The political world is still very much a man’s world. Even when there is a woman in it, she needs to claw her way through it, making a position for herself, facing more backlash than is necessary. So for Vijay Lakshmi Pandit to hold so many different positions, before and after independence, is an achievement for women through time. Not only was she the first woman to hold a political position in pre-independent India, but she was also the first woman to be the President of the UN General Assembly. She was the face of the newly independent India, representing the country in 3 different countries. She was a staunch believer in the freedom of India and openly condemned colonialism and imperialism.

Early Life and Early Work

Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit was born on 18th August 1900 in Allahabad. She was the daughter of Motilal Nehru and Swaruprani Thussu. Her interest in politics began at an early age and she attended her first political meeting at the age of 16. The political meeting was organised by her cousin, Rameshwari Nehru, to discuss the protest of the treatment of India labourers in South Africa. Her disdain for colonialism can be seen in her work later as well.

In the early 30s, Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit began her official political career. She joined the All Indian Women’s Conference (AIWC), as many women did at the time. Along with Rajkumari Amrit Kaur, Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit pushed the AIWC to reconsider their notion that politics and welfare were mutually exclusive and antithetical. A resolution was passed by the AIWC that under the British government anything done for self-improvement of economic emancipation would be a political problem. Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit went on to lead the AIWC from 1941 – 1943.

The provincial elections took place in 1937 as mandated by the Government of India Act 1935. During this time, Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit was elected as the Local Self-Governments and Health Minister of the United Provinces, making her the first woman to be elected to a cabinet position in pre-independence India. During her time as minister, Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit moved to table the resolution that condemned the 1935 act, instead demanding a new constituent assembly. In 1939, when the British volunteered the Indian troops for the Second World War without consulting the government, Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit, along with the other ministers resigned their posts. With the advent of the civil disobedient movement, Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit was arrested once in 1940, and again in 1942.

Following her husband’s death in 1944, Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit found herself penniless. At the time, a woman could not inherit her husband’s money. Vijay Lakshmi had three daughters, and no sons, and so the money that would be hers was instead given to her husband’s brother. She was distraught at the state that she was so suddenly left in, but pursued her career in politics.

Disdain for Imperialism

After her husband’s death, Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit travelled the United States of America. During her tour she talked about the problems of colonialism and the impact that imperialism had on colonised countries. She pushed for countries to be held accountable for human dignity, equality and rights. She believed strongly in equality and condemned the inherent racism that came with colonialism. During the San Francisco Conference, she called out the Indian representatives as being selected by the British to represent the colonised version of India, rather than the real India:

“I desire to make it clear that the so called Indian representatives attending the Conference have not the slightest representative capacity, no sanction, no mandate from any of the responsible groups in India and are merely nominees of the British Government. Anything they say here or any vote they cast can have no binding effect or force on the Indian people.”

On returning from USA, in 1946, Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit returned to her political career. She was reinstated to her position as minister of Local Self-Government and Health in the United Provinces, and was then elected to the Constituent Assembly later that year. While the men of the Constituent Assembly are well known for their contributions, the women aren’t talked about as much. Out of the 299 members, 15 of them were women. What was unique about these 15 women architects of the constitution was that they ranged from lawyers, to freedom fighters and politicians. It was their experiences as women that ensured some amount of equality in the constitution. Their speeches included topics such as minority rights, reservation, women’s reservation, religious education and schooling.

Vijay Lakshmi Pandit continued to advocate for human rights and equality and condemn the effects of imperialism on colonised countries during her time in the Constituent Assembly. In a speech that she made to the constituent assembly, Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit highlighted the difficulties of shaking off the lasting impression of imperialism, even after countries had already gained independence:

“Imperialism dies hard and even though it knows its days are numbered, it struggles for, survival. We have before us the instance of what is happening in Burma, in Indonesia, in Indochina, and we see, how in those countries, in spite of the desperate efforts that the peoples are putting up to free themselves, the stranglehold of imperialism is so great that they are unable easily to shake it off.”

Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit advocated for the good of the whole, and not to sacrifice the good of the whole for the betterment of the few. “Even though certain minorities have special interests to safeguard,” she said, “They should not forget, that they are parts of the whole, and if the larger interest suffers, there can be no question of real safeguarding of the interest of any minority.“

