something comes up! Even Jerry Saltz, the art editor of the New York Times, said in a podcast that he doesn’t take embroidery seriously. I remember getting angry, but it is also immensely demotivating. But then you see Ipnot from Japan and Danielle Clough from South Africa – how their bodies of work have been internationally recognised and appreciated. It is hopeful. I hope all my contemporaries, the artists yet to arrive, receive a fraction of the respect we deserve. And of course some of the money we deserve! Oh, the questions we face when we quote a price. The sneer and horror! We gotta take it with a pinch of salt but also hold our ground.

K: I think this will illustrate my answer. A regular conversation when someone asks me about my practice goes something like this: What do you do? I do embroidery. Embroidery on clothes? On fabric, yes. Ohh! My mother used to do this in school / oh my grandmother did this / women in our community do this. Oh, nice! Sahi hai! People buy this!? You make money off this!? I should also tell my mother/grandmother/women in our community to sell.

M: I still feel unsure of my practice. People, even close ones, keep commenting on it. My partner often says how nice my embroideries are but I have so much potential! So it is a struggle to keep motivating myself. I know I can do many things, and use many other media, but this is what I love. Especially since my work has used a lot of floral motifs (commonly associated with decorative embroidery) I question its value as “art”, and people keep asking, where is the art? But I have to stay true to my art and keep practising no matter what people say.

G: The misogyny is complicated by the intersection of class. The artisans of the oppressed class are never considered in the same light – in fame or money. Embroidery is considered an art form of artisans, majorly women. An embroidered saree requires an immense amount of work. An artisan is paid nominally for it. Even bigger designers who can afford a higher price margin do not end up paying their artists as much as they deserve. I want to work with these artists, especially women, and grow a team. But I am struggling to understand how I will be able to pay them what they deserve. People already argue with me about my prices, reasoning that they can buy an oil painting at that price.

M: I think one of the most important things missing is education. People do not understand or appreciate the labour that is expended behind a single piece. We need to build a culture and awareness about this practice so that people can recognise and respect both the art and its artists.

Also read: Meet Sarah Naqvi: The Textile Artist Who Sews Feminist Embroidery