The news of a manager of a government-aided shelter home, run by an NGO in Bilaspur, Chhattisgarh, allegedly sexually assaulting three women residents, including a 20-year-old, made it to the margins of the mainstream news on January 21 this year. The women accused the staff of the NGO Shiv Mangal Shikshan Samiti of beating up and abusing the 20-year-old, while she begged to let go of her 8-month-old daughter. This case has highlighted the exploitative conditions that continue to prevail in several women’s shelters, and the immediate need of media and government attention required for these spaces, originally and ironically meant for women’s rehabilitation and re-integration.

This case highlighted the exploitative conditions that continue to prevail in several women’s shelters, and the immediate need of media and government attention required for these spaces, originally and ironically meant for women’s rehabilitation and re-integration.

The 20-year-old woman narrated that on the evening of January 16, about three kilometres from home, she was approached by an elderly man, who saw her crying, and called someone. Soon, a staffer from the Ujjawala shelter home came and picked her up. She was not allowed to leave the next morning. She was kept with two other women, all of whom were physically and mentally harassed. They also alleged that they were stripped, drugged and locked up.

The shelter was set up as a part of the Ujjawala Scheme by the Ministry of Women and Child Development, a scheme initiated for the prevention of trafficking and rescue, rehabilitation and re-integration of victims of trafficking for commercial sexual exploitation.

This case, just like the many others that must have skipped public attention, begs the urgent need to look within shelters and determine the quality of life of the residents. In 2018, in Muzzafarpur, Bihar, in a shelter home run by an NGO called Sewa Sankalp Evam Vikas Samiti, 34 out of 42 women were sexually abused. Last year in Kanpur, 171 girls reportedly shared 100 beds at a shelter home. Out of them, 57 were found COVID-positive, and 7 minors were pregnant.

Also read: Covid-19: Why Are Women More Vulnerable To Mental Health Issues?

These cases highlight the need for immediate intervention within these homes, to be able to provide safe living conditions for violence survivors. With this aim, the Lam-Lynti Chittara Neralau, or LCN Network was formed. It is a network of over 50 organizations and individuals focused at working towards accessible and safe shelters to survivors in need.

They have been conducting research to foreground the experiences and voices of women survivors. A synthesis of their key findings, namely ‘Survivor Speak’ outlines that it is extremely difficult for researchers and social workers to access shelters. Survivors interviewed had poor knowledge about their rights. There were also concerns regarding quality of life within shelters, as shelters had poor infrastructure, lack of privacy and enabled little mobility outside. Many survivors encountered offensive and discriminatory behaviour by shelter staff and felt disempowered. The shelter managers had limited knowledge of women’s rights and thus presented quite a problematic and patriarchal view of survivors of violence, sexual orientation, etc.

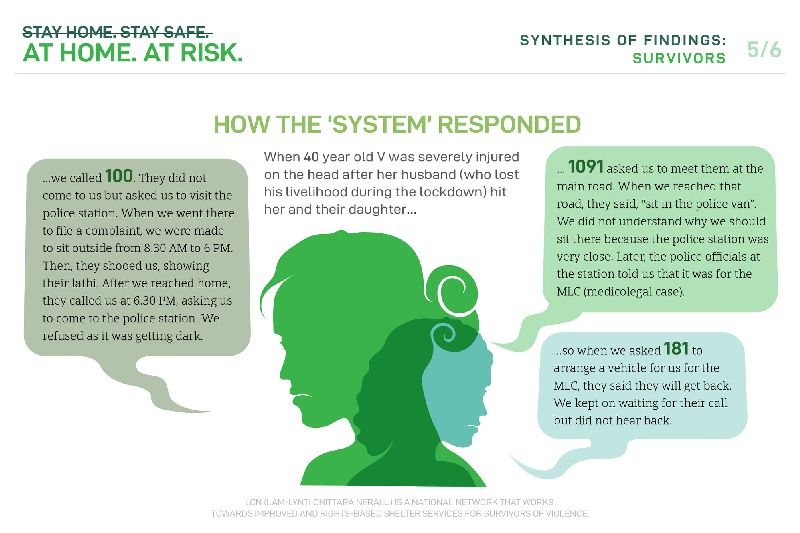

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown only heightened the vulnerability of women and girls: including trans persons, elderly women, and women with disabilities facing domestic violence. It exposed gaps in support and redressal mechanisms that had already been failing its beneficiaries for long; and the few that were responsive were redirected towards COVID-19 emergencies and managing the lockdown. In order to understand the impact of the pandemic and lockdown on access to services for survivors of domestic violence, LCN conducted a series of rapid surveys in 2020.

The study revealed several challenges that survivors and stakeholders had to face during the lockdown. Survivors had little awareness about helplines, and low access to technology. Therefore, it was difficult for them to access relief measures. Some who had access to phones reported lack of privacy to make the call for help. Mobility was severely restricted, and many found themselves trapped with their abusers as they were unable to travel to police stations, hospitals or shelters. Others reported that even when they were able to, they were met with no response.

Also read: Let’s Talk About Domestic Abuse During COVID-19

The study also recommended diligent mechanisms for monitoring and evaluation of shelter homes including conduct of periodic social audits and setting up of Advisory Committees with members of rights’ based NGOs, women’s groups for enhanced transparency and effective functioning.

The study also recommended diligent mechanisms for monitoring and evaluation of shelter homes including conduct of periodic social audits and setting up of Advisory Committees with members of rights’ based NGOs, women’s groups for enhanced transparency and effective functioning.

One of the learnings from the research was that, though there has been an increased focus on gender-based violence, and more specifically, domestic violence during the lockdown, one important link has mostly been kept out of it. The conversation on shelter homes is usually missing from larger conversations of addressing gender-based violence. Safe shelters help women say NO to violence; ideally, they are crucial support structures that bolster her on her journey as a survivor. Hence, shelter homes find their mention in the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005.

The Bilaspur case has thrown light on the gap between the letter of the law and it’s implementation, especially when it comes to survivors of violence. There must be transparent accountability mechanisms that oversee the shelters with respect to their functioning. Lastly, there must be greater interest in shelters by women’s rights groups, researchers, NGOs and the issues around them must be integrated with the larger issue of addressing violence against women, and ensure a rights-based support system for women and girls.

Aanchal Seema Khulbe is a researcher, activist, social worker, feminist and flawed. She can be found on Instagram, Facebook and Twitter.

Featured image source: Scroll.in