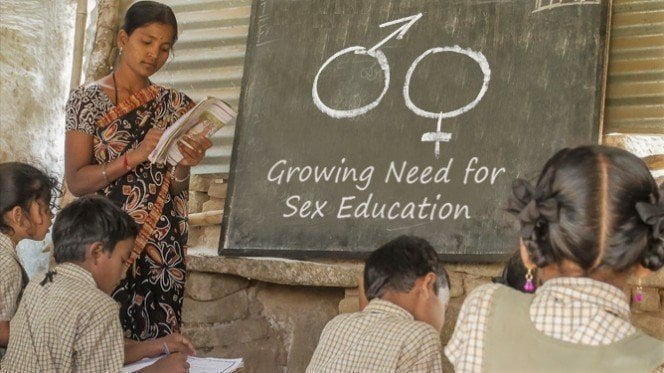

As we welcome the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020, a long-awaited step for years in India, the various strands are being applauded for its flexibility and inclusivity. However, making sexual and reproductive health, sex education and body image an integral part of the curriculum remains widely unattended, yet to be enforced with vigor and involvement of students through a critical lens. How many of us still remember the first lesson on ‘reproductive organs’ back in higher secondary? A topic usually met with embedded stigma, with students looking at each other with different anticipation before the teacher would even begin with it. I’d say most of our discomfort was further added on to by the tearchers’ eagerness to rush through the topic.

As we welcome the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020, a long-awaited step for years in India, the various strands are being applauded for its flexibility and inclusivity. However, making sexual and reproductive health, sex education and body image an integral part of the curriculum remains widely unattended.

Fault In Our Pedagogy: Whom Do We Blame?

The missing link that is the emphasis on sexual and reproductive health is perhaps about the right pedagogy, which cannot be treated in isolation. It is the teachers and students belonging to the same ecosystem we call as ‘society’. Often passing things on to ‘society’, little do we realise we are an equal part of the same society, actively or passively contributing towards perpetuating the status quo we have been grown up with. Recently, I picked up a few NCERT books and revisited the site to check on the official notification on health education and its framework. Commendably, there is an inclusion of topics like the importance of mental health, knowing about your body, sexual harassment, changes in the body, and so on to be taught VII grade onwards, but the implementation and the real discussion of sexual and reproductive health does not exist even in my slightest memory with my teachers. I have learned more about not wearing a short skirt and keeping trimmed nails by my school teachers more than actually learning how to be comfortable in my skin.

Also read: Why Is Sex Or Sexuality Education In Indian Schools Still A Taboo?

Coursework Is Interactive, Not The Minds

Remember, how every chapter in the NCERT textbooks used to have activities written in a colored text box to engage students in activities in concomitant with the concepts learned? However, how many of us remember the teachers actually engaging students in those activities? We continue to follow obsolete pedagogy bifurcating and emphasising on factual learning rather than critical thinking. When students are not assessed or made to write on such crucial issues in examinations, wherein critical learning is not tweaked in any manner, how do we expect them to practice even a modicum of it? Education thus has been reduced to more of a linear space with not a lot of room for introspection and unlearning. Teachers and students are inextricably linked to their conditioned social self, successfully pushing ahead the patriarchal and dogmatic structures in every domain they go.

The Dichotomy Of Public Vs Private: Inveterate Conditioning

When I ventured into two-year-long qualitative research wherein I focused on a group of adolescent girls as my respondents, I tried to unearth their views on how they mirror the body during menstruation and how comfortable they are in practicing hygiene practices for their menses. Not even one of them could answer or openly speak about it. They preferred to say ‘down there’ to denote their genitals with their voice modulation changing in anxiousness and shyness to even say it openly to someone they do not know. Interestingly, they were rebellious about how constricted they feel with the restrictions around menses, but still, none of them dared to question them because they have been edified by their mothers, the latter often symbolised as the paragon of strengthening gendered roles generation to generation. This is the conditioning that most of us grow up with and just a fraction of us who dare to question and debate about them later in life.

Undeniably, sexual and reproductive health, as important as it seems, continues to remain confined in the private sphere of Indian households and is constantly met with shame. It is here we highlight how Paulo Friere has aptly put forward how the ‘culture of silence’ is the pedagogy of the oppressed and the educational system is one of the major enforcers of such problematic silos that needs constant debates to normalize.

What Can We Do?

Going the dutch way

This effectively wouldn’t change unless it is mandated by law to bring about a definite behavioral change in children through learning spaces like schools. It is integral to realise that talking about sexual and reproductive health, and learning about our bodies is as important as coding or a vocational skill that is mandatorily taught to children. To quote an example, the Netherlands follows a thorough sex instruction educational program, educating children as young as four years of age about sex and sexuality. The discussions are not unequivocally about sexual acts yet they spin around affection, regard, and closeness, constructed to acquaint kids with various aspects of sexual well-being. The result? The Netherlands has among the lowest number of teenage pregnancies and sexually transmitted diseases. It is likewise one of the most gender-equal nations.

On the contrary, if we see the American sexual health educational curriculum, it focuses on abstinence and exhibits a scant knowledge on sexual health and the importance of it. The United States struggles to find proper funding and not-for-profit organizations to develop the curriculum on sexual health. Result? America tops in teenage pregnancies and holds one of the highest cases of Sexually Transmitted Diseases (STDs).

Also read: Absence Of Menstrual Hygiene Management In NEP 2020

Engage, Debate, Normalise

Societal-behavioural change when it comes to sexual and reproductive health is indeed a slow process as we talk about challenging a structure in which we have been conditioned since birth, but an arduous effort to legitimise this change at an early age won’t hurt the policy either. Broadly, there are two main steps that can be taken to work on the issue:

- There should be a mandated behavioral science class once a month in schools, where parents, teachers, and children engage, come together, and realise the importance of sexual and reproductive health. Since sexual and reproductive health is largely confined within the four walls of Indian households, it has to be normalised as a part of public debate. The journey hence would begin by involving not just students, but parents too. With the changing times, parents have to be sensitized about the right age to talk about sexual health with children.

- There is a positive increase in not-for-profits developing sexual and reproductive health modules to be imparted in government schools. However it is important that the knowledge be delivered in a impartial manner, otherwise it will not introduce the autonomy and decisiveness in adolescents to make choices about their bodies or physiological self. In fact, delivering such partial knowledge would mean the deliverance of incomplete knowledge and yet again miss on the cord of normalization.

Given the fact that there is a direct correlation of education with behavioral practices, the very root of it has to be addressed by normalising the topic of sexual and reproductive health.

Given the fact that there is a direct correlation of education with behavioral practices, the very root of it has to be addressed by normalising the topic of sexual and reproductive health. Stigma make discussions hermetic and a distant dream to talk about pivotal issues related to one’s own body.

Riya Gupta is working as a Development Consultant in Nutrition with the Tata Trusts. She has done Masters in Social Work in Public Health from TISS, Mumbai. She holds a vehement interest in the Sexual Reproductive Health under which she has worked towards the menstrual health of adolescents, both on-field and research. To envisage a larger change, starting with a smaller one is integral and hence she believes in working with the approach of ‘one step at a time’. Her hobbies including research and writing along with painting and listening to music. She can be found on Linkedin, Instagram and Facebook.

Featured Image Source: Times Of India

This is a very well articulated article. You took me back to class 8 in school and I could completely relate with each and every part wherein you discussed Reproductive Health being practically absent in school education.