Nationalism in modern nations has often been imagined through gendered metaphors, especially those involving the female body or those evoking the mother figure, a phenomenon that has poignantly shaped national identities. In India, this was found in the anthropological and cartographical rendition of Bharat Mata, whose iconography brought both the female body and mother figure together, moreover revealing the roles of and expectations from an Indian woman. Bharat Mata became the most iconic image for the nationalist agenda, and was fiercely propagated to evoke popular imagination about Independence and subsequently, the free nation.

A construction of femininity

The late 19th century saw a new construction of the woman by the British, based on modernisation practices upheld through a disdain for practices like sati, purdah and child marriage. Indian reformers and nationalist leaders were eager to adapt to these western ideals while retaining a certain ‘Indianness’, possible only by ensuring that these novel freedoms for the ‘new woman’ were exercised with submissiveness, restricted by traditional patriarchal frameworks. Secondly, femininity was imagined in a manner that would enhance the masculinity of Indian men, given the effeminate jibes thrown at the latter by the British; devoted and domesticated, Sita and Savitri were epitomised as ideals of womanhood.

Furthermore, motherhood, an ideal deified in Indian tradition, had to be reasserted given the British scepticism; nationalists proclaimed mattabhav as the ultimate female quality that would guide the future citizens of India.

“The ideology of motherhood could be specifically claimed as their own by the colonised and could help in emphasising their selfhood.”

In the 20th century, the ideal of silent suffering, associated with women, was hailed by Gandhi as the basis of non-violence. Furthermore, the concept of motherhood was elaborated to signify the mother as the ‘defender of civilisation’, prompting significance to the idea of a united motherland. Bharat Mata, aligning the duties of a woman with that of a mother; it additionally aroused nationalist sentiment as “the mother, when in danger, could summon her ‘countless’ children to her aid.”

The concept of motherhood was elaborated to signify the mother as the ‘defender of civilisation’, prompting significance to the idea of a united motherland. Bharat Mata, aligning the duties of a woman with that of a mother; it additionally aroused nationalist sentiment as “the mother, when in danger, could summon her ‘countless’ children to her aid.”

Also read: Bharat Mata and the Ideal Indian Woman

Iconographic miscellany

Bharat Mata was invoked through poetry, literature and, later, movies, and was alternatively projected either as a beautiful weeping woman or as a woman holding a staff, like a trident, inspiring her children to act. For instance, in Bengal, Bharat Mata was imagined as a manifestation of shakti, as the powerful Maa Kali or Durga; she was accorded the status of a cultural artefact that could both be represented as powerful and frail, depending on the situation. For Hindu right organisations like the Sevika Samiti and Durga Vahini, which sought to create a military cadre of empowered women, ‘empowerment’ was situated within a lineage of mother goddesses, especially Bharat Mata, who was invoked in the name of the nation and the awakened Hindu woman.

Bharat Mata, 1905, Gouache and wash on paper by Abanindranath Tagore, Coll. Rabindra Bharati, Kolkata.

Source: Sen, Geeti. “Iconising The Nation: political agendas.” India International Centre Quaterly 29 (2003): 154-175.

One of the most popular renditions of the Bharat Mata was by Abanindranath Tagore, who equated ideal Indian womanhood with representations of stoicism and self-sacrifice, romantic bereavement and suffering. Tagore’s painting came to be seen as an icon of swadeshi and the spirit of the motherland. In contrast to the popular idea of shakti, Tagore’s painting was “yogic and contemplative…set apart from the common world.” The figure was disengaged from corporeality, with her breasts and hips unobtrusive, and the use of wash technique that snatched away traces of the body mass. She was seen holding the objects of nationalist goals – food, clothing, secular knowledge and spiritual consciousness.

Following Tagore, however, representations of the Bharat Mata moved out of the mould of the aesthetic icon of his rendition, and entered the field of calendar art, and were popularly reproduced and widely circulated by shopkeepers. By the 1920s and 30s, artists like M.V. Dhurandhar were creating deified figures of the Bharat Mata alongside images of national heroes or symbols of prosperity like the charkhas, railways, etc. These changing notions of femininity resulted in this female figure playing the dual role of acting as a metaphor for a sacred space, shielded from western contamination, as well as a symbol of the motherland.

Also read: Ayodhya Issue Reflects The Increasing Masculinisation of Politics In India

In the cartographic realm

Overtime, Bharat Mata came to be associated with maps and it is interesting to note how this iconography negotiated the idea of space to provide an outlet for male devotion towards the nation. These maps transcended the basic purpose of defining physical territory, at times even disregarding the proper national boundaries, and became more humanised places that brought together poetic, religious and nationalist imaginations to inspire action. Geographical knowledge had been one of the major concerns of the colonial officials as consciousness was imparted through maps and globes introduced into education to impress into the natives a sense of their territory. The Bharat Mata maps stood quite in opposition to such scientific maps, which as Brian Harley argues, dehumanised territory, making it unfamiliar.

