Editor’s Note: This month, that is September 2020, FII’s #MoodOfTheMonth is Boys, Men and Masculinities, where we invite various articles to highlight the different experiences of masculinity that manifest themselves in our everyday lives and have either challenged, subverted or even perpetuated traditional forms of ‘manliness’. If you’d like to share your article, email us at pragya@feminisminindia.com.

A man’s essential identity in society is defined as that of a ‘saviour’. If he fails to become that, there is really nothing else, that he can be. As extreme, vague, or absurd as this statement might sound, it is the prevailing crux upon which any notion of manhood is built in a patriarchal society.

Masculinity in popular perception, is constructed as the binary opposite of femininity. Each heteronormative romantic storyline that we come across is structured along this trope. The man’s attractiveness and desirability is established by the fact that he becomes a solution to a crisis.

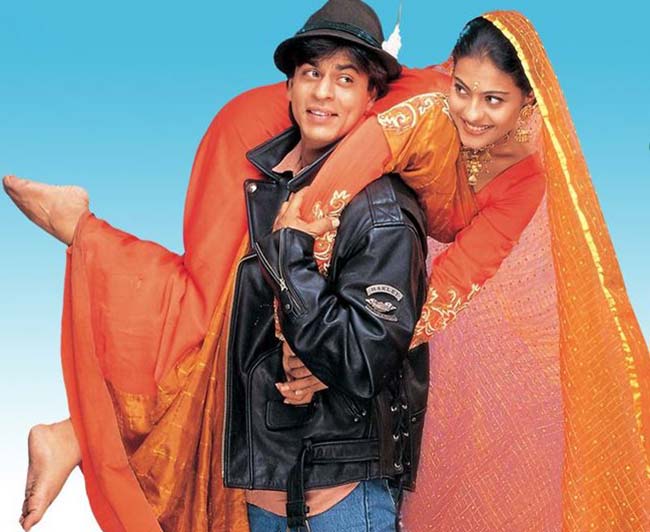

In DDLJ, Raj with his flamboyant and defiant machismo, provides an opportunity to Simran to taste freedom and fulfilment, and escape the conservative social environment in which she is bred. Their love story commences with the hope that he would be able to convince Simran’s family that he is an ideal suitor, and thus ‘rescue’ her from an oppressive, arranged marriage.

This pattern of storyline that was established by this iconic superhit film reverberates and abounds in nearly each film we saw, before and after it.

However, men flexing their muscles and acting as ‘saviours’ is absolutely not a modern trope. It is ancient and timeless. It is so basic and fundamental to our culture and civilisation that if we try to unearth the trope of man as ‘saviour’, our entire worldview of relationships and human life itself would fall apart. Our epics and traditions bolster this idea.

Masculinity in popular perception, is constructed as the binary opposite of femininity. Each heteronormative romantic storyline that we come across is structured along this trope. The man’s attractiveness and desirability is established by the fact that he becomes a solution to a crisis.

Ramayana, the epic that is regarded as an ‘epitome’ of Indian family value-systems and traditions, is entirely structured upon the assumption that the core duty of an ‘ideal man’ is to be able to rescue a civilisation. But the ideal man would not descend from the sky. So, in order to make an artificial notion appear natural and effortless, it begins with the initiation of four tender boys into the Gurukul education system that would teach them essential lessons about life. Foremost of them being the tacit indoctrination that tenderness in a little boy’s psyche is nature’s sin that a patriarchal social order needs to correct.

The gendered ideology of patriarchy reflects in the traditional child-rearing practices that epics like Ramayana and Mahabharata comfortably gloss over. The skills taught to boys and girls were different, and the spaces which they were instructed to inhabit were also different. Boys were pushed to the wildness of the jungle to get habituated to living in arduous physical and psychological conditions, and get over their emotional attachments to any parent or care-giver that would hold them back, from becoming a fighter.

Male nudity in public spaces with costumes like dhotis was so normalised in the traditional learning system that it never occurs to somebody that perhaps not each boy would feel comfortable in revealing his body. Maleness is associated with strength, and this idea is so pervasive and internalised that a boy who feels unable to suppress his emotions or hide away his vulnerability is constantly compelled to feel emasculated by a social order that links ‘maleness’ to stoicism.

