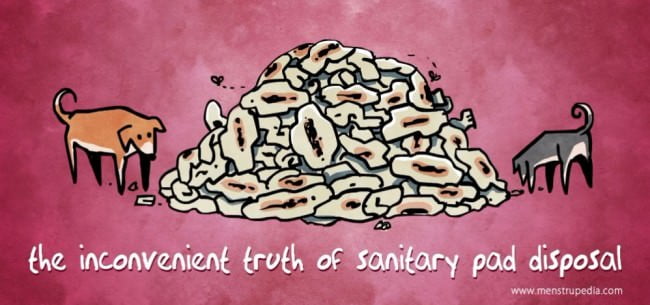

Editor’s note: Approx 125kg of sanitary waste is generated per person during their menstruating years and these sanitary napkins can take 500-800 years to break down! #ThePadEffect is a campaign to advocate for sustainable menstruation and prevent thousands of tons of sanitary waste.

Editor’s note: Approx 125kg of sanitary waste is generated per person during their menstruating years and these sanitary napkins can take 500-800 years to break down! #ThePadEffect is a campaign to advocate for sustainable menstruation and prevent thousands of tons of sanitary waste.Posted by Tulika Bathija

Last May, my teacher friends and I took students of grade 6 (who are currently in grade 7) from our school on a field visit to the Deonar dumping ground in Mumbai. The field trip was planned as part of an interdisciplinary teaching unit on ‘Urban Settlements’ in Humanities and ‘Discrimination’ in English. Through this intersectional unit on settlements, students investigated the planning of Deonar slums and its impact on large majority of Dalit, Muslims and the Dalit Muslim community (Dalits who converted to Islam) residing in the area.

Before visiting the slum area, students had studied the graphic novel, Bhimayana: Experiences of Untouchability written by S Anand and Srividya Natarajan, illustrated by Durga Bai and Subhash Vyam, celebrated Gond artists from Madhya Pradesh. This helped them contextualise the experiences of the marginalised communities and make textual connections. Volunteers at Apnalaya, situated in Shivaji Nagar, had arranged a visit of the demolition area, slum structures and the dumping ground in the vicinity.

It was astounding to find the marginalised communities living in uninhabitable conditions. When we saw the tower of dump, we could not imagine the plight of waste pickers who spend hours toiling in heat and knee deep water to segregate waste with their bare hands. During our visit, we interviewed Ruksana (name changed), a Dalit Muslim waste picker employed on contract basis to segregate garbage. Ruksana, mother of 3 children, now a grandmother has been a waste picker since the age of 15. Soon after her father died, she dropped out of school and assumed the mantle as the oldest child in her family. Ruksana spent her teenage and entire adult life, segregating sharp metallic objects, bio-medical waste, bloody, tattered sanitary napkins and soiled diapers. When she could no longer make ends meet, she worked part-time at night as a caretaker, nursing old, bed-ridden people.

People like Ruksana have led a life of slavery. Unfortunately, we, Indians do not acknowledge the bitter truth that the most deprived and economically disadvantaged people belong to the marginalised Dalit community in India. In order to understand the importance of affirmative action, it is important to listen to their stories, their struggles and their mounting challenges.

While talking to Ruksana I felt a sharp pang of guilt. I would use sanitary napkins and dispose them, in loose newspapers or flimsy plastic sheets. Ultimately, they would roll out and pile up in the dumping ground for Ruksana to separate with her bare hands. She had to take shots and spend the money she did not have to treat cuts, injuries and infections. Was I responsible for this too? Perhaps I was.

I contemplated switching to alternative menstrual hygiene products — menstrual cups or cloth pads. However, the idea of using menstrual cups was a little daunting. I was not ready to make that switch yet. I needed a more viable and comfortable option. I looked up cloth pads online and came across Eco Femme. They make different kinds of pad for the entire menstrual cycle for both heavy and light bleeding days – day pad, first day and night pad. Once I started using them, they felt more comfortable and did not cause rashes or itching. The only drawback was that I had to change pads more often.

Also read: How Cloth Pads Changed My Life | #ThePadEffect

At work, I would carry an extra pad in a cloth pouch, which I also purchased from the Eco Femme online store. Changing pads in the bathroom and carrying the used pad back home, neatly wrapped in a cloth pouch allowed me to break free from the repulsive attitude toward menstruation. I realised how empowering it is take charge of your body, wash your blood with your own hands, soak pads in water, drain them out and hang them out openly in the balcony to dry.

Before this, I would duck and hide from male members at school or in my family. Pads were carried to the dustbin stealthily and disposed shamefully. Using cloth pads has indeed been a revolutionary experience. Alternative menstrual hygiene products not only empower women, but also help create a positive social and environmental impact. We may not be able to change the world, but as educators, we can begin by setting a positive example and be the change that we wish to see in our students.

Tulika Bathija is a whole school ESL specialist, Language & Literature and Theory of Knowledge teacher at École Mondiale World School in Mumbai.

Featured Image Credit: Menstrupedia

About the author(s)

Guest Writers are writers who occasionally write on FII.