Art plays a pivotal role in subverting dominant ideas, especially when it’s the work of a phenomenal woman artist. Among the many significant artists in India, one who has emerged as a definite symbol of cultural insurrection is Amrita Sher-Gil – an artist with astounding sensibility and talent. Her work is a milestone not only for women’s art in India but for contemporary art on a larger scale. With the rare ability of depicting liveliness in the complex realities of her paintings, she portrayed the ideas of human bonds like no other artist of her time.

Cut to contemporary times when the nation is facing the heat from a fascist and vicious government, where ideas of normative heterosexuality and nationalism are dominating and oppressive, it becomes an important feminist inquiry to recall and study Sher-Gil. She dealt with the questions of gender, identity, and sexuality, and did not fail to evoke feminist engagements through her art.

So here is the life story of a woman who once said, “Europe belongs to Picasso, Matisse, Braque and many others. India belongs only to me.” This is the life is Amrita SherGil, the Hungarian-Indian painter who unfortunately and tragically lived a short life of 28 years, but changed the face of art in India.

Early Life and Art

Amrita Sher-Gil was born in Budapest Hungary, on 30th January 1913 to Umrao Singh Sher-Gil Majithia, a Sikh aristocrat and a scholar in Sanskrit and Persian, and Marie Antoniette Gottesmann, a Jewish opera singer from Hungary. She was the elder of the two daughters and her sister’s name was Indira Sundaram.

Known to be a rebellious girl by nature, Amrita was not someone who liked going to school as a child. She was enrolled in the Church of Jesus at St. Mary Convent School in Shimla. She was a non-believer and condemned Catholic rituals, and this eventually became the reason her formal schooling to end, since her teachers found out about her ideology and expelled her in 1924.

She spent most of her time painting, playing the piano and learning. Though she always said she wanted to become a painter, her other skills are admirable too. She loved playing the piano. And yet to be a painter came naturally to her. She wrote, “It seems to me that I never began painting, but that I have always painted. And I have always had, with a strange certitude, the conviction, that I meant, to be a painter and nothing else.”

Later Amrita’s uncle, Ervin Bakatay, who himself was a painter recognized her talent and suggested that she be taught in one of the finest art schools of Paris. She went on to study at Academie de la Grande Chaumiere Institute in 1929. While there, she painted in her own style, not caring to follow the standard norms of her classes. But soon she lost interest in learning there and with the help of one of her professor Lucien Simon, she went to a premium institute called Ecole Nationale des Beaux Art. She found interest in painting the human form and did model painting too. She sketched both in pencil and charcoal, over a hundred male and female nudes. Between the years 1930 – 1932, she produced more than 60 paintings; still-life compositions and landscapes but mostly self-portraits and portraits done in oil. She led an intellectually stimulating life in Paris. While living there, she had big exhibitions showcasing her work in the 1930s.

In 1935 she decided to return to India to pursue her artistic instincts. What affected her most were the Ajanta and Ellora caves which completely transformed her art. She married Victor Egan who was her childhood friend and her first cousin. He had training in medical school and Amrita’s mother was not very happy with her decision. Yet Amrita was not interested in marrying anyone else. They got married on 16 July 1938 in a civil court and she continued painting after marriage too. After the couple moved to India because of the war-like situation in Europe, they decided to live in Shimla. However, with time, Amrita went into depression. During this time, she painted two pictures – ‘Ancient Story-Teller‘ and ‘The Swing‘. The prior is among the best pictures she had painted since her return to India. It won awards at the Indian Academy of Fine Arts, Amritsar.

Along with painting, she also wrote letters to the important people in her life, which are compiled in a book by Vivan Sundaram. Her words showcase her impulsive, exciting, independent, fierce, and intense life.

Amrita’s Work

Her work was phenomenal at many levels. It is indeed true that she painted herself over and over again in different styles of clothing, moods, and expressions – Indian and European both. Being an artist came naturally to her. It is said that when she was 7, she would illustrate stories that she had read. Amrita herself recalls, “I have drawn and painted, I think from the tiniest childhood, and I recollect that the presents most looked forward to as a child were paint boxes, coloured pencils, drawing paper and picture books. Rather independent at that age, it will be of psychological interest to note that I detested the process of ‘colouring in’ the drawings of picture books. I always drew and painted everything myself and resented correction or interference with my work.”

