Two thousand five hundred years ago, Buddhism created a revolution in India that is recognised in religious history as one of humankind’s greatest revolutions. When Buddha started Sangha, the Buddhists predominantly consisted of men. Women did not participate in the early beginnings of Sangha, therefore, many women wanted to join the Sangha and yearned for equality. However, they could not get easy access as there was no tradition of assimilation.

The Buddhist community comprised monks and nuns known as the Bhikkus and the Bhikunnis, respectively and the Upasakas and the Upasikas known as the laymen and laywomen, respectively.

In the Indian context, the need to closely examine ancient and modern political thinkers’ views on women’s question is greater because the Brahminical system had widened the gap between men and women by institutionalising practices like Sati widowhood, child marriage etc. Not surprisingly, these practices are as ancient as Buddha, Kautilya, and Manu. Hence, there is a greater need to examine Buddha’s political views on women in comparison with ancient Hindu thinkers.

Background

By the time Buddha began to discourse on his ideology and establish the Sangha, Indian women were passing through dark times. Kancha Ilaiah in his book God as a political philosopher writes, “The Indus valley culture of equality had been reduced to oblivion, and its urban luxuries disappeared. After this, the Rig Vedic Brahmanical society was established in which women lost all their social and political rights. Women’s position deteriorated through the ages of the Upa-vedas and the Upanishads. During this period, polygamy seems to have become the common practice, and the patriarchal structures of family and society overthrew all their socio-political rights.“

Also read: Understanding Buddhism Through A Feminist Lens

However, most of the leading schools of Buddhism, which are thriving today, are fully egalitarian in doctrine. Many of the problems women in Buddhist countries face today have more to do with deeply rooted social values that Buddhist theorists did not originate, but Buddhists have usually complicated. In comparison with some other religions, Buddhism has had little to say about what social roles should be since such questions have not been seen as directly pertinent to religious commitment and efforts.

What effect, then, might Buddhism have had on the formation of attitudes toward women in predominantly Buddhist countries, and what has it contributed to the self-image of Buddhist women themselves, and perhaps of non-Buddhist women living in societies affected by Buddhist ideas and conduct? Hard evidence is scant, and suppositions can run rampant.

With all the limitations and conditions the Sangha imposed on women, their admission nevertheless liberated them from household drudgery. The women who were admitted seem to have felt relieved of the bonds of family and household life.

However, it surely must be true that images in Buddhist literature of women as fully enlightened beings, as quick-witted teachers, compassionate friends, self-sacrificing saints and courageous heroines have had a positive effect on the sensibilities of women and men who have heard or read the old scriptures, poems, and popular stories. Symbolisms, too, which identify perfect wisdom as feminine, and the enormous popularity of female Bodhisattvas and goddesses in the Buddhist pantheons of Tibet and East Asia, have probably bolstered women’s self-respect. These things have certainly helped make both men and women immediately aware of the feminine’s dignity and power.

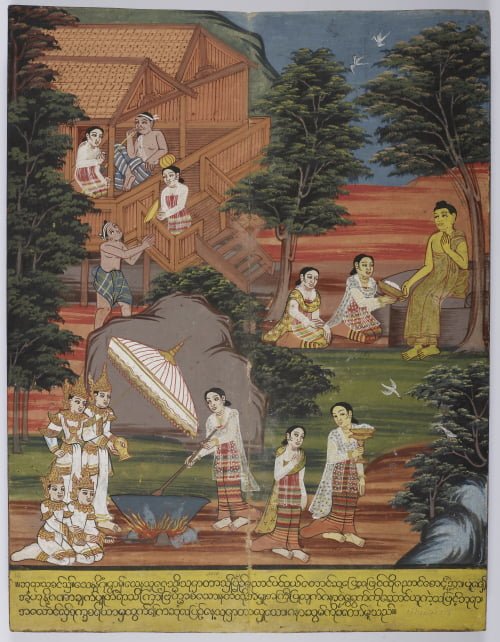

Admission to Women in Sangha

Perhaps the most crucial decisions that Buddha had to take in his lifetime concerned the question of admitting women into the Sangha. Like any other individual, he learned and evolved his understanding of issues in his struggle with his mental makeup and the entrenched value system that conditioned his own thinking. This struggle came out very clearly in his debate with Ananda over the admission of women. Of all the ancient sources, Buddhist literature alone does not hide that women themselves took the initiative to join the Sangha. The Sangha system responded to the demands of contemporary women positively.

Also read: Dalits & Religious Conversion: Tracing The History Of The Neo-Buddhist Movement

Maha Prajapati put forth her demand for admission in Sangha. Had it not been for the general counter-culture that Buddhism was creating against Brahmanism, such a demand by women to be permitted to renounce, the home would have been impossible. Hindu asceticism did not provide any scope for women to renounce household life. Buddha was, like everyone else, brought up in a patriarchal culture and could not immediately think of admitting women.

Maha Prajapati followed Buddha and went to Kapilavattu to Vesali; she cut off her hair and put on orange coloured robes. This time she never went alone, but with other women of the Sakya clan. In the initial days, Buddha was not willing to enter women in Sangha. Maha Prajapati put her request thrice and got the same reply from Buddha but did not lose hope. Then Maha Prajapati approached Ananda, who was more sympathetic to the rights of women than Buddha.

