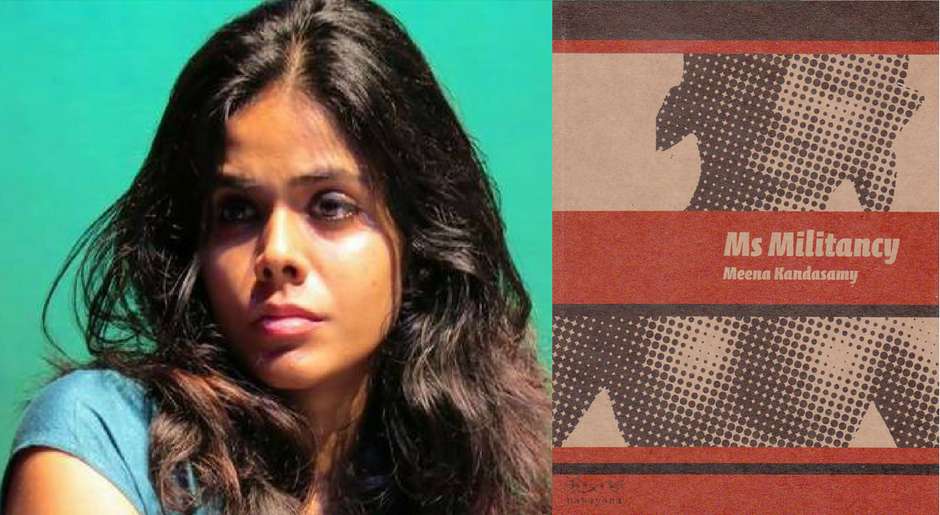

One of the emerging faces of intersectionality in the Indian scene is Meena Kandasamy. She is a poet, writer, translator and activist who fiercely uses her works to speak for the marginalized, and has gained immense appreciation from the literary networks.

Image Credit: http://www.independent.co.uk

Meena is widely known for her unapologetic approach towards fighting patriarchy and the caste system. Being born into a marginalized nomadic tribe, she views caste oppression through a feminist lens, and presents them in the form of anthologies, novels, columns of different magazines, and her social media.

Her first poetry book, Touch, with a forward by Kamala Das, was published in 2006 received widespread acclaim as a unique piece. In an interview with Sampsonia Way Magazine, she says “My poetry is naked, my poetry is in tears, my poetry screams in anger, my poetry writhes in pain. My poetry smells of blood, my poetry salutes sacrifice. My poetry speaks like my people, my poetry speaks for my people.”

I recently read her second poetry collection, Ms Militancy – a title which perfectly suits its unapologetic verses. In this book, her resistance is targeted towards the two main oppressors; the caste-based Brahmanical Hindu society and patriarchy. She tackles multi-layered oppression through confrontational lines, directly accusing the players of this system, stripping them down of their so-called reverence, and exposing their hypocrisy.

Image: http://www.sampsoniaway.org

In the preface ‘Should You Take Offence’, she tells “I do not write into patriarchy. My Maariamma bays for blood. My Kali kills. My Draupadi strips. My Sita climbs on to a stranger’s lap. All my women militate. They brave bombs, they belittle kings. They take on the sun, they take after me.”

Female desire is almost always a matter of scrutiny, and Meena uses it to inaugurate her book. In the very first poem called ‘A Cunning Stunt’, she speaks of the brunt of family and community honour a women’s sexuality has to bear, and that her choices should benefit everyone in the society but herself:

“cunt now becomes seat,

abode, home, lair, nest, stable,

and he opens my legs wider

and shoves more and shoves

harder and I am torn apart

to contain the meanings of

family, race, stock, and caste

and form of existence

and station fixed by birth”

The poem ends with the emergence of the woman’s ‘cunningness’ as she starts pretending in an attempt to not displease the man. “I am frightened. I turn frigid. I turn faker.”

There is a violent seduction in her words, aiming to make the reader uncomfortable, and rattling them towards an ugly reality. She uses themes in contexts often conflicting with the original, which might sound blasphemous to some. She particularly takes on Hindu and Tamil epics, where women are attributed a virtuous and uncorrupted status, which confines their desires and abilities, putting them at the disposition of men to ‘save’ and ‘take care’ of them. Like in ‘Backstreet Girls’, she challenges the chastity forced upon them:

“Tongues untied, we swallow suns.