This whole idea of considering people who express emotions or vulnerabilities as ‘weak’, itself is deeply problematic. It has been responsible for stigmatisation of mental health concerns, and social norms of masculinity which dictate a boy to adorn a stiff and rigid body-language to exhibit toughness; in contrast to how he really feels about himself, and the resultant body-shaming and bullying that it would lead to, could become the breeding ground for his depression and anxiety and a series of emotional troubles that could haunt him even in his adulthood.

This whole idea of considering people who express emotions or vulnerabilities as ‘weak’, itself is deeply problematic. It has been responsible for stigmatisation of mental health concerns, and social norms of masculinity which dictate a boy to adorn a stiff and rigid body-language to exhibit toughness; in contrast to how he really feels about himself, and the resultant body-shaming and bullying that it would lead to, could become the breeding ground for his depression and anxiety and a series of emotional troubles that could haunt him even in his adulthood.

In Ramayana, the boys are encouraged to let go of their emotional attachments and only focus on cultivating physical and mental strength, perseverance and tenacity within themselves. There is a dialogue where one of the brothers tells the mothers that according to his mentor, a man’s core competency lies in his bravery, with which he can become able to save the world.

You would probably not find anything outrightly problematic with this statement.

Even I did not. Throughout my childhood, while watching daily soaps and fiction on television where the masculinity of the male character essentially resided in becoming an answer to each obstacle that the woman faced in her life, I did not often consider the possibility that as a boy, I am constantly feeling insecure about the fact that my individuality is not conforming to the notion of masculinity that society has glorified and put on a pedestal.

When I had a bad day at school (and there were many) or days when I felt low, I used to feel this pinching realisation that my sadness, or anxiety would always feel absurd or misfit to the ways of this world, that has sanctioned only one kind of emotional response for men: anger. There are countless number of films and serials built on the good guy v/s bad guy trope. Where the difference between the two essentially is that the bad guy uses his aggression to cause harm to society, and the good guy is busy rescuing the world or his heroine, from the advances of the bad guy. The underlying similarity between the two is that they both manifest aggression and physical strength, albeit in different ways.

The good guy appears gentle but his masculinity is established by the fact that he can fight off and resist, and by the fact that he brushes all possible sources of conflicts and pain aside, because trauma cannot essentially touch a man, and the rare moments when it does, his classic response becomes to emerge as a ‘man’ and fight it off with his strength and determination.

How often have you seen a boy getting consumed by his trauma and become actually helpless and fragile?

It nearly never happens in the stories you read or watch, because masculinity is a performance. You brutally convince a boy that by the time he achieves puberty, he has to become adept at the task of hiding his feelings, because they become a cause of his internalised shame. That, if he can’t fight it off with grit and determination, he should learn to submerge it within such deep corners of his brain and heart, from where it would never again be accessible. This pattern of representation that socialises men and boys to privilege reason over emotion, and keep their emotional instincts in check is suffocating.

There are countless number of films and serials built on the good guy v/s bad guy trope. Where the difference between the two essentially is that the bad guy uses his aggression to cause harm to society, and the good guy is busy rescuing the world or his heroine, from the advances of the bad guy. The underlying similarity between the two is that they both manifest aggression and physical strength, albeit in different ways.