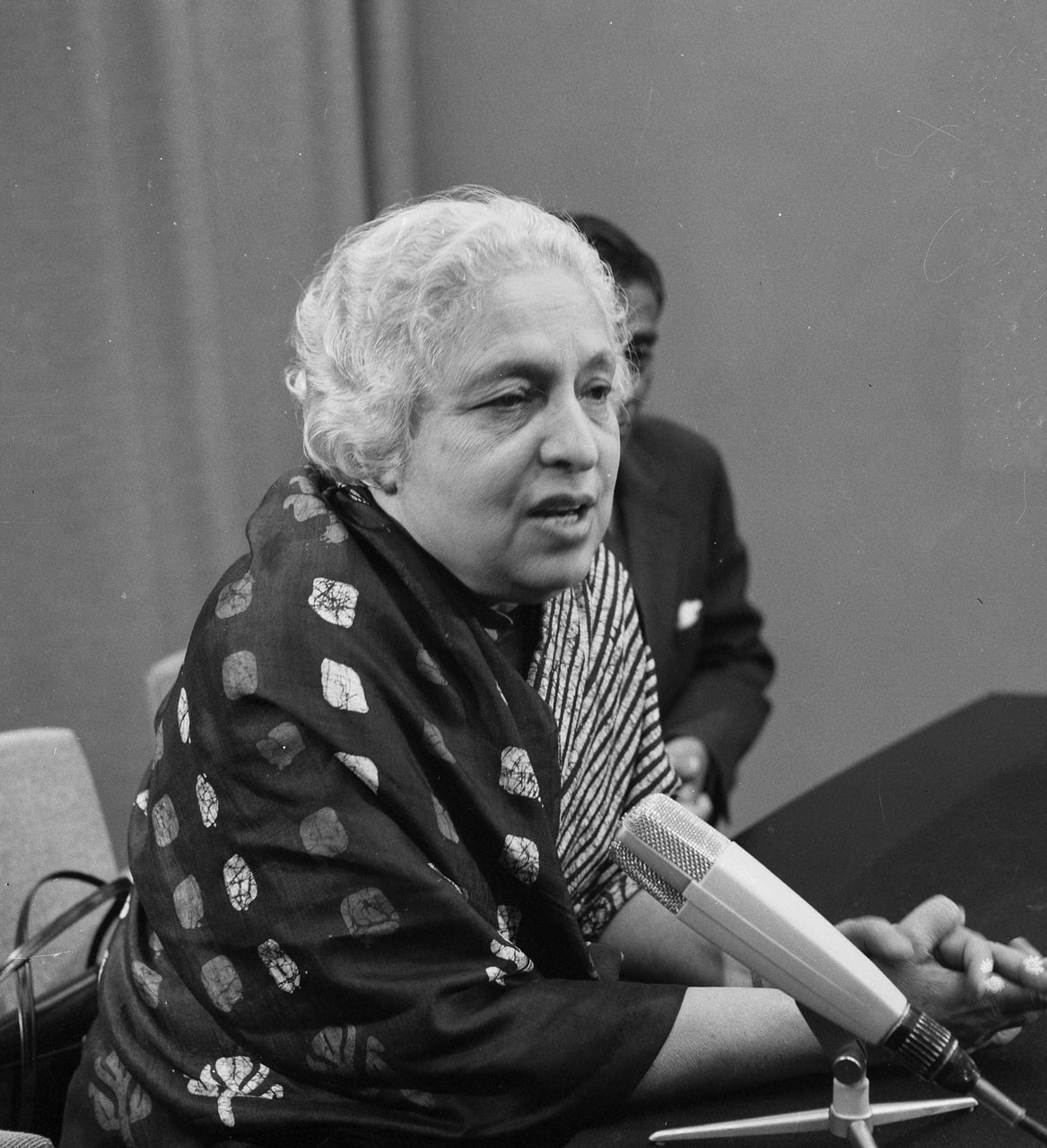

Once India gained independence, Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit was appointed as the Indian Ambassador to the Soviet Union. At the time, she was also the Indian High Commissioner to the United Kingdom, a position that she felt was her best.

Her diplomatic role began with the Soviet Union and the United Kingdom and in 1953, she was appointed the President of the UN General Assembly, making her the first woman to hold the post. Her diplomatic work lasted 15 years and took her to 3 different continents. On returning to India, Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit served as the Governor of Maharasthra from 1962 – 1964. She also served as a minister from the Phalpur constituency from 1964 – 1968. She resigned from the Lok Sabha in 1968 as it was difficult for her to work under Indira Gandhi’s administration. In 1979, Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit served as the Indian representative to the UN Human Rights Commission.

Her Struggles

Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit has fought many battles and broken many barriers for the women on India. Being a woman in politics is difficult even today, but she began her career when it was virtually non-existent. While she acknowledges the privilege she enjoyed by belonging to the Nehru family, she also knows that there were plenty of obstacles that she had to jump through as a woman.

While people constantly tried to remind her that she was a woman, and an outsider, she didn’t let it affect her. When asked if she was conscious of being a woman in a position of power she says “I’ve never been conscious about being different from anybody else because I’ve never been allowed to think that,” of course, not for the lack of trying. She goes onto point out how people in the parliament would bring needles and thread in case she wanted them. “This was not the kind of help I wanted,” she says “I wanted help from their minds.”

This attitude towards women in politics was seen across the world. During her first meeting with Churchill he said to Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit “Because I have accepted you, doesn’t mean that my ideas of women have changed. I don’t want you putting ideas into women’s heads.”

This very quote highlights the kind of struggles that Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit had to face. While she was “accepted” by the prime minister, she and other women of the time were not to assume that women now had an equal opportunity. She was an exception, an exception allowed to exist by the patriarchal world. She wasn’t there because she had seen an opportunity and seized it but rather because she was “allowed” to by the men running the government. As she says in an interview:

“Lots of women now have done much more than I did in my time. The reason why I got publicity was because at that time women had no rights”

About the author(s)

Harini is a freelance illustrator, writer and graphic designer from Bangalore. You'll never find her without a book, some paper and her trusty black pen.