Editor’s Note: This essay is part of the #IndianWomenInHistory campaign for Women’s History Month to remember the untold legacies of women who shaped India, especially India’s various feminist movements. Each day one Indian woman is profiled for the whole of March 2017.

अवघा रंग एक झाला । रंगी रंगला श्रीरंग ॥१॥

मी तूंपण गेलें वायां । पाहतं पंडरीच्या राया ॥२॥

नाही भेदाचें तें काम । पळोनी गेले क्रोध काम ॥३॥

देही असुनी तूं विदेही । सदा समाधिस्थ पाही ॥४॥

पाहते पाहणें गेले दुरी । म्हणे चोख्याची महारी ॥५॥

All the colours have merged to be one. God of colours himself is coloured in this colour.

The distinction between I and You have eliminated upon seeing the God of Pandhari

There is no place for discrimination. Anger and Lust too have disappeared.

Though you are embodied you are formless. I see you in constant state of meditation.

There remains no difference between the spectator and the gaze, says Chokha’s Mahari.

(Translation: My own)

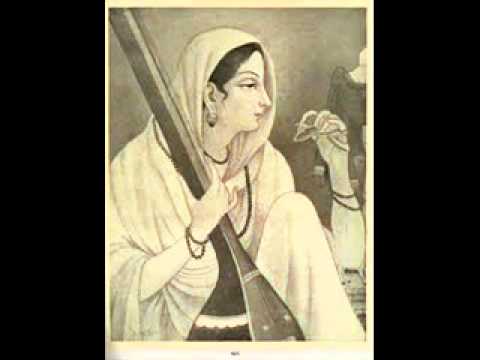

When I first heard Kishori Amonkarji’s rendition of this abhanga (a form of verse employed by saint-poets), I hardly paid any attention to words, but was just taken by her singing. After hearing it for few times, oblivious to the existence of Chokhamela and Soyarabai, I unconsciously assumed that it was written by Saint Tukaram (a widely celebrated seventeenth century saint of Varkari movement). Only later, at a different concert of a young vocalist, did I discover it was written by Sant Soyarabai – the wife of better-known Dalit saint-poet Chokhamela. Since I already knew about Chokhamela by then, I was intrigued about her. More so, because the above-translated abhanga could have been written by any other saint. There seems to have no explicit reference to caste or gender, except for the signature (chokhyachi mahari – Chokha’s Mahari). If one reads it without the signature, one is convinced that the saint-poet has transcended the social identities and material realities into a universal spiritual realm.

Soyarabai lived in the late thirteenth and early fourteenth century near Pandharpur. The saint-poets, of the Varkari tradition, both men and women, belonged to the many different castes of hierarchical caste system. The greatest appeal of the Varkari movement, argues Meera Kosambi, has been its spiritual transcendence of the caste and gender hierarchies of Brahminism from which there was no escape in everyday social life. Naturally, a religious philosophy which provides egalitarian devotional space appealed to the most oppressed sections of the society.

Soyarabai (and other women saints of Maharashtra), unlike Meerabai, do not have passionate love and devotion for Krishna, nor is there a rejection of marriage and defiance towards societal norms. Instead, Soyarabai and her sister-in-law Nirmala (also a Bhakta) write of family, daily existence and their devotion to god Vithoba, pilgrimage to Pandharpur, married life and finding freedom amidst it. There are as many as 62 abhangas of Soyarabai that have survived. However, they have enjoyed very little popular and scholarly attention.

