April is Dalit History Month, a much needed education for many of us whose schooling was limited to upper-caste struggles. As a part of the information being shared, we at Feminism in India recently shared a piece about how Ambedkar’s standpoint was inherently feminist. However, there is a need to discuss why feminism as a whole both draws from and contributes to the anti-caste, or anti-Brahminism movement. In this piece, I attempt to superficially overview how these struggles do not, and cannot, be made sense of in isolation.

Reproducing Caste

The Brahminical caste system is an oppressive occupation-based hierarchy that limits lower-castes and Dalit Bahujans from access to a range of decisions such as drinking water from a well to getting a promotion at a job. In its current form, Brahminism is also a system which emphasises the need for maintaining the ‘honour’ and ‘virtue’ of the upper-castes. Because of the fact that women’s reproductive capabilities are necessary for the reproduction of caste-lines, Brahminism has severe implications on the sorts of decisions that women are allowed to make.

The idea of ‘protecting’ the caste by restricting its women is not isolated to the ‘backward’ khap panchayats in Harayana, but is a part of an every day reality that most of us do not realise or acknowledge. Every day, matrimonial ads attempt to find ‘desirable’ partners within caste-groups, such that the couple can ultimately reproduce their caste by having children.

One of the understandings of Ambedkar’s path to the annihilation of caste is thus the inter-caste marriage, which weakens the religious justification of the caste-system. But the moral panic around the inter-mingling of castes has deeply contributed to the idea of what makes a ‘good’ woman.

Image Credit: National Campaign on Dalit Human Rights

Defining a ‘Good’ Woman

A ‘good’ woman is supposed to be modest and dutiful, she is not supposed to be vulgar, coarse, or worst of all, sexually active outside of a socially approved (therefore, within-caste) marriage. This results in severe restrictions on the clothes she wears, where she goes, and who she interacts with, based on notions of ‘propriety.’ This propriety is arguably rooted in Brahminical fears of the mixing of caste-lines. This propriety is rooted in the fear that women will be sexually involved with ‘undesirable’ men and ‘pollute’ their caste.

Notions of Purity/Pollution

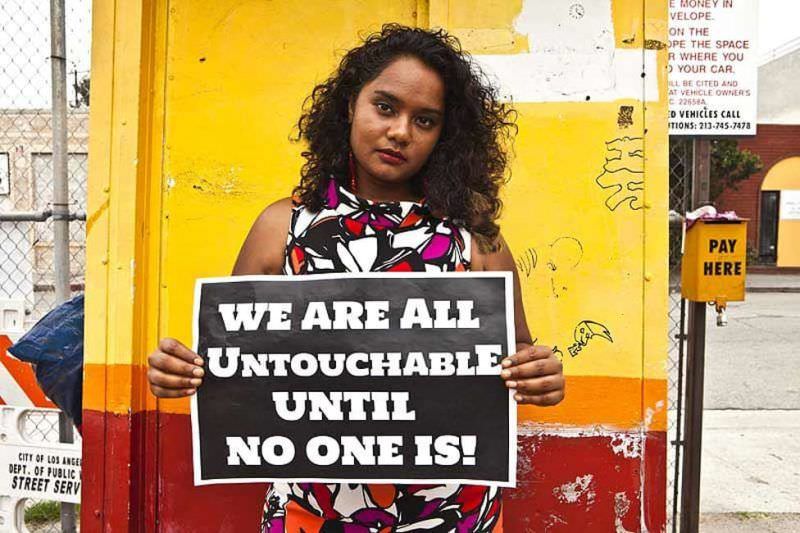

This idea of purity/pollution is inherent to the Brahminical caste system, in preventing ‘pure’ upper-caste bodies from taking up ‘unclean’ occupations or interacting with the Dalit Bahujans who are then forced to. This same purity/pollution is inherent to the understanding of women’s lived experiences, even among upper-caste women.

Menstruating upper-caste women are considered ‘unclean’ and are often not allowed to enter kitchens, pooja rooms, and temples. They are often considered ‘untouchable’ and are forced to live in isolation for the duration of their periods. The taboo surrounding pre-marital sex similarly draws from the stigma attached to a ‘polluted’ body.

These ideas have severely affected the legal and judicial processes in our country. In the history of the Indian women’s movement, incidents like the Mathura rape case are turning points. In this case, the judgement was passed based on the prior sexual history of the rape survivor. The courts saw rape as a violation of the ‘virtue’ of the woman as opposed to the violation of her body and selfhood.

In the case of the reported rape of Bhanwari Devi, this ‘virtue’ became very evidently one that was rooted in Brahminical Hindu notions of propriety. In this judgement, they reasoned that since the alleged rapists were upper-castes (including a Brahmin), they were to be acquitted – as “an upper-caste man could not have defiled himself by raping a lower-caste woman.” These judgements were so deeply entrenched in ideas of purity/pollution, that is was assumed that men could not and would not violate an ‘impure’ body.

