“With tears in his eyes and a cracking voice he recounted how, when he first picked up the bucket and cleaned a dry latrine, all he could see were books in front of his eyes and his head began to spin.” – This is the testimony of a boy who began manual scavenging at the age of 17.

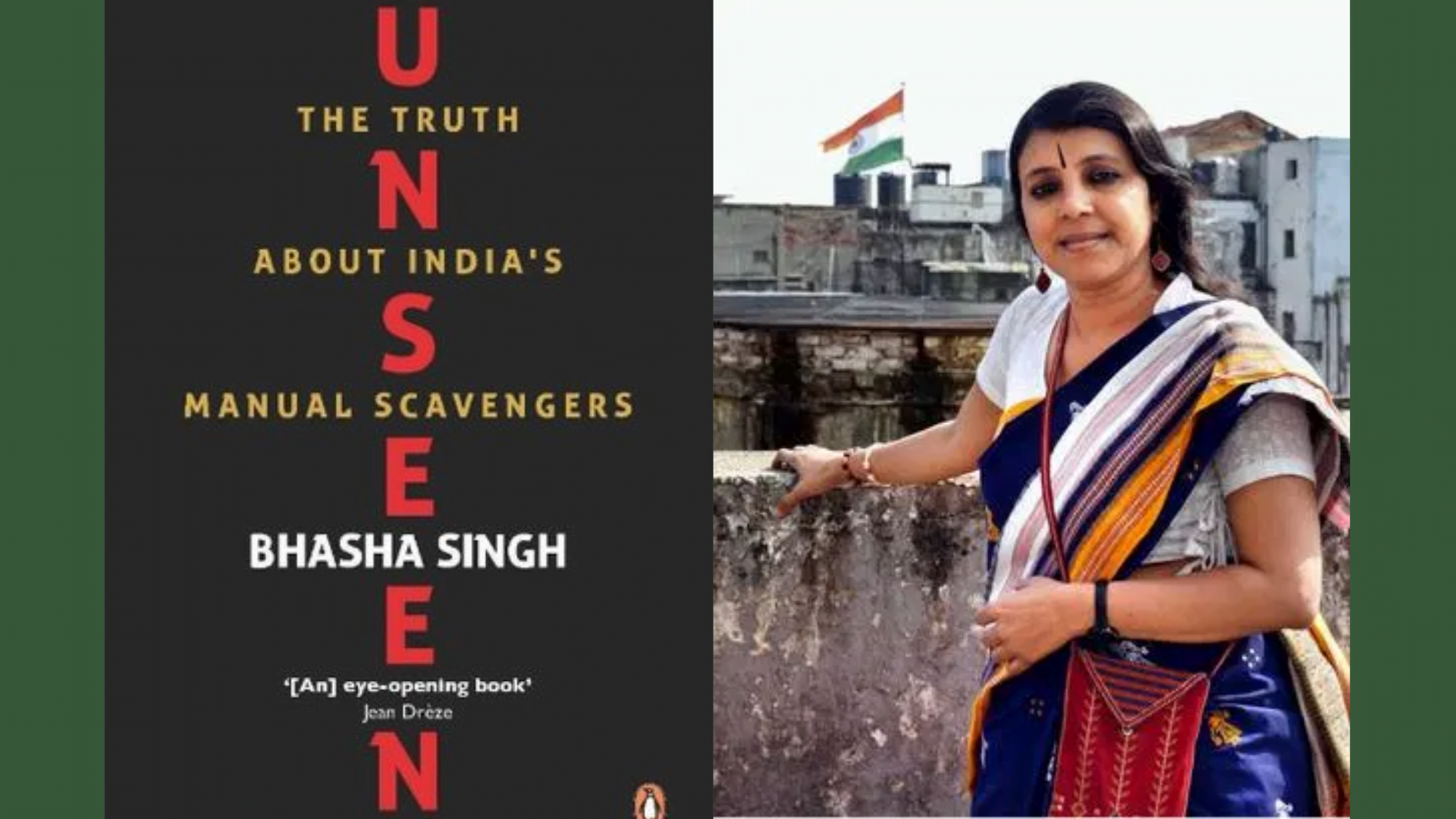

Bhasha Singh’s book ‘Unseen: The Truth about India’s Manual Scavengers’, awakens the reader to a world of a powerless community born to mankind but reduced in spirit to an invisible ‘shit-picking race’. The entire book has been organised around the author’s central thrust at unravelling the exploitative and feudalist forces which, according to her, have been rooted in the caste system, patriarchal social order, ineffective legislative, executive and judicial machinery, ignorant policy making and unconcerned politicians.

Bhasha Singh’s book ‘Unseen: The Truth about India’s Manual Scavengers’, awakens the reader to a world of a powerless community born to mankind but reduced in spirit to an invisible ‘shit-picking race’.