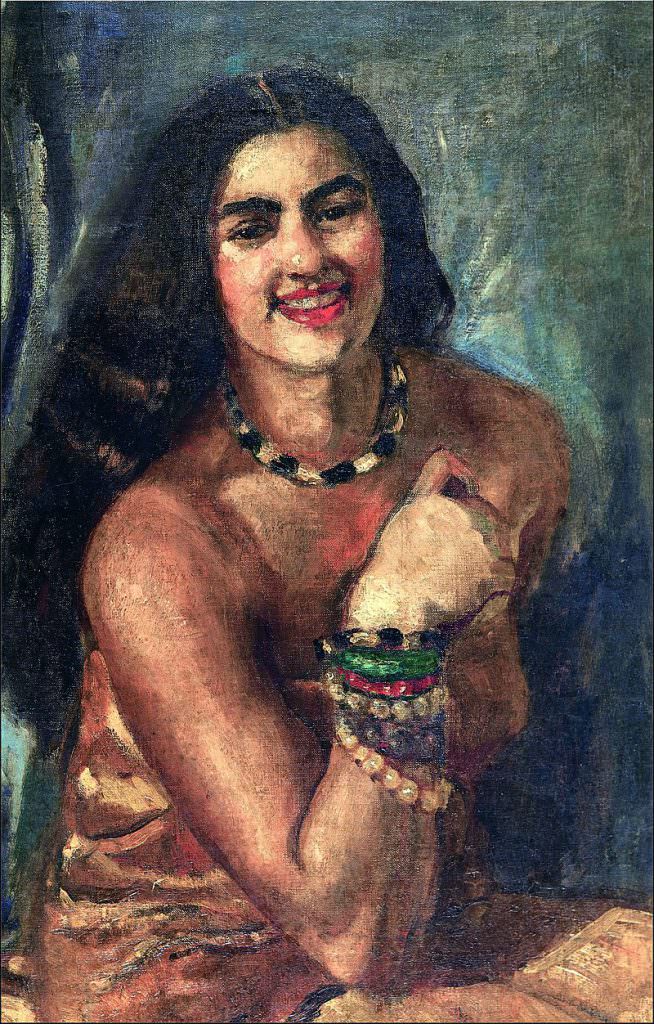

In one of her most dramatic self-portraits, Amrita is dressed as a Tahitian woman who, in a breathtaking close-up, fully occupies the canvas space. Like most of her paintings, this too stands as an epitome of something that is truly and deservingly larger than life.

Sher-Gil, with parents who had different cultural backgrounds, embraced both the worlds. There were times when she would embrace her Indian-ness in Paris, during exhibitions showcasing her work. She would do it by adorning a saree in public events. There is no doubt that she pictured herself as truly unique in the absolutely male dominated world. So the fact that she has been reportedly referred to as India’s Frida Kahlo, is not something that should sound surprising.

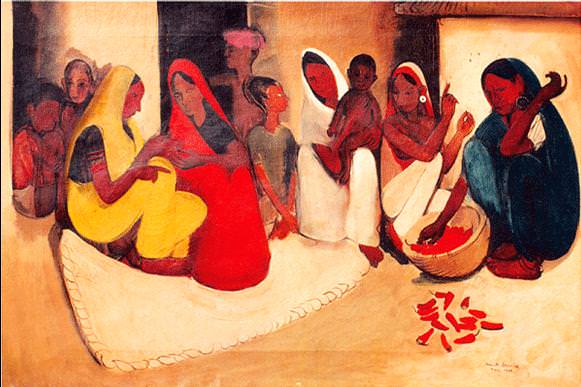

In 1936, the press in India started to finally take notice of Sher-Gil’s work, as something that was beyond the ordinary. She also won two prizes at the 5th Annual Exhibition of the All India Fine Arts Society in New Delhi. The next exhibition of her work was held on 20th November 1936 in Bombay. Some of her best paintings at display were the following – Group of Young Girls, On the Terrace, Child Wife, Hill Women, Portrait of My Father, and Villagers. As mentioned earlier, her visit to the Ajanta and Ellora caves impacted her art to a great extent, after which she set out on her journey to South India. In fact, she began to feel haunted by an intense longing to return to the country in order to find the painter inside her. Even her professors believed that the actual life to her colors can be found only in the expressions of the east.

People like Jawaharlal Nehru were in admiration of Amrita’s work as well. The two of them also exchanged letters, one of which read (to Amrita), “l liked your pictures because they showed so much strength and perception“. Amrita’s South Indian Trilogy is regarded as her greatest achievement. The first in the South Indian Trilogy was Bride’s Toilet’, the second was Brahmchari and the third was South Indian Villager Going to Market. The paintings were called the greatest paintings of the century. She also made Elephants Bathing in a Green Pool and ln the Ladies Enclosure.