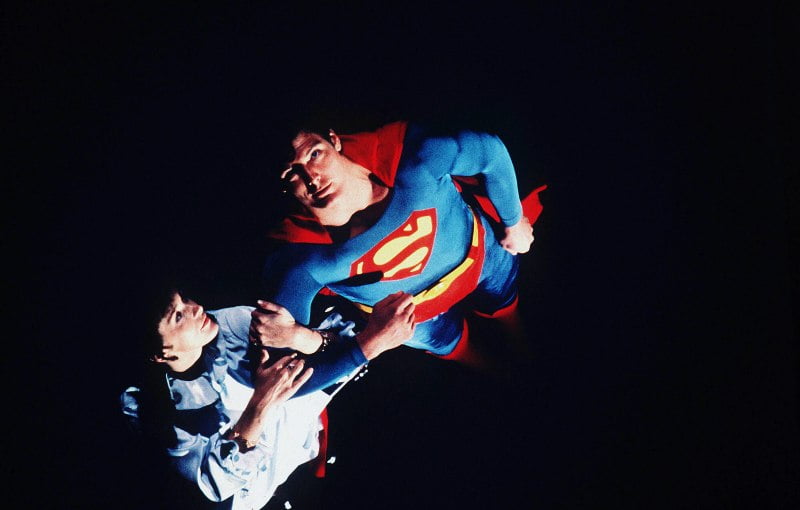

The saviour syndrome in boys is a real thing, and it is brutally manufactured and superimposed by the media. All your comic books that feature superheroes are too busy saving the world. They are perpetually telling a boy that he must never feel that he too at times needs to be saved by somebody. Rather, he must always relish his own imagined ability to save the world.

Do these superheroes never break down?

Perhaps they do (I wouldn’t know, because I sadly never bothered to participate in the obsession), but they are still built in the mould of hegemonic masculinity that privileges reason over emotion, and plays its part in strengthening the stereotype prevalent in pop-culture, according to which; nervousness, anxiety, hysteria, self-doubt or any other kind of prevailing emotional trouble appears as an inherently ‘feminine’ trait, which inevitably follows to suggest that trauma, depression or anxiety in a boy would invariably make him less of a man.

Also read: A Feminist Approach To Masculinity: How Schools Impose Binaries

In our obsession to glorify male courage and perfection, have we erased culturally available means and vocabulary to express male vulnerability so effectively, that even when it is visible, it is not seen?

Men acting as ‘saviours’ in real-life or fiction is not so much a problem, as much as the fact that the role of the saviour is so normalised, and rather essentialised that boys who find themselves unable to relate to the mould of hegemonic masculinity land up in an identity-crisis, because there are just no alternate culturally available ways to become a man in this society.

When I was growing up, I used to find it next to impossible to tell people or even realise for myself, that my experience of being bullied in childhood perpetually kills off my self-esteem despite the best of my efforts to curb my anxieties. Merely the thought of referring to my past memories used to inflict a lot of shame upon me, and I felt that I would rather cringe from within and bury my shame, than reveal the truth that I feel scared and fragile in front of the world. For boys, by the time they are fourteen, are supposed to become manly in their persona, and manliness has been culturally defined as a state of mind and personality that is devoid of fear.

I was afraid of admitting that I felt scared of stepping on the roads, or traveling in public transport. That I am a slow learner and I take time to get used to any new surroundings. According to the public eye, I was a man and embracing the public space was supposed to be my birth-right. What could possibly stop me from exercising that?

Men acting as ‘saviours’ in real-life or fiction is not so much a problem, as much as the fact that the role of the saviour is so normalised, and rather essentialised that boys who find themselves unable to relate to the mould of hegemonic masculinity land up in an identity-crisis, because there are just no alternate culturally available ways to become a man in this society.

I always believed that I am too sophisticated to believe in regressive and limited conceptions of manhood, but when I started having recurrent pangs of anxiety, and was compelled to finally admit to myself that I have been living with depression since a long time, I felt that it never mattered what my own views about myself were. As much as I took pride in being different from others, I had somehow internalised the belief that the tall, scary, rugged, athletic guy who subconsciously intimidates me in a teen drama, box office hit or in a real-life campus setting, is more of a man than I could ever be.

Also read: PUBG And The Glorification Of A Hyper-Toxic-Masculinity

That if I am not a saviour in a relationship, there is little else that I can be.

You can have your own set of beliefs about everything, but society and media would still manage to emasculate you.

Featured Image Source: Feminism In India

About the author(s)

Bhaskar Choudhary has recently completed Young India Fellowship, and is pursuing a postgraduate liberal arts diploma from Ashoka University. He has also done Bachelor in Arts from Jai Hind College, Mumbai with a Psychology major, and minor in English Literature and Political Science. He loves reading literary classics. His favourites are 'Great Expectations' and 'Wuthering Heights'.