Soyarabai’s Abhangas

Soyarabai’s abhangas convey her poverty, often referring to the leftover food which were distributed among the Dalits after religious feasts. They explicitly indicate the common understanding of the Bhakti tradition as God being both mother and father and chanting the name of the God as the cure for the emotions and problems of the worldly or married life. In addition to these, her abhangas also deal with the sense of inaccessibility of the divine common to all saints. In one of her abhangas, she reproaches God for her status which doesn’t permit her to enter the temple. In another of her abhangas, there is a reference to Brahmins of Pandharpur harassing Chokha:

पंढरीचे ब्राम्हणे चोख्यासी छळीले । तयालागीं केले नवल देवें ॥१॥

सकळ समुदाव चोखियाचे घरी । रिध्दी सिध्दि द्वारी तिष्ठताती ॥२॥

रंग माळा सडे गुढीया तोरणे । आनंद किर्तन वैष्ण्ववांचे ॥३॥

असंख्य ब्राम्हण बैसल्या पंगती । विमानी पाहती सुरवर ॥४॥

तो सुख सोहळा दिवाळी दसरा । वोवाळी सोयरा चोखीयासी ॥५॥

The Brahmins of Pandhari harassed Chokha. God was surprised at this.

Everyone gathered at Chokha’s house. Wealth and Power stood at the door.

Rangoli at the entrance, flags at the gate. Joyous Kirtan of Vaishnavas.

The celebration was like Diwali and Dusshera. Soyara waves the lights of arati before Chokha.

(Translation: Eleanor Zelliot)

Although one does find references to misery of their lives due to they being Dalits, these abhangas are very few. Zelliot muses that it could be due to the fact that since these abhangas are preserved orally, the devotees may have sung only those abhangas which they thought to be appropriate for their pilgrimage to Pandharpur.

Against Brahmanical Patriarchy

It must be noted while the Varkari movement advocated the universal message of spiritual equality, it didn’t give up the caste practices in reality. Shantabai Kamble recalls in her autobiography Majhya Jalmachi Chitterkatha (A Kaleidoscopic Story of My Life) how she was asked about her caste before being served water by a fellow Varkari from a distance.

Until India’s independence Dalits were not allowed to enter the temple and could only pay their respect till the tomb of saint Chokhamela at the footsteps. Vidyut Bhagwat warns against essentializing the voices of saint-poets as only women’s resistance as it obscures their resistance to Brahmanical patriarchy. Since saint-poets like Soyarabai speak about their hardships of daily existence and discrimination, there is also an urge to transform the inegalitarian society. According to her, these voices of Dalit-Bahujan saints must be considered as early feminism in India. She emphasizes that these women saints were part of the early modernity of India and that their struggles and negotiations within their cultural context must be understood and reinterpreted as emancipatory cultural histories. Not only must their abhangas be considered as a source of social commentary of the times they lived in, but a precursor to the modern Dalit poetry.

Soyarabai – A True Mystic

Though Soyarabai’s gender and caste consciousness may not be compared to that of the modern-day feminists or Ambedkarite activists, references in her abhangas to the misery of daily life and restrictions to which they were subjected as belonging to Mahar caste, indicates her awareness of her marginalized status in the society. Through her bhakti of Vitthal, she seemed to transcend material reality and claim her own spiritual space. Eleanor Zellliot thinks of her as a true mystic, “… finding at times the words to describe the indescribable, words that recall the poetry of mystics of many cultures.” She describes Soyarabai as, “A fourteenth century Untouchable woman seems to have risen above the problems of low birth to sing the immersion in the divine.”

References

- Zelliot Enleanor .‘Untouchable Saints: An Indian Phenomenon’, New Delhi, Manohar, 2005

- Kosambi Meera. ‘Intersections: Socio-Cultural Trends in Maharashtra’ , New Delhi, Orient Longman , 2000

- Bhagwat Vidyut. ‘Heritage of Bhakti: Sant Women’s writings in Maharashtra’ in ‘Culture and the Making of Identity in Contemporary India’ edited by Kamala Ganesh and Usha Thakkar, New Delhi, Sage, 2005

Vidula Sonagra is a MPhil (Political Science) graduate from JNU, New Delhi. She has worked as Research Officer at Babasaheb Ambedkar Research and Training Institute (BARTI), Pune. She is a freelance translator as well. She is involved in progressive socio-political activities in Pune, like Karvan.

good very good

I think the 2nd verse is missing a line in the translation.