Made by citizen-subjects, rather than the state, these anthropological maps, on the one hand, articulated a language of protest against colonial maps and on the other, personalised the nation-space by inserting the image of a familiar goddess. Deified as a goddess of polity and territory, cartographic representations of Bharat Mata became a common visual in protest paraphernalia, banners, logos, and books, both regional and English, bridging a very intimate relationship between the map and the mother. The maps existed to convert the neutral citizen into a devoted patriot, who was willing to give his life for the nationalist cause; they transformed the dead space of the scientific map to a homeland and motherland.

Shaheed Bhagat Singh (Martyr Bhagat Singh), artist not known, late 1940s, Chromolithograph published by Rising Art Cottage, Calcutta, Courtesy of Christopher Pinney, Cambridge. Source: Ramaswamy, Sumathi. “Maps, Mother/Goddesses, and Martyrdom in Modern India.” The Journal of Asian Studies 67 (2008): 819-853.

A chromolithograph from the 1940s shows a young Bhagat Singh offering his severed head to a flag-bearing Bharat Mata, who blesses him for his corporeal sacrifice, as his blood flows onto the globe, in a clear sign of obeisance and patriotism. Imagery like this was widely reproduced throughout the years of nationalist struggle and after to instill in people a devotion for their nation. Furthermore, the sari symbolised a true Indianness, as well as the unfair relationship between the nation and colonial state, on the issues of drain of wealth and textile dumping from British industries; the sari was also a call to hark back to Indian products.

Bharat Mata maps helped reimagine the national territory, with her billowing sari constructively used to reclaim national space; the contours of her body reflected the geographical outline of India, to such an extent that the map was often not required as a prop for her identity. The clothing, jewellery and posture pointed to a certain antiquity, in a sense invoking the timelessness of the nation. The use of the female body is also significant as it allowed male fighters to view territory as a vulnerable woman, and a mother, who had to be protected.

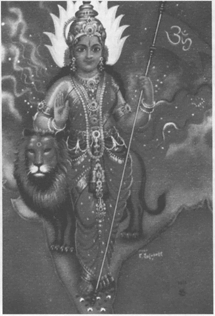

Bharat Mata, 1997, Poster by E. Jesudass, Published by SPP Delhi, Coll. J.S, and Patricia Uberoi, Photo Courtesy: Patricia U. Source: Sen, Geeti. “Iconising The Nation: political agendas.” India International Centre Quaterly 29 (2003): 154-175.

A poster from the late 1990s depicts Bharat Mata as a Hindu goddess with the background of the India map. Interestingly, it also reflects a certain anxiety over political borders that had started building in the face of independence and has continued ever since, renewed by Hindutva politics from the 1980s.

Unsurprisingly, Bharat Mata iconography has now transcended the nationalist era. A poster from the late 1990s depicts Bharat Mata as a Hindu goddess with the background of the India map. Interestingly, it also reflects a certain anxiety over political borders that had started building in the face of independence and has continued ever since, renewed by Hindutva politics from the 1980s. The equation of the identity of the nation with the devotion to Bharat Mata is most apparent in the Bharat Mata temple at Banaras, which houses an elaborate marble map of India in the centre, transposing the mother goddess onto the geographical entity of the nation. Bharat Mata has, in every essence, become the iconic metaphor for the nation; from a literary abstraction, she has transformed into a familiar figure of nationhood, meant to be deified and protected.

References

Dinkar, Niharika. “Masculine Regeneration and the Attenuated Body in the Early Works of Nandalal Bose.” Oxford Art Journal 33 (2010): 169-188. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40856513.

Guha-Thakurta, Tapati. “Women as ‘Calendar Art’ Icons: Emergence of Pictorial Stereotype in Colonial India.” Economic and Political Weekly 26 (1991): 91-99. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4398221.

Gupta, Charu. “The Icon of Mother in Late Colonial North India: ‘Bharat Mata’, ‘Matri Bhasha’ and ‘GauMata’.” Economic and Political Weekly 36 (2001): 4291-4299. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4411354.

Maxwell, Rebecca. “Maps as People: Anthropomorphic Maps.” Last modified February 20, 2014. https://www.geolounge.com/maps-people-anthropomorphic-maps/.

Sen, Geeti. “Iconising The Nation: political agendas.” India International Centre Quaterly 29 (2003): 154-175. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23005824.

Sethi, Manisha. “Avenging Angels and Nurturing Mothers: Women in Hindu Nationalism.” Economic and Political Weekly 37 (2002): 1545-1552. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4412016.

Thapar, Suruchi. “Women as Activists; Women as Symbols: A Study of the Indian Nationalist Movement.” Feminist Review 44 (1993): 81-96. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1395197.

Saanika Patnaik is a recently graduated Master’s History student, currently pondering the next step in her life. A person guided by creativity and imagination, with a passionate interest in reading and writing, travelling and exploring. Strongly driven by the philosophies of feminism, individualism, and social equality. She can be found on LinkedIn and Facebook.

Featured image source: Kractivist

My suggestion to the author is to converse and interact with Prof. Dr.Ishita Banerji-Dhube who has an interesting article and lots of research on the evolution of Bharatmata iconography and may be to a certain extent even Prof.Dr.Jyotinder Jain the art historian.