Sure as sluts, we strip random men.

Sleepless. There’s stardust on our lids.

Naked. There’s self-love on our minds.

And yes, my dears, we are all friends.”

The stanza concludes with the sense of solidarity between women who refuse to fit into the archetype and stand together to fight opposition.

Venturing further into her world of irreverence, she uncovers the cravings of self-righteous men who often mask themselves in piousness in order to maintain their holy position. The human-ness that they hide to portray themselves as higher beings is knocked down in her poem ‘Six Hours Of Chastity‘:

“To increase the number of his sins against recoiling skin,

To drown his sorrow and his loss, to fight the knaves

Who make him what he is, in walks the gambler.

‘After the fifth man, every woman becomes a temple.’

In the darkest hour before dawn, the priest enters there,

Enters her, to make love to her leftovers, fidgeting in his

Guilt and cowardice, like the clinging of holy cymbals.”

A priest visiting a whorehouse is unthinkable but real, and Meena affirms this. The apparent holiness in humans is a sham. No one is spared of their weaknesses, not even the Brahma who is considered one of the sacred trinity of Hinduism as she speaks to that ‘villain’ in ‘Prayers To The Red Slayer’.

She calls Brahma out on his self-proclamation of the creator and a father-figure, despite the existing narrative of him raping his own daughter. “If you’ve ever called to pose for the camera, or give interviews, drop that pen and stop writing our story as if it were your own.” She snatches away his entitlement over people’s lives, of deciding their future.

Moreover, she portrays the women of these myths as self-determined and making decisions on their own terms. For example, Sita from Ramayana is shown refusing to succumb to her husband’s flickering attitude towards her in ‘Princess-In-Exile’:

“Years later, her husband won her back

but by then, she was adept at walkouts,

she had perfected the vanishing act.”

Sita was abandoned when her husband questioned her chastity, but came back to claim her after some time. But she rejects his call, and decides to never go back with the person who doubted her at the first place.

Also Read: A Feminist Reading Of Sita Sings The Blues

Another example of Sita putting herself first is illustrated in ‘Random Access Man’. Here, tired of waiting for her husband to come to her, she chooses a random man to satisfy her. The poem concludes by giving the reader an insight into her perception of masculinity.

“By the time she left

this stranger’s lap

she had learnt

all about love.

First to last.”

Along with desires, the book also advocates Dalit feminism and the atrocities of caste system. Meena lays bare the obstructions and impediments lower-caste women often have to bear as they stand at the intersection of two marginalized identities. In Once My Silence Held You Spellbound, she writes:

“You wouldn’t discuss me because my suffering

was not theoretical enough.”

Here, one can locate the powerlessness of Dalit women as they are unacknowledged not only because of their gender and caste, but also because of their inability to voice themselves in the upper-caste dominated academia.

Perhaps one of the most compelling poems which vigorously exposes the structured subjugation of our society is One-Eyed:

“the pot sees just another noisy child

the glass sees an eager and clumsy hand

the water sees a parched throat slaking thirst

but the teacher sees a girl breaking the rule

the doctor sees a medical emergency

the school sees a potential embarrassment

the press sees a headline and a photofeature

dhanam sees a world torn in half.

her left eye, lid open but light slapped away,

the price for her a taste of that touchable water.”

The brutal discrimination and suppression faced by a little girl means different things to different outfits. While the inanimate well of water only sees a thirsty child, as we move forward towards human establishments, her act starts taking shape of an infringement. This is used for self-interest, as the school attempts to uphold its reputation, and the press sensationalizes it to make money. But for the girl, this episode is only a reminder of a prejudiced world.

Also Read: Six Books By Dalit Women Writers Exploring Lives Lived On The Margins Of Caste And Gender

Meena Kandasamy’s poetry is a powerful testimony to anti-caste feminist literature. She re-constructs the images of women inherited from upper-caste male literature. The dichotomy between the literary and the social context diminishes in her works, and offers an alternative image of women. And most importantly, she empowers through words, bringing out the strength of language.

“Men are afraid of any woman who makes poetry and dangerous

portents. Unable to predict when, for what, and for whom she

will open her mouth, unable to stitch up her lips, they silence her.” (from Nailed)

A pen in woman’s hand can rattle up patriarchy, for this gives her immense power: to educate, agitate and organise. It gives them the power to militate.

Featured Image: The Hindu