Image Credit: @dalitdiva

Mainstream Feminism

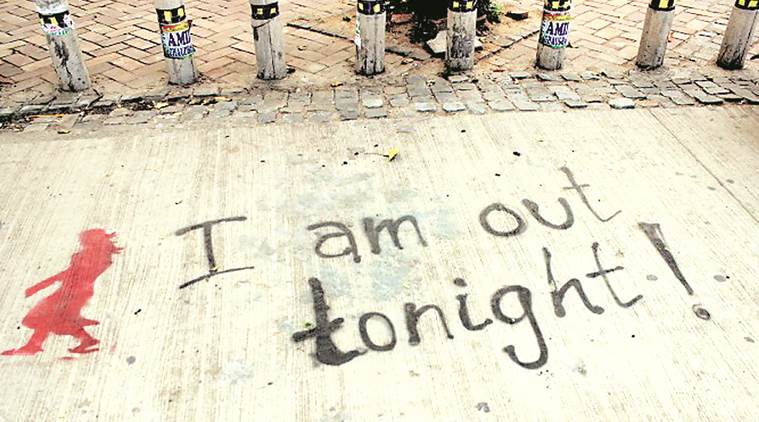

This is not simply history but very relevant in post-2012 India, where the mainstream feminist rhetoric has been limited to arguments for middle-class, upper-caste women’s ‘safety.’ This insistence, while well-intentioned, often reinforces the boundaries drawn to prevent inter-caste and class mingling by isolating women. It often also reinforces the singular notion of a ‘good’ woman as one who conforms to Brahminical virtues.

As a response, recent movements such as Pinjra Tod have acknowledged casteism as inherent to the cause of the feminist struggle, and as inherent to several of the diktats of ‘women’s safety.’

Image Credit: The Indian Express

Feminism and Intersectionality

Meanwhile, the feminist struggle is one that aims to understand the importance of ‘intersectionality’ – or that each individual has different privileges and challenges based on the different aspects of their identity. These aspects include gender, caste, class, religion, region, skin colour, and so on. In this context, the struggle of an upper-caste urban middle-class woman is not necessarily the same as that of a similarly located (and thus seemingly privileged) lower-caste woman. Dalit women face the triple burden of caste, class, and gender.

Sexual abuse and violence are often faced by Dalit women who are ‘punished’ for violating their gendered, casteist roles, and less than 1% of the alleged perpetrators of these crimes are ever convicted. The media coverage and response to these crimes is sporadic and hardly extensive.

These internal differences of intersectionality need to be explicitly acknowledged in the feminist struggle for minority rights, even in the seemingly uncomplicated decisions of the employment of domestic labour at home (generally, lower-caste), or the matrimonial ads we see in the newspapers. Brahminical casteism permeates so deep that when LGBT activist Harish Iyer’s mother placed a seemingly progressive matrimonial ad seeking a groom for her son, she still mentioned that an Iyer was ‘preferred.’

Feminism = Anti-Brahminical Patriarchy

Anti-caste activists such as Ambedkar, Periyar, Jyotirao Phule, and Savitribai Phule attempted to educate and mobilise around the idea that Brahminism was oppressive, not just to Dalit Bahujans, but to women. At the same time, the Dalit movement has encountered severe internal critique for being internally oppressive to women in the past.

Scholars such as Uma Chakravarti and V. Geetha have written extensively about the historicity of the intersections of gender and caste hierarchies, even pointing out that the most careful supervision and surveillance of women and their behaviour is given to upper-caste women to protect their caste-lines. At the same time, the feminist movement has encountered severe internal critique for being internally oppressive to lower-castes and Dalit Bahujans in the past.

But one only needs to think about it to realise that, as a reality, the anti-Brahminism and feminist movements must be intrinsically linked in their fight.

Both fight against the essentialisation of bodies into certain roles that are defined by birth, both fight against the necessity to conform to certain occupations, both fight against restrictions on access to space and decision making – both fight against the Brahminical notions of ‘virtue’ that are defined by ‘purity/pollution.’

Movements cannot exist in isolation, but must make meaning out of each other, and change through each other. There is a need for conversation not just within feminist spaces and anti-caste spaces, but between them. The anti-Brahminical struggle and the feminist struggle are not separate movements, but are separate entry points into a similar struggle against the Brahminical patriarchy. If that sounds complicated, consider it this way: Both believe that everybody should be equal. Feminism and anti-Brahminism go hand in hand because according to the logic of both the struggles, some cannot be ‘more equal’ than others.

Image Credit: Feminism in India

About the author(s)

Bhamini is a Masters student who alternates between working on her dissertation and getting worked up by the state of the world. She writes in an attempt to translate feminist discourses from academia to plainspeak.