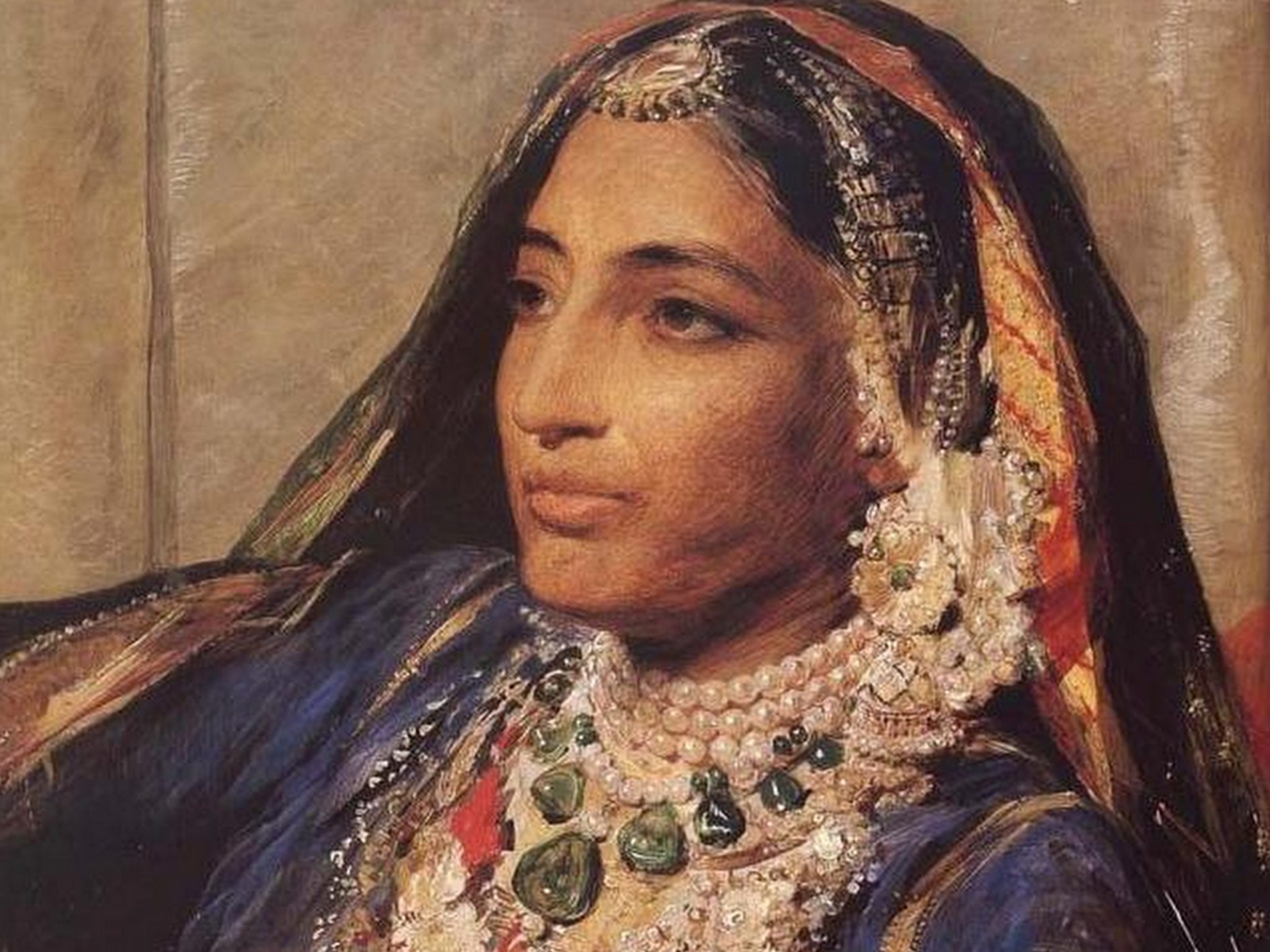

A historical novel is bound to begin with preconceptions based on known and circulated history. However, what is known can never be absolute because, like every story, history is a perspective, a story told by a story-teller. Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni uses Chinua Achebe to hint at this understanding of perspective when she begins the story of Rani Jindan Kaur in The Last Queen.

