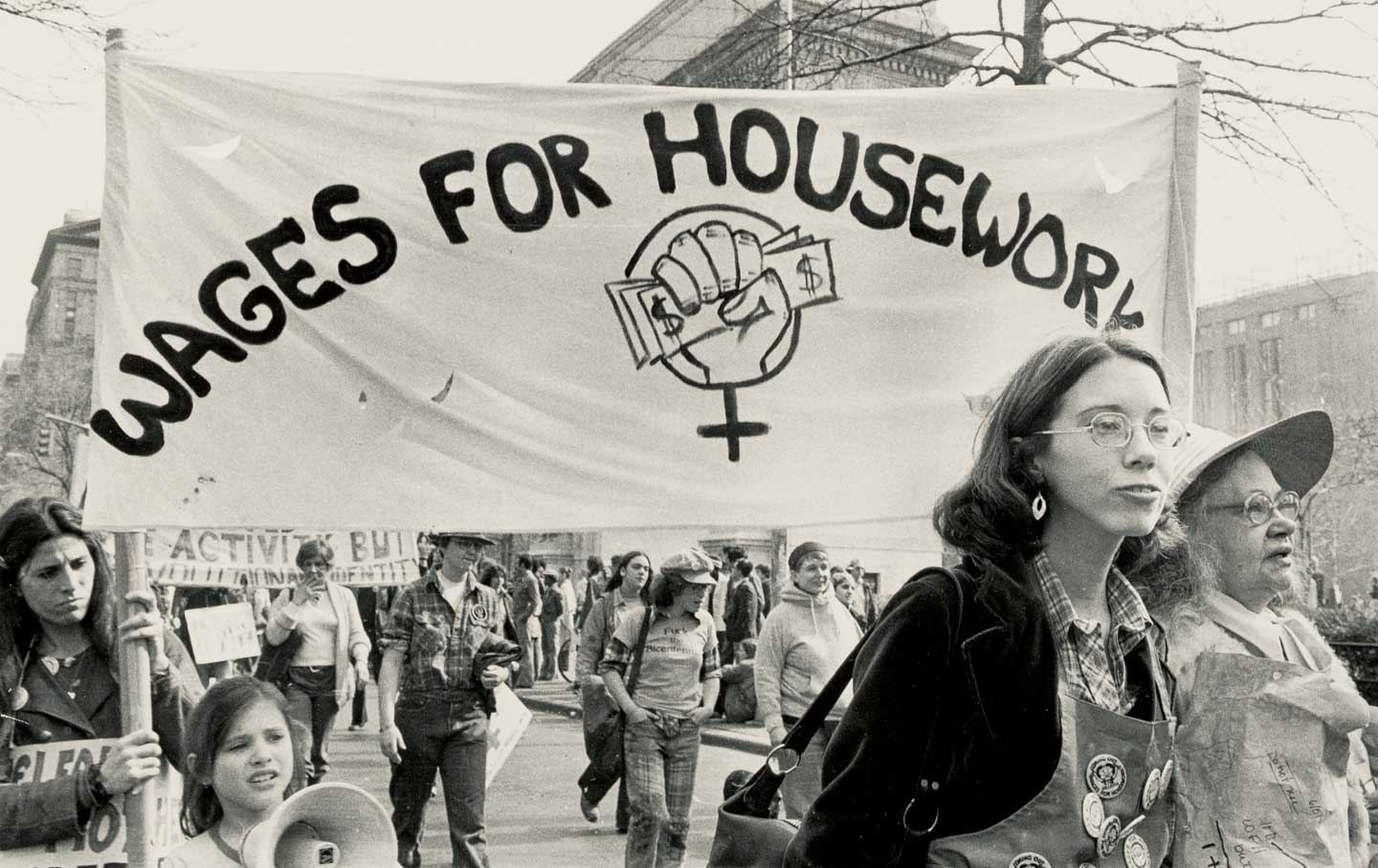

In the view of lengthened lockdown, as more and more of the population stays home, women are expected to tend to the needs of the family round the clock. At the same time the demand for the care income appears to be increasingly spreading across the globe with the recent Global Women’s Strike on April 9th, 2020 in response to the Global Pandemic of Coronavirus. This cannot be seen in isolation from the larger Wages for Housework movement. While work-from-home appears as the new and normalised mode of working to sustain capitalist economy, the traditional care work provided by women which nonetheless is ‘work from home’ and ‘for home’ continues to fit the box of unpaid labour services.

Wages For Housework?: “Pyaar Ki Koi Qeemat Nahin Hoti“

In India, women do the most unpaid care work and domestic work of any country globally, except Kazakhstan which is a country with 94% lower Gross Domestic Product (GDP) than India. Women in India spend up to 352 minutes per day on domestic work, 577% more than men and at least 40% more than the women in China and South Africa as per Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) data.

The unpaid work which not only sustains the economy, but also is equivalent to 3.1 % of the GDP. Given these dynamics that weave the contingencies in the economy of care, it is but obvious to ask, that why after all this, has there never occurred till date any movement like the Wages for Housework movement, which swept parts of the First World in early 1970s and is growing with time.

It is not beyond investigation to infer who constitutes this unpaid labour force – mostly, the women. In India, over a period of time, history has been the witness to many effective and strong feminist movements, wherein women participated, protesting against certain forms of oppression and exploitation at workplace. However, somehow the demand for care income or protest against the invisibilisation of household work never made it to the agenda in an exclusive form. This, despite women rendering household work in most of the domestic spaces in the country.

