Art is everywhere and it is political. For centuries, aggressors have been using art to maintain the status quo, while the aggrieved have been using it as a means of protest.

Many critics believe art must simply be looked at, experienced, and that’s it – not studied or judged based on its context. Fair enough for art that doesn’t have a political purpose. It is perfectly rational to look through a kaleidoscope & enjoy symmetry for what it is. But when art wants to speak to us, we have a duty to listen. To simply enjoy menstrual art without understanding the artist’s messages—intended & otherwise—would be to dismiss the story they are telling.

To simply enjoy menstrual art without understanding the artist’s messages – intended & otherwise – would be to dismiss the story they are telling.

So here’s a simple guide to reading menstrual (or any political) art! The nuances are inexhaustible, but this is a good place to start. So let’s get started!

Step 1: Who paid for it?

Art for social causes with corporate sponsorship always has one underlying motive — to sell. It might seem purely political, wholesome even. But can art be true if it is made with the intention to make money off menstruators’ lived experiences?

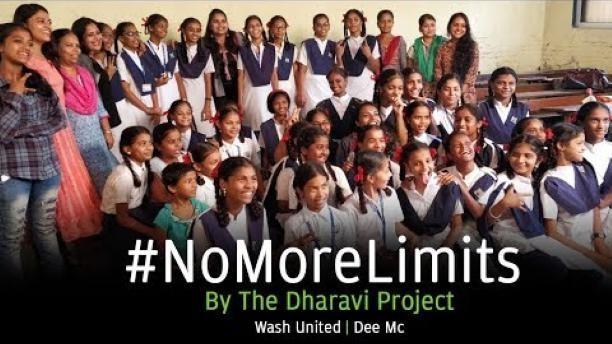

Of course, not all sponsors want profits. For example, we take this rap to raise awareness for Menstrual Hygiene Day (28th May). It features Dee MC, and is sponsored by WASH United in collaboration with The Dharavi Project. WASH is an NGO that promotes health & sanitation in South-Asia & Africa. The Dharavi Project is a platform to promote hip-hop dance, graffiti art, & rap/beat-boxing crews that focus on Mumbai’s least privileged spaces. It can hardly be argued that either of these organisations have an ulterior motive in reminding the world about Menstrual Hygiene Day.

But this cannot be said for all menstrual art…

Whisper Philippines’ collaborated with pop star Nadine Lustre for a video promoting their ‘Curvalicious’ line of pads. “Just like Nadine, be strong, be fearless and be your best self with new soft cottony Whisper!”

Whisper’s campaigns usually have a similar message:

1. Pads are empowering to menstruating women because they allow them to do all activities while bleeding.

2. Even beyond menstruation, pads will give you the confidence to pretty much do anything in life.

This message doesn’t take into account the millions of menstruators who are in fact restricted by their period symptoms, who can’t just “Say yes all day!“. Disorders like PCOD & severe PMS symptoms, to which pads are not the solution, are invisible in this message. Rather than addressing menstruation as a complex & diverse experience, it presents the audience with a standard – as though there is one correct way to menstruate in order to be fulfilled in life.

Thus, Step 1: Ask, ‘Does the producer care first about the cause or their wallet?’

Step 2: Who is the artist?

What social causes can an artist use? What political topics do they have agency over?

Amongst representations of meat and bloodied mirrors in Anish Kapoor’s recent series, lie paintings of bleeding vaginas. He came under fire here for appropriating the female voice to discuss his own abstract understandings of art itself. Rubbishing the concept of appropriation, he has asserted that using the experiences of another demographic is what keeps “the artistic imagination” active.

The question here is not whether men can talk responsibly about “women’s issues”. They can, since no one has a monopoly on feminism. The real question however is, whether men can use “women’s issues” for, (1) their own self-expression and, (2) profit. I don’t believe so and you needn’t agree.

That’s Step 2: Identify the artist & their locus standi. Then ask, ‘Does this matter?’

Step 3: Is the audience important?

As much as political art requires a wide audience, no art can be so universal that everyone accesses the message within it. By virtue of being of a certain medium, a certain language, on a certain platform, an artwork will always exclude many social groups. Thus, a political artist must always consider their audience:

1. The Target Audience, those who need to hear the message being given. Usually, this is those who disagree with the artist’s message, whom the art is meant to transform.

2. The Intended Audience, those whom the artist wishes to send their message to. This could be the same as the Target Audience but often isn’t. For example, while the Target could be a legislator with the power to make lasting change, the Intended could be the public putting pressure on the legislator.

3. The Actual Audience, those whom the art reaches. This should be the same as the intended audience but unfortunately very often isn’t. Due to perhaps lack of strategy / resources or miscalculations, political messages don’t always reach where the artist may have wanted.

This brings us to, Step 3: Is the Intended Audience an important stakeholder? Are the Actual and Intended Audiences the same?

The reason this question is important is because political art doesn’t serve its purpose if it doesn’t reach an important stakeholder in the matter. Test this yardstick! Watch this aptly-named song about periods and ask: Who needs this message? To whom is Peach singing? Who are listening? Are they important or powerful stakeholders?

What is the medium?

What’s unique about this piece is its focus on the economics of menstruation. Often, menstrual art focuses on the stigma alone. Large swathes of red, explicitly yonic motifs, and even real blood – period art often loudly invokes the themes of pain & bleeding or freedom from social bondage.