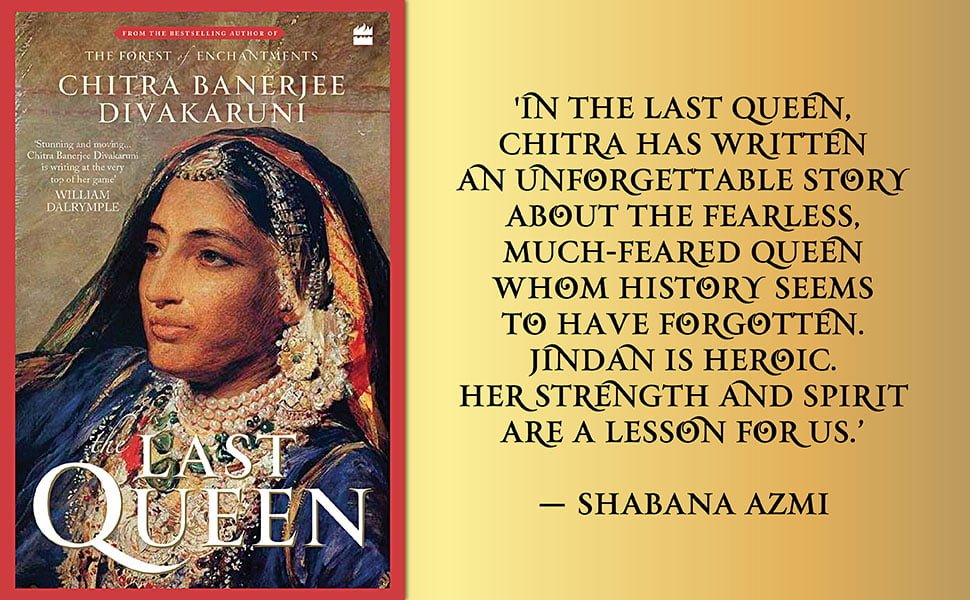

The Last Queen

Author: Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni

Publisher: HarperCollins Publishers India, 20 January 2020

Genre: Historical fiction

The tale of a woman told by a woman enlivens the vastly unknown story of Jindan by intriguingly blending fact and fiction into an unputdownable novel, The Last Queen, which narrates the journey of a simple village girl to becoming the last queen of Maharaja Ranjit Singh.

The tale of a woman told by a woman enlivens the vastly unknown story of Jindan by intriguingly blending fact and fiction into an unputdownable novel, The Last Queen.

Stopping by the contents, the reader can notice a spread of four broad sections – ‘Girl’, ‘Bride’, ‘Queen’, ‘Rebel’ – in a bildungsroman style, narrating a tale of growth. The story is intricately woven around moments – ‘Guava’, ‘Horse’, ‘Wedding’, ‘Deception’, spaces – ‘Hovel’, ‘Shalimar’, ‘Zenana’, places- ‘Jammu’, ‘Kathmandu’, ’Calcutta’, ‘England’ – which consequently bear traces of mounting complications in the life of the girl who becomes a rebel.

It intrigues the reading mind- what took Jindan halfway across the world? The simple but arresting narrative builds up at a comfortable pace, picturesquely describing Jindan’s life – her girly adventures in the village, her entry into the charismatic city of Lahore, her meeting with the Sarkar, her desperation in love, her exploits of the queenly life, her son, her powerful hatred for the colonisers.

The narrative allows the reader to sink into its simplicity, without ever distancing her with dazzling glamour of a regal life. As the narrative steps in its earthly smell, it allows its characters to be realistically grounded, who consequently become convincing and identifiable.

Also read: Book Review: Dewaji—Making Of An Ambedkarite Family By Dipankar Kamble

The story begins at the death bed of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, where Jindan, the young Queen mother, is haplessly witnessing the future of her life slipping away. The daughter of the royal dog keeper, her lowly birth was not a match to the high status of the Sarkar; however, she was his ‘last’ queen, a favourite by dint of a strong sense of individuality mixed with an acute sense of independence, fearlessness, comingling of the emotional with the pragmatic.

The strength of her bond with the Maharaja emanated from a shared love for simplicity. Her story is not the usual rags to riches story, because, while the rags never brought discomfort in a life that wanted little joys, like reading books, reaching for the riches was never her ambition. She was in love with a man, and the man was coincidentally the king of Punjab.

Her sense of freedom is most palpable in the first section of the novel – ‘Girl’, which opens in her small disheveled hut at Gunjranwala. She wants to be a ‘provider rather than being a mouth to feed’. The first person narrative from now on allows the reader to navigate the alleys and sidewalks of a stronger, intelligent, brave, impudent woman, almost other-ing her from convenient womanhood of the period. In fact the entire novel stands as an alibi to her strangeness, her defiance which makes her both human and phenomenal, carving her name in history.