In Bhasha Singh’s journey across Indian states in pursuit of documenting the testimonies, and experiences of manual scavengers and visiting their houses and workplaces, she seems to have donned their shoes, and felt their rage and hopelessness and poured it all out in her writing. To substantiate her critical lens towards the socio-political structure and institutions sustaining this inhuman practice, Bhasha Singh has presented compelling arguments and evidence from government reports, political statements, testimonies from the scavengers as well as members of NGOs like the Safai Karamchari Abhiyan (SFA) and Garima Abhiyan, and her own chilling experiences as a ‘manual scavenging journalist’.

Bhasha Singh’s book progresses in the form of a narration and engaging dialogues addressing the most basic questions at the root of this practice, like-“Why don’t people leave this work?” or “Why, despite it being illegal, have governments allowed this practice to continue?”. In the first part of the book, Bhasha Singh presents many dimensions of the life and struggles of the manual scavengers. She has clearly justified the title of her book by narrating the pangs of discrimination faced by these women in domestic and public spaces, the treatment of ‘Valmiki’ children as untouchables and forcing them to clean toilets in schools or sit at the back of the class. Bhasha Singh has also reflected on how the terminologies such as ‘Dabbu-wali’, ‘Balti-wali’, ‘Tina-wali’, ‘Tokri-wali’ used for these women represent that their individual identities have been subsumed by a caste identity recognised as the untouchables of the society. The book also brings to the fore a gendered dimension to this profession.

Bhasha Singh reiterates, “Women are Dalit among Dalits”. Although this gendered aspect can be found in other works, what is unique to Bhasha’s story is her focus on documenting the aspirations, hopes and dreams of these women who fiercely argue that they won’t let their daughters follow in their steps. It talks about the day to day culture and habits of people from this community. How they dress, what they eat, and the content of evening conversations, something that does not find mention in literature on manual scavenging. Bhasha Singh’s focus on the ‘personal’ in her book presents a humane representation of an otherwise invisibilised community.

Also read: In Conversation With Bezwada Wilson: The Fight Against Manual Scavenging

A striking element in the book are the stories of female manual scavengers rising as local Dalit leaders, however, Bhasha Singh writes that their representation is yet to find voice in upper rungs of politics. Along with representing these struggles, the author has tried to document the different strategies of protests employed by this community and other civil society initiatives, for instance the independence day march by manual scavengers marking the manual scavenger’s day in Gujarat, otherwise, claimed as a ‘Nirmala Pradesh’ i.e. manual scavenging free state.

Bhasha Singh has further criticised the Employment of Manual Scavengers and Construction of Dry Latrines (Prohibition) Act, 1993 for its inherently flawed provisions that practically give way to propelling rather than eradicating this practice. While caste stigma has kept them out of alternative professions, the government assistance in terms of loans has been viewed as hollow aid. In understanding the roots of the problem, Bhasha Singh has also thrown light on the gaps in the country’s sanitation infrastructure: from areas still without sewers, and poverty stricken localities with dry latrines to the lagging installation of bio toilets in Indian Railways.

Although one can upbraid the author’s arguments for being highly skewed against the statutory acts and government’s actions, however, the evidences presented by Bhasha Singh in the form of survey reports, research data, and the lack of intervention to provide alternative solutions blow the gaff on ‘closed door’ politics of the officials and parties in power. Her book thus presents itself as a brute challenge in the face of lies painted through false claims, and the flawed surveys and reports denying the prevalence of this practice. A major limitation of the book however, in my perspective, is the attention not placed on exploring the stories of manual scavengers who have already shifted to a new profession. This could have been of valuable insight to policy makers as well as human rights activities and civil society organisations in learning about the strategies through which these communities can be empowered.

While an academician will find Bhasha Singh’s book useful in understanding the contrasts and similarities in the intricacies of the dynamics of caste system, gender bias and politics that play out differently in different states to create new forms of structural violence and institutional channels of subjugation of generations of one people in one filthy dehumanising profession. For policy makers willing to bring change, this book gives an insight on the aspects that actually need intervention through targeted policies to help eradicate this practice from its very roots as well as enable the rehabilitation of these people. As for the general public, the book is a crucial eye-opener presenting a reality check on the continued existence of untouchability, and exploitation of children and women even after 74 years of Independence.

Bhasha Singh’s unfaltering criticism of the government’s apathy casts it as an oppressor furthering caste discrimination and violating the most basic human rights. It also repeatedly hints at a social order bereft of empathy and concern for the manual scavengers.

Also read: Divya Bharathi’s ‘Kakkoos’ And The Casteist Reality Of Manual Scavenging

The book throws the reader in a state of mind where it is nearly impossible to conceive of any rapprochement between the manual scavenging community and the rest of the world. Bhasha Singh’s unfaltering criticism of the government’s apathy casts it as an oppressor furthering caste discrimination and violating the most basic human rights. It also repeatedly hints at a social order bereft of empathy and concern for the manual scavengers. This book is thereby a significant awakening about the truth of manual scavengers entangled in a vicious circle of exploitation, indignity and subjugation.

Ambika Singh is an undergraduate student in her third year, pursuing B.A. (Hons.) Political Science from the University of Delhi. She can be found on Twitter, Instagram and LinkedIn.