Bee Hughes points out that issue-specific art often becomes monotonous in its themes & messages. Stigma & taboo are important themes, but audiences may have come to expect pain & social isolation in menstrual art. Hence, Atkinson’s piece stands out – it delivers its take on menstruation in a less loud, less red, less explicitly female image. Not to say this is better; just that it is noticeable because it is different. Through this medium, an exclusively “female” issue is brought into the space of economic issues in general.

In such a manner, upon encountering any political art, it adds an interesting dimension to our understanding if we ask as,

Step 4: What is the scope & what are the restrictions of this medium?

Also read: Why Do We Need The Menstrual Leave Policy In India?

How is menstruation presented?

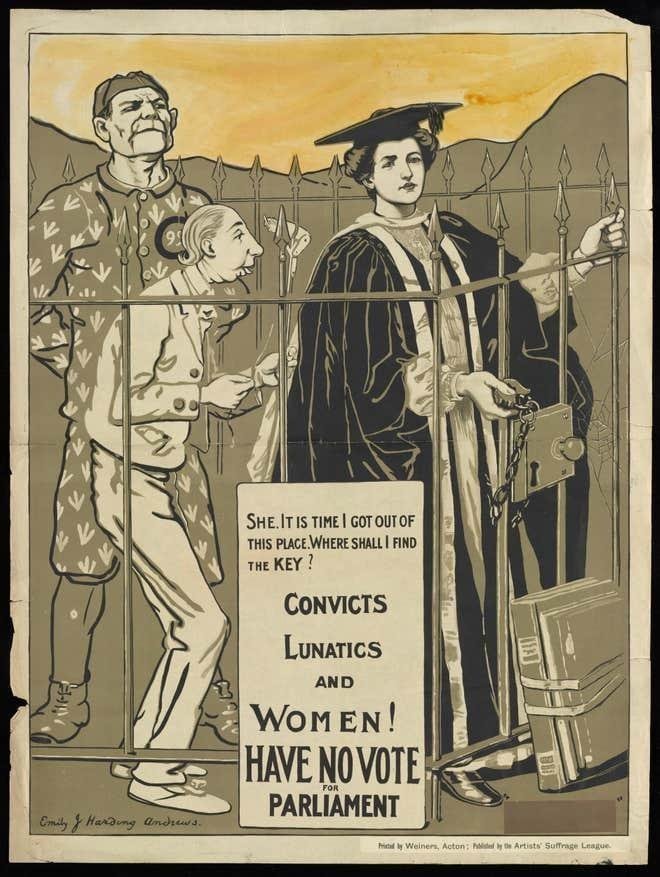

Artists tend to go one of two ways in the attempt to de-stigmatize menstruation:

1. Normalising – Such art says, “Menstruation is routine. My body is functional. There is nothing mysterious about this, hence nothing to fear.”

2. Essentialising – Such art says, “Menstruation is not my curse but what makes me special. My femininity endows me with a spiritual power that is beyond your understanding.”

The invocation of myth and magic keeps menstruators within the realm of all things that cannot be understood. This gives into the male gaze because menstruation is only unfamiliar to those who don’t menstruate. It is wholly understandable to those who experience it.

In the Normalising category we have a video by Allure titled, ‘100 Years of Periods‘. It provides a fairly comprehensive history of period products – their designs, their popularity, & the road to sustainability. It also includes the fight for inclusivity for non-cis-female menstruators, as well as much information on the dominant medical narratives around menstruation and female pain across the last century.

But we are drawn to mystery, such as with Diana Fabianova’s award-winning documentary ‘Moon Inside You‘. To be fair, the film does present many experts who call on psychology & medicine i.e. science to destigmatise menstruation. But it also emphasizes mythical & magical narratives around menstruation – for example, jade eggs from ancient chinese tradition – to a considerable extent.

The invocation of myth and magic keeps menstruators within the realm of all things that cannot be understood. This gives into the male gaze because menstruation is only unfamiliar to those who don’t menstruate. It is wholly understandable to those who experience it.

Normalization takes female bodies out of the space of mystery and into the space of reality. Essentialising female bodies only transforms them from misunderstood and ostracized to misunderstood and revered. Which path to destigmatisation do you prefer?

Step 5: How has this piece presented menstruation? What are the pros and cons of this representation?

And that’s the deal.

You don’t have to agree with this list. The art-world is split on nearly every question. And diversity of interpretation is what gives art its power as a political tool. It makes you think and, often, shows you something you otherwise were blind to. Political art doesn’t just talk, it explains the artist’s life-world.

Of course this list is not exhaustive. But start somewhere. All art is political, and understanding the politics can better help us appreciate the menstrual art.

Also read: Ericka Hart Controversy: “Any Gender Can Get Their Period”

A. Ashni specialised in Political Science from Ashoka University. In the past, she has worked with reputable organisations in the development space like Pratham, Boondh (Campus Catalyst Program 2018-19), and International Innovation Corps. She’s passionate about public social security and inclusive media. Her favorite phrases are ‘Universal Basic Income’ and ‘Progressive Taxation’.She part of the current cohort of India Fellows, through which she now works at Nayi Disha, Hyderabad. You can find her organization on Facebook and Instagram.

Featured Image Source: Art Asia Pacific