Amrita not only had a fiercely bourgeois lifestyle and was very glamorous, but was also very sensual in her own artistic way. She had the rare privilege to be an insider and outsider to the two world apart expressions of her art – the Indian and the Western. She went on to criticize the Indian art of her times and dismissed other schools of art too. Other than Tagore and Raja Ravi Varma, she thought everyone was doing injustice to the idea and concept of art. Beyond that, in most of her works, she identified with the upper-class Indian society. Her liking for painting the distressed poor of India was not unknown, for, in her words, she found them “strangely beautiful in their ugliness“. Majority of the themes in her paintings explored the darker side, the grim side of the subject.

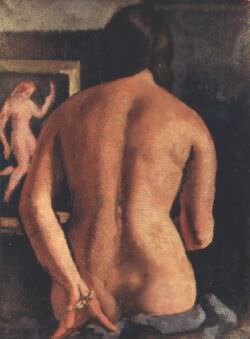

One amazing painting of hers, Portrait of a Young Man in 1930 won a prize at the Ecole in 1931; Marie Lousie, a portrait of her good friend and colleague Marie Lousie Chasseny, 1932 and a painting titled Young Girls, also done in 1932, also won the Gold Medal from the Grand Salon in 1933. In 1931, she painted Torso, a provocative painting in which Amrita used her own nude back as the model of the painting. So to say that the questions of the female body and its expressions and identifications have been started by her way back in the 1930s.

She adopted a free independent provocative lifestyle in Paris. Her sense of liberation was visible through her art and her lifestyle both. It is believed that during the 1930s while she was living in Paris, she lived her life to the fullest and had homosexual relations with her best friend and roommate Marie Lousie Chassney, which both denied. In one of her letters, she wrote to her mother that she would have something with a female when the opportunity arises. She was attached and associated to many men at different points of her life, and is believed to have had a very sexually liberated life for the era she belonged to.

In an article titled Modern Indian Art in the Hindu (November 1936), Amrita wrote, “The Indian art committed the mistake of feeding almost exclusively on the tradition of mythology and romance. I am an individualist evolving a new technique that though not necessarily Indian in the traditional sense of the word, will yet be fundamentally Indian in spirit.” Not to mention her achievement as the youngest ever to get elected as an Associate of the Grand Salon in Paris in 1933.

It was also said that Amrita was known to use her servants as models while painting. And yet she was never part of the world of the Indian peasants that she depicted. Most of her work had the view that was from the outside, from the exterior. Her images seem to have given way for reproduction of binaries of the east and the west somewhere down the line.

Remembering Amrita Sher-Gil

Amrita Sher-Gil died on 5th December 1941 in Lahore. She was 28 years old.

After her death, she transformed into a legendary figure. There have been some biographies on her after her death, though none of them are believed to offer a thorough critical analysis of her work. One needs to find out and inquire into her desires and impulses to paint the pictures the way she did.

She was talented, unique, bold, impressive, and yearned for shades of artistic identities in her work. This paved way for ensuring that contemporary artistic interests remain alive through her paintings for ages to come. An eminent Indian painter, she will remain a prized possession of the modern Indian art. As a woman who belonged to the upper classes in the country, she defied the social norms through her various strokes and different ways of living. The woman did not live to see what a phenomenon she had become over the years, but there is no doubt that she lived a life that was generations ahead of her own, did things that were forbidden for her and was proud of herself.

Fierce and forthright, her art spoke more to the heart than to the mind. It struck a chord no other artist was capable of doing. Amrita not only set an example but also redefined art in many ways. To create art to leave an impact like that, Amrita broke a lot of barriers that reflected her unconventional upbringing as well. She was declared a national treasure artist in 1976, which means that her work in India cannot leave the country. Her’s is an art that moves naturally towards tragedy, reality, and beauty. In one word, her art is poignant.

It is unfortunate that an extraordinary, magnificent woman like her was denied a full life, though her art continues to live on and dazzle everyone. One must return to her work time and again, to understand and find newer meanings to life – the one she depicted through her art. A firecracker woman, her ambitions took her to the world, brought her back to the country she loved, and transformed her art into life. Amrita SherGil was shockingly modern for her time and belonged to, in the literal sense, both the lives she lived, world apart – the east and the west.

About the author(s)

Nupur is a graduate in Women’s Studies. Interests include research, academia, gender, sexuality and politics.