With the aims of bringing an inversion in the relations of power, overcoming dependency and a fair redistribution of wealth thus conjured up a Wages for Housework Movement across the globe. It was realised that the waged or unwaged women were essentially the same people everywhere, be it India or any other country of the world.

In addition to this varying social position and economic compulsions add yet another dimension to this constituency, where choice seems a remote possibility when it comes to household work. International Labour Organisation (ILO) identifies this as another reason that keeps the women out of the labour force; note the inadequate understanding of the ‘labour force’ itself. While Marxists, pointing to unfair working conditions, are the primary ones to point this out, yet the unionising priorities in India somehow never shifted its attention to this area, for various reasons and an exclusive movement on the ground is yet to make it to our history books.

Though one has to sound caution while looking at the Wages for Housework movement with intrinsic risks like the acceptance of the notion that housework is women’s work. Simultaneously, one can draw on a collective strength by looking at shared solidarities among women for example in Indian urban traditions of mutual self help and cooperatives. This could have been a strong rallying point of organising demand for care income.

With the term ‘housework’ potent of de-gendering housework and unifying solidarities, the conditions prevailing in India, while the second wave of feminism materialised globally, were different and continue to be different in many ways. In order to therefore drive this question home, the answers need to be sieved out from the existing social structures in countries like India. At this juncture one must remember how gender roles operate in tandem with the political lens that rarely sees women as an autonomous electoral constituency. Attitude towards housework thus are shown to be determined by the nature of the particular family relationships as well as by the nature of alternatives to it.

Factors like leisure time, family structure, workers’ organisational capabilities in India and overshadowing of class and gender identity by other identities like religious identity prevents the forming of strong class consciousness. Add to this, the overlap in idea of love with that of care and concern embodied in the way a woman’s role is understood in the Indian society, layered in patriarchy. In addition to a strong idea of the ‘private’ or the domestic realm puts the onus on the woman to cater to the housework and household need.

The unpaid work which not only sustains the economy, but also is equivalent to 3.1 % of the GDP. Given these dynamics that weave the contingencies in the economy of care, it is but obvious to ask, that why after all this, has there never occurred till date any movement like the Wages for Housework movement, which swept parts of the first world in early 1970s and is growing with time.

The socialisation is so deep, that housework and woman are terms that go symbiotically as natural and obvious. Terms like ‘mother’s love’, ‘love is priceless’ misplaced into translating as anything done out of love as priceless. Therefore housework, which is assumed to be a woman’s responsibility typically emanates from that love, hence beyond attempts of quantification, run deep in our general imagination. While the workers or the paid labour force is entitled to some days of leave, a woman in the kitchen cannot risk starving her children by taking a leave.

Also read: House Work? What’s That? Caregiving and (Un)Paid Work

This idea is revered across all social positions in the Indian Society and South Asia at large. While the idea of economic independence and moving out of the house for work is increasingly recognised, demanding the recognition for the work done in the household which further conjures double burden especially on working women, is yet to enter the general imagination of the Indian population.

The History and The Underlying Philosophy

With the aims of bringing an inversion in the relations of power, overcoming dependency and a fair redistribution of wealth thus conjured up a Wages for Housework movement across the globe. It was realised that the waged or unwaged women were essentially the same people everywhere, be it India or any other country of the world. However, the movement initially grew from a feminist collective in Italy in 1972. While the movement started as a campaign demanding fair working conditions in the public and domestic realm both, the movement saw the participation of students and activists with direct-action days, protests and workshops.

Since then, it spread to other parts of the world, with increasing emphasis on intersectionality that demanded for greater recognition and wages for household work done by the people with added emotional and physical housework on account of their social positions. In 1975, women in Iceland went on strike from their domestic responsibilities and 1975 was declared as the International Women’s Year by the United Nations.

A number of other autonomous organizations interested in compensation for domestic labour were formed in 1975: Black Women for Wages for Housework, Wages Due Lesbians, the English Collective of Prostitutes (ECP) and some years later WinVisible (women with visible and invisible disabilities). The Wages for Housework Campaign called for a Global Women’s Strike (GWS) on March 8, 2000, demanding among other things, “Payment for all caring work – in wages, pensions, land and other resources.” Women from over 60 countries around the world participated in the protest.

Since 2000 the GWS network has continued the call for a living wage for women and other caregivers, and they have led or joined campaigns focused on pay equity, violence against women, and the rights of sex workers, among other issues. The movement’s impact can be assessed by the legislations and policies that came to be since then, around health care, social security, and reproductive rights, among others.

Also read: Sexism In Economy: Women’s Unpaid Care Work Is Still Not Acknowledged Or Paid

While in India, judiciary has played a crucial role, time to time in initiating certain reforms of the kind mentioned, certain other movements like #MeToo can also be loosely understood with the questions raised through the Wages for Household Movement. However, should one wait for ripening conditions for such a movement in India to be able to capture our imagination? Or should there be a deliberate rallying effort around unpaid household work in forms of protests and awareness workshops by NGOs, activists and other organisations? – is a question one could pose at this juncture.

Featured Image Source: The Nation

About the author(s)

Sana is a research scholar in Political theory, which also happens to be her love of the life. An avid reader, she aspires for a career where she would be paid for reading and reading. With a passion for reading "acknowledgement pages and dedications" by the authors in their books, She hopes to establish an archive of acknowledgement pages one day.