The simple, but racing love story of the first section paces down significantly in the second – ‘Bride’, where the politics of the country finds a crude ally in the politics within the zenana – the women’s sphere of the royal household that teems with wives and concubines of Ranjit Singh. While a formidable sense of danger lurks at every corner of the zenana, the charm of romance between the Sarkar and Jindan has soothing effects.

Also read: Book Review: Hindutva And Dalits—Perspectives For Understanding Communal Praxis

The life of a queen is not a fairytale; it’s a life of sacrifice – Jindan is reminded by Fakir whenever she complains. She is quick to learn courtly manners, but does not care to fit in anywhere, except in Sarkar’s heart. He is her solace, as is Punjab, her motherland. But when she loses Sarkar, she is quick to access the foreboding danger and manipulates Dhyan Singh to help her flee to Jammu with Dalip, her infant son, and Mangla, her trusted maid.

When ‘Queen’ opens Jindan is riding Toofani amidst the blue shades of Jammu hills. Although her boisterousness seems mellowed in exile, she still likes speed. Confined to a golden cage, her only solace is her growing son, her trusted maid, and Fakir’s letters which bring her comfort and counsel. She is terrified by the political conspiracies raging in Lahore and wishes to stay away. But she is forced to return soon and pulled into the vortex of intrigues, murders and betrayals.

The first person narrative from now on allows the reader to navigate the alleys and sidewalks of a stronger, intelligent, brave, impudent woman, almost other-ing her from convenient womanhood of the period.

In such a treacherous atmosphere, five-year-old Dalip ascends the throne of Punjab, and Jindan becomes Mai Jindan, mother of Punjab. However, the narrative never loses sight of the humane Jindan who encounters an unprecedented tussle in her life as Queen Regent, a mother, the widow of a great king, and a young woman who is yearning for love.

Fearless and unconventional, she listens to the call of love, tears herself from her crying child at night to meet her lover, speaks explicitly to her dear ones of her womanly desires, bravely bears an abortion and unveils her pox-marked face to ensure her fidelity to her kingdom. But she falters to subdue her ego, loses her visionary sense, pushes her Khalsa army into a self-defeating fight against the British, and loses her all. Separated from her son by the conspiring British, she reaches Nepal to seek both asylum and rest in order to prepare herself to strike harder.

In ‘Rebel’ we find the rootless queen longing for her roots, her country, her independence. She meets her son, chooses motherhood as her sacred love, and then longs for a return. It is only when she commingles her love for her country with the love for her son that she decides she must bring him to his mother, to his motherland. This section, seeped in nationalist fervour, aptly paints Jindan’s efforts in bringing Dalip back to his roots. Her uncompromising attitudes, even at the face of vicissitudes in life, makes Dalip wonder and question himself, encouraging him to look beyond.

Also read: Book Review: Why I Am Not A Hindu Woman By Wandana Sonalkar

Divakaruni’s blends in Jindan the attributes of a girl-next-door and a magnanimous queen who is rooted, intelligent, beautiful, feisty, who bows to no external force but her passionate love for her dear ones and her Punjab. As the writer and the reader engage in dynamically creating Jindan, she might seem unimpressive to the modern woman whose awareness of her rights and dealings is acute and almost normalised. But to realise that we bear the legacy of a mid-nineteenth century independent spirit might allow us to contemplate the many Jindans who questioned conventions and unregrettably lived a life they chose, making us aware of possibilities today.

Divakaruni deftly weaves Jindan’s life with earthliness that allows the reader to befriend Jindan empathetically. Her life bears witness to the fact that being a feminist is a way of life and Jindan can be every woman, while also being outside the lot. This simple narrative of a woman, who dreams, believes, achieves, falters, loses, but never allows life to dictate her, points at what we have inherited, and must propagate sensitively – a strategic commingling of compliance and contestation, setting the rules of the game by playing it.

Featured Image Source: BritAsiaTV

About the author(s)

Priyanka Chatterjee is a mother, researcher, and academic. She lives and writes from Siliguri. Her articles have appeared in Feminism in India, LiveWire, Himal Southasian, Sikkim Express, among others. She can be reached at site.surferpc@gmail.com and is on Instagram @priz_chatt