In March this year, a textbook in Kerala made ripples through the news for a strange reason. Tucked away in Chapter 4 of the SCERT science textbook for

Image Source: ED Times

An image of the concerned page (which doesn’t mention condom use even once) made the rounds on social media, and became source of much surprise and conversation. But beyond the bizarre, almost amusing falsity of the statement, this error reflects the larger context in which sexuality is discussed in Indian textbooks; a discussion which is fraught with anxious morality, often poorly written and sometimes even inaccurate.

One of the first organised moves to introduce comprehensive sex education in Indian schools was the Adolescent Education Programme (AEP), a joint initiative made by the National Aids Control Organization and MHRD. But what seemed like a move in the right direction, sparked instant fears about Indian culture. The moral panic about teaching students about sexual health and sexuality was so intense that in 2006 the AEP was promptly banned in 13 states across India.

Also read: Is Sexuality Education Against Indian Culture? | #WhyCSE

So when there is no uniform comprehensive sex education across the country, where does this leave students? In the absence of a separate curriculum for sex education, students are left with small chapters in science or physical education textbooks to understand reproductive health and sexuality as part of their formal curriculum. The Kerala incident shows the limitations of this, and how students can be misled if curricula arises out of dominant morality. But how much better are other textbooks?

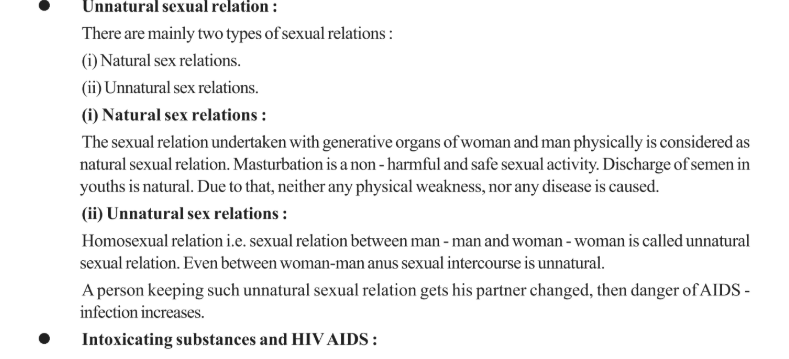

The Gujarat state-board recently introduced a textbook for Yoga, Health & Physical Education. After leafing through the textbook for 10th graders and trudging past elaborate descriptions of Yoga asanas, one will find a chapter on ‘HIV-AIDS awareness’ which contains some concerning bits of information. For one, much like the Kerala textbook, it prescribes not ‘indulge(ing) in sexual behaviour before marriage or other than marriage’ as a HIV-control mechanism. Moreover, it goes on to divide sexual behaviour into categories of ‘natural’ and ‘unnatural’ (pg 47.) As would be expected, the unnatural label is then slapped on any sexual act between people that does not lead to reproduction.

Between Science & Public Health – What Do We Miss Out?

When it comes to reproductive health, science textbooks across states are divided in a similar way- with a section on HIV-AIDs prevention, followed by family planning and a section against sex determination/ early marriage. This almost seamlessly mirrors government schemes that have been introduced over the years for sexual and reproductive health, such as the National Aids Control Programme launched in 1992, or campaigns like Hum Do Humara Do.

While these topics are important ones, sex and reproduction have been limited to public-heath agendas or purely biological descriptions for far too long in Indian textbooks. Is it possible to imagine a dialogue about sexuality in textbooks outside of of science curriculum or a stateist view of health? Human sexuality has always been sociological, affective and embedded in identities in complex and intimate ways. This is precisely why sex education has to deal with more than just anatomy and disease, and definitely has to do better than inaccurate methods of disease prevention, guided by heavy handed morality and fear.

Human sexuality has always been sociological, affective and embedded in identities in complex and intimate ways.

Even when textbooks impart accurate information, one must bear in mind that the act of textbook writing is a selective one; it involves picking and choosing, and consciously leaving out. So what do our textbooks choose to leave out? Across the board, there is an overwhelming silence about two themes that are essential to any feminist dialogue about sexuality: desire and consent, perhaps because these do not come under the obvious ambit of science curricula.

Some textbooks like the NCERT textbook for Physical Education (class IX) and the Tamil Nadu Science textbook (class X) even discuss sexual harassment and abuse, but surprisingly do so without mentioning the concept of consent, let alone affirmative consent. Pleasure is further concealed and sanitized by textbook language. The Gujarat Yoga, Health & Physical Education textbook (class X) mentions that male masturbation is normal because it ‘satisfies sexual emotions,’ (pg 49) but says nothing about female masturbation. Do women and people with other identities have ‘sexual emotions’ at all? Do our textbooks care?

The Case for Feminist Sex Education

While abstinence is a perfectly valid sexual choice, it is unrealistic to prescribe it as the only valid sexual norm for young people, without so much as providing

Though we live in a world full of violence and sexual risk, sexuality can be a positive and enriching aspect of human life; and it is this that our textbooks and larger education system miss out on.

A separate curricula for sexuality that draws from feminism and diverse experiences, would be one that centres basic ideas about pleasure and consent, and encourages students to think about desire, violence, stigma and identity. Moreover, it is necessary to go beyond the gender binary that our science and health textbooks are embedded in and conceive of multiple genders, sexes and diverse bodies. Because whether we teach students about sexuality or not, it will continue to exist- in diverse, complicated and sometimes confusing forms. So isn’t it better if young people have a more reliable, nuanced framework to understand their own changing minds, bodies, interactions and selves?

Also read: Sex Education Needs To Be Queer Inclusive Now!

At the end of the day, it is perhaps unavoidable that textbooks and education will be framed by social morality. When it comes to something like textbook writing, there is no true ‘neutrality’ that we can achieve. What we can hope for then is to draw from a new set of ethics- one that is feminist in its outlook and values sexual autonomy, informed choice and recognizes sexuality as a valuable part of personhood.

At one point, The NCERT physical education textbook describes adolescence as an age of ‘loss of sexual innocence’ (pg 21.) Simply put, this is why a feminist approach to sex education is essential; as it would not see sexuality as a loss of any kind, but instead as a site of human interaction that needs to be imagined differently- without shame, and with more scope for equity, curiosity and expression.

Featured Image Source: Millennium Post

About the author(s)

Anagha is pursuing her MA in Media & Culture from TISS Mumbai.