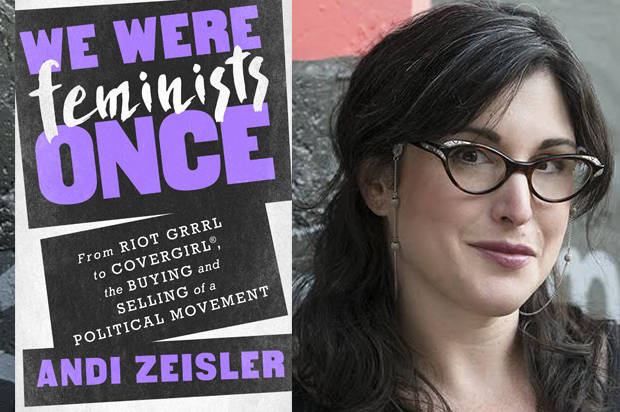

When I first watched Dove’s Evolution film, I cried when I saw how an “average” looking woman was transformed into a “goddess” through the power of make-up and Photoshop. I’ve similarly teared up at the Vicks commercial featuring Gauri Sawant and Ariel’s Share The Load campaign. Everything changed when I was presented with a copy of Andi Zeisler’s We Were Feminists Once: From Riot Grrrl to CoverGirl©.

Andi Zeisler, the founder of Bitch magazine, bases her activism on the premise that pop culture plays an important role in shaping discourse. We Were Feminists Once is a continuation of this work, looking at the seemingly recent rise of feminism in popular discourse.

Zeisler’s book is divided into two parts. Part one – The New Embrace examines the rise of token feminism (or women-centric ideas) in advertising, Hollywood and television, as well as the way the label of “feminist” is uncritically applied to commodities and celebrities alike (is there really a difference between the two in America?). Part two – The Same Old Normal traces this growth to age-old patterns of co-opting social justice by corporations for commercial benefit.

In her history of advertising, Zeisler looks at how advertisers have changed their tactics to market products to (white) women with each change in feminist thought. Early advertisements, such as those for Lucky Slims cigarettes, focused on how women were being “liberated” and “striking a blow against patriarchy” by using their products.

This gave way to the construction of a woman who did exercise a degree of choice but embraced her femininity instead of rejecting it. Recent advertisements seem to have returned to the earlier approach, with the idea of “empowerment” being touted freely. Everything, from perfume to push-up bras to underpants, is “feminist” if advertisers and manufacturers tell you it is.

advertisers have changed their tactics to market products to (white) women with each change in feminist thought.

Zeisler’s assessment of “feminist” television and cinema is equally damning. While she does laud progressive works that emerge from these industries, she notes that the overall situation for women in these industries continues to be terrible. Movies and television shows directed by women and featuring women leads remain a small proportion of overall media. Their success is viewed as tentative, and there is a heavier burden on women who create content to succeed.

In all of these instances, Zeisler traces a few recurring trends: the rise in the use of “empowerment” and the increasing reliance on “choice feminism” being among them. “Empowerment” has become a term that has been loosely bandied about by advertisers and corporations, and has come to mean any act that benefits an individual woman, or appeals to her.

It finds its basis in the idea of choice feminism, or the idea that any choice made by a woman is valid and feminist, irrespective of its impact on her or other women. The rise in choice feminism and empowerment has meant that energy has been diverted from pressing structural issues – such as the falling access to abortion and the gender pay gap – to discussions on whether or not waxing your pubes is feminist. (As she hilariously notes, men do not yet write essays titled “Does My Back, Sack And Crack Wax Betray My Marxism?”)

The effect of choice feminism is to dismiss structural issues – such as the disadvantages faced by women at the workplace – as personal, individual ones. Advice aimed at women increasingly promotes quick fixes (“be more assertive at work”) rather than address the underlying power imbalances.

Also Read: Gal Gadot, Ivanka Trump And The Mainstreaming Of Feminism

In spite of her criticism, however, Zeisler is reluctant to completely dismiss the utility of popular culture to feminism. She believes that when celebrities, television shows and cinema incorporate feminism, it does have the potential to open up new conversations and reach people that serious academic discussion cannot.

While there is a fine line between celebrating feminism and co-opting it, she remains ambivalent about where that line is. She does, however, unequivocally condemn the way capitalism has subverted feminism and ends with saying that the popularity of feminism can never be seen as a measure of its success. Feminism, after all, was never intended to be “fun”.

With her quirky humour and sharp writing, We Were Feminists Once is a swift, fun read. Her use of multiple examples instead of weighty theoretical discussions makes the book extremely accessible to the lay reader. The book, however, seems disjointed in parts, jumping around from theme to theme across chapters.

The chapters on cinema and television seem a little out of place in the rest of the book, which deals largely with the co-option of feminism by corporations. Nevertheless, her book contains useful ideas that allow us to be more critical of how feminism is deployed in pop culture and advertising.

The rise in choice feminism and empowerment has meant that energy has been diverted from pressing structural issues.

Of course, it is useful to contextualize the book before jumping to any conclusions about its applicability to Indian pop culture and advertising. Zeisler was writing in an American context, where the free market has had a longer reign than in post-liberalization India. The realization that women are a separate demographic of consumers came as early as the 1920s, and pop culture and advertising have adapted themselves to each successive wave of feminism to sell them things.

The Indian appeal to (primarily urban, upper caste) women as a demographic by using feminism is, by contrast, more recent. I believe it correlates with the rise of social media and the growing influence of what trends in Europe and North America. The targeted women also form a minuscule proportion of the population – although they happen to be a sizeable market. I do not think the use of the “feminist” marker to market products to women is nearly as prevalent in India as it is in America, though it is certainly growing.

I am also tempted to be less critical because the use of feminism in Indian pop culture still comes with a lot of backlash. You only need to look at the YouTube comments on AIB’s A Woman’s Besties or the response to Lipstick Under My Burkha as an example. Of course, pop culture plays an invaluable role in simplifying complex ideas and disseminating them to a larger audience.

But it is undeniable that the way feminism is used in most of pop culture and advertising is usually unaccommodating of caste, class, religion, or disability. A lot of the persons and institutions creating pop culture benefit from the structural imbalances that feminism seeks to fight.

It is undeniable that a lot of urban feminists have unconsciously imbibed the tenets of choice feminism and use the language of empowerment loosely. Those of us who are invested in the movement must fight back against these tendencies, while certainly using culture wherever possible to keep our message accessible.

Also Read: Reviewing The Riot Grrrl Collection: Feminist Movement From The 90s

Featured Image Credit: Gender Economy

About the author(s)

Vani Sharma is a law student presently based in Bangalore. She has been actively involved in socio-legal issues and research from her very first year of college. When she is not daydreaming about overthrowing the patriarchy, you can find her in Blossoms or roaming around with the latest book she's reading.