Buddha agreed on the condition that she should accept the eight rules. He made these eight rules very rigid, hoping that Maha Prajapati would refuse to join these conditions. They were:

- A Bhikkhuni, however senior she may be by age and experience, should always salute a Bhikkhu;

- A Bhikkhuni should not spend the rainy season in a district in which there is no Bhikkhu;

- Every half month, the Bhikkhunis should take a lesson from a male Bhikkhu;

- After the rainy season is over, every Bhikkhuni has to confess to a joint meeting of Bhikkhunis and Bhikkhus what has been seen, what has been heard, and what has been suspected;

- A Bhikkhuni who is guilty of a severe offence shall be punished in a joint meeting;

- A Bhikkhuni has to go through two years’ probation and will get full membership only when a joint meeting approves it;

- Under no circumstances should a Bhikkhuni revile or abuse a Bhikkhu;

- Officially, no Bhikkhuni shall be granted the right to admonish a Bhikkhu, but a Bhikkhu can admonish a Bhikkhuni.

As per Buddha, these standards ought to be respected and watched throughout the Bhikkhunis lives, and they were never to be violated. Mahaprajapati accepted them at once.

Also read: Therigatha: The First Writings Of Our Ancestresses

Buddha’s personal ambiguity should be understood in the context of his times. By admitting women into the Sangha, he was taking a revolutionary step. Society by then was looking at women as forces of disturbance; Hindu thought, and practice portrayed them only as pleasure-seeking beings. The socio-political values around them also influenced most of the Bhikkhus who joined the Sangha. Above all, his own upbringing and the patriarchal culture he inhabited conditioned him. With all the limitations and conditions the Sangha imposed on women, their admission nevertheless liberated them from household drudgery. The women who were admitted seem to have felt relieved of the bonds of family and household life.

How Did Bhikuni Sangha Start

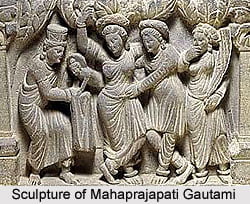

The Bhikuni Sangha started in a particular historical setting which was not very easy. We know a historical character named Prajapati Gautami, who was the aunt of Buddha, and she requested the Buddha to start the order of nuns. She led the group of 500 Sakya women, and they wore robes and shaved their heads and workers accepted into the Sangha. Thus was born the order of nuns in the Buddhist religion.

This was a historical element in this because spiritualism and renunciation was a vital avenue that was open to women and needed not necessarily be tied with the household. This was a legal, cultural and morally accepted way for women to enter Sangha, which marked a historical beginning. From this, Sangha expanded as patronage to Buddhism increased. With the rise in patronage towards Buddhism, we have the flowering of many Buddhist monasteries, but then at the same time, we do not have an equal number of the rise in Bhikkhunis and nunneries, which was the institutional setting for the Bhikunnies.

In Therigatha, Bhikkhuni Sumangala makes it clear that though she lives under a tree, she feels freed from drudgery and form the brutal husband who respected her less than the shade of a tree. This shows after joining a Sangha, women were free from all such bondage.

Therigātha is the story of elder nuns known as Theories, as we have Thera’s for elder monks. The Theri-gatha contains numerous stanzas that clearly express the feelings of joy experienced by saintly bhikkhunis at their ability to enter the order and realise the Truth. Furthermore, the Therigātha (The Songs of the Women Elders) of the Pāli Canon provides significant evidence recounting the struggles and triumphs of the first group of nuns who came from the highest rungs to the lowest in society. In some of the songs of Therigātha, we can understand how women felt after joining a sangha.

Also read: Shantabai Dhanaji Dani: The Dalit Woman Leader Who Fought Against Caste

For example, Sumangala, Bhikkhuni says:

“O Woman well set free! How free I am,

How wonderful free from kitchen drudgery,

Free from empty harsh grip of hunger,

And from empty cooking pots,

Free too of that unscrupulous man,

The weaver of sunshades.

Calm now and serene I am,

All lust and hatred purged.

To the shades of the spreading trees, I go

And contemplate my happiness.”

Sumangala makes it clear that though she lives under a tree, she feels freed from drudgery and form the brutal husband who respected her less than the shade of a tree. This shows after joining a Sangha, women were free from all such bondage.

Also read part two of this article: Women’s Participation In Buddhism

References:

- Ambedkar, Writing and speeches vol. P. 281.

- Buddha and his Dhamma, Dr. B. R. Ambedkar,

- Halkias, GT 2013, ‘The Enlightened sovereign. Buddhism and kingship in India and Tibet’, in

- Ilaiah Kancha, “God as Political philosopher- Buddha’s challenge to Brahminism”, Sage Publication 2019.

- P. Thomas, Indian Women through the ages: A historical survey of the position of women and the institution of marriage and family in India from remote antiquity to the present, Asia Publishing House, Mumbai, 1964.

- SM Emmanuel (ed.), a companion to Buddhist philosophy, John Wiley & Sons. Inc. Oxford.

- Therigatha, Pali Text Society, London, 1971.

- The Epistemological bases of Ambedkar’s Navayana, Forward press, 2017

Ashwini has a Master’s degree in Dalit and Tribal Studies and Action from Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai. She also holds a Master’s degree in Political Science from Savitribai Phule Pune University. She like to be involved in field based studies and providing sustainable solutions for upliftment of the society.

Featured Image Source: Encyclopedia of Buddhism

Buddham Sharanam Gachchhami?☸

Kancha Illyaha is intellectual lazy read Chinese and Arab primary sources and takes on vedic India. It’s not as regressive as it seems.