Read part one of this article: Women In Buddhist Sangha

With all his limitations and personal ambivalences about women, Buddha can be credited with five significant achievements:

- He recognised the political right of women to join the sangha;

- He forced the sangha to recognise women’s right to be leaders;

- Against the dominant Hindu view Buddha held that a woman can develop her own personality and individuality independent of any male support;

- He broke the myth of family and the importance of producing male children to attain salvation; and

- He was the first to recognise the need for women’s education and political initiative.

Let’s take a look at these five innovations one by one, studying how Buddha and his sangha handled these issues and in the process analyse the strength and weakness of Buddha’s understanding.

Though relatively speaking the number of women who joined Buddhist sanghas was small, the fact that the writings of 73 women were included in the Gatha records, shows that the bhikkhunis inspired vast sections of women.

To join the Sangha, a women should have reached 20 years of age, be free from debts, not be in the king’s service; should obtain the permission of her parents if living, be duly provided with robes and alms bowl and recommended by an ordained bhikkhuni. Several women contemporaries of Buddha seem to have treated the establishment of the sangha as a new opportunity. Both within the family and outside, women were granted no personality and individuality of their own; with the establishment of the sangha and the admission of women into them, there was now an opportunity for women to improve their status. Though relatively speaking the number of women who joined these sanghas was small, the fact that the writings of 73 women were included in the Gatha records, shows that the bhikkhunis inspired vast sections of women.

After joining Sangha, women found dignity and respect like Sumangala, Mathika, Vasanti, Sumedha, Utpalavarna. Several sex workers who were looked down upon by society joined the sangha and acquired a respectable place. Arthakasi of Kasi, Padmavati of Ujjain and Ambapali (Amrapali) of Vesali were noted women who came from this background and enjoyed a high reputation.

Buddha declared that women could attain nirvana. While the Hindu thinkers denied the right to education to women of all castes and classes, the Buddhist sangha gave them the freedom to read and write. Thus, the first generation of women intellectuals in India emerged from the Buddha sangha. For example, Ambapali, Sumangala, Mathika, Ishidasi, Subha and many other women not only acquired the skills of composing songs but assumed enormous importance in sangha life. The bhikkhuni sangha encountered enormous problems because of the unequal treatment meted out to women.

The sangha system itself was operating under the enormous influence of gender distinctions. For example, while the bhikkhunis when compared with Hindu women were far closer to being free citizens and were liberated souls, within the sangha the bhikkhus had superior status. This only indicates that achieving women’s equality requires the bitterest battle, a far more protracted one than that required to establish the equality of castes and classes. This is because any class of men treat women of their own class as subordinates and as objects of oppression and so do men of all castes. Buddha’s sangha also operated within that patriarchal paradigm.

Gender and Salvation

Despite women’s space in these religions, Indian patriarchal norms prevailed here as well. The founder was male sage, hence monks became the paradigm, and nuns the ‘Other’. Moreover, as most theologies were male constructions, women’s subordination became scripturally ordinated.

Learned women (archaryis) instructed other nuns, but even male novices rarely accepted women teachers. Sangha hierarchies clearly mirrored lay patriarchal norms. One scholar conjectures that female subordination led to the decline of Buddhist nuns’ orders in India. Despite entrenched patriarchy, early Hindu and Buddhists did not question women’s right to salvation. The Hindu belief in virtue and Dharma, powerful goddesses, and a neuter Brahman show that gender is a trivial distinction on the path to moksha. Buddhists believe that Nirvana is available to all virtuous individuals, irrespective of social conditions.

Buddhism and women: The Dhamma has no gender

Buddhism emerged as a pragmatic school and influenced the people. It became a mass movement because quite successfully it mediated between spiritualism, materialism and also collectivism. Buddhism does not consider women as being inferior to men. Buddhism, while accepting the biological and physical differences between the two sexes, does consider men and women to be equally useful for the society.

In Buddhism, both husband and wife are expected to share equal responsibility and discharge their duties with equal dedication. The husband is admonished to consider the wife a friend, a companion, a partner.

The Buddha emphasises the fruitful role a woman can play and should play as a wife, a good mother in making the family life a success. In the family both husband and wife are expected to share equal responsibility and discharge their duties with equal dedication. The husband is admonished to consider the wife a friend, a companion, a partner. In family affairs the wife was expected to be a substitute for the husband when the husband happened to be indisposed. In fact, a wife was expected even to acquaint herself with the trade, business or industries in which the husband engaged, so that she would be in a position to manage his affairs in his absence. This shows that in the Buddhist society the wife occupied an equal position with the husband.

Also read: Understanding Buddhism Through A Feminist Lens

Buddhism does not restrict either the educational opportunities of women or their religious freedom. The Buddha unhesitatingly accepted that women are capable of realising the Truth, just as men are. This is why he permitted the admission of women into the Order, though he was not in favour of it at the beginning because he thought their admission would create problems in the Śāsana (a term frequently used by Buddhists and Shaivites to refer to their religion or non-religion. It has a range of possible translations, including teaching, practice, doctrine, and Buddha Śãsana, which means “the teaching of the Buddha”). Once women proved their capability of managing their affairs in the Order, the Buddha recognised their abilities and talents, and gave them responsible positions in the Bhikkhuni Sangha. The Buddhist texts record of eminent saintly Bhikkhunis, who were very learned and who were experts in preaching the Dhamma. Dhammadinna was one such Bhikkhuni, Khema and Uppalavanna are two others.

Buddhism’s greatest contribution to the social and political landscape of ancient India is the radical assumption that all men and women, regardless of their caste, origins, or status, have equal spiritual worth. This is especially pertinent concerning the status of women, who were traditionally prevented by the brāhmanas from performing religious rites and studying the sacred texts of the Vedas. Halkias (2013, p. 494)

Navayana perspective

Dr. Ambedkar interpreted and contextualised the framework of Budhha-Dhamma-Sangha as Navayana, the ‘New Way’ and freed Buddhism from the Brahmanical clutches. It was meant to be the vehicle for emancipation of humanity. Ambedkar realised that if Buddhism continued to be an intimidating and highly institutionalised order of renunciants, priests and intellectuals, it would never be able to absorb India’s Dalits. That paved the way for Navayana. Navayana means a new vehicle riding towards equanimity, a new vehicle of the emancipation of downtrodden people, it is a new vehicle of freedom of mind, aesthetics of life. Navayana is the wheel of life which continuously rotates and moves forward for the development of an individual as well as the society.

Ambedkar’s Navayana is a reformed form of Buddhism where men and women are equal at every and each field of social and religious life.

Dr. Ambedkar historically conceptualised the dominance of Brahmanism towards downtrodden indigenous people. He found that Brahmanism will not allow the development of Dalits or other backward castes. So strategically he searched for Dalits of the other religion. He studied all the religions of India where he found Buddhism to be the most grounded scientific and destroyer of Brahmanism.

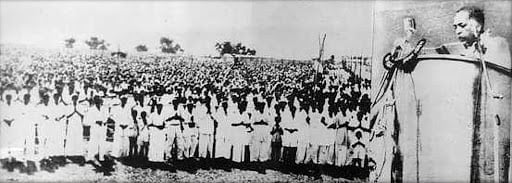

In 1935 he announced that though he was born Hindu, he will not die as a Hindu. This was the first sign of conversion. On 14th October 1956, Dr. Ambedkar led mass conversion of thousands of people in Nagpur. He gave Buddhism to India in a much filtered form as before him, Buddhism was dominated by brahmanical practices. Ambedkar’s Navayana is a reformed form of Buddhism where men and women are equal at every and each field of social and religious life. Ambdekar’s Navayana Buddhism has not changed the core of buddhist principles but only changed the reasons for applying it in newer changed modern social settings.

Also read: Dalits & Religious Conversion: Tracing The History Of The Neo-Buddhist Movement

References

- Kancha Ilaiah, “God as Political philosopher- Buddha’s challenge to Brahminism”, Sage Publication 2019.

- Therigatha, Pali Text Society, London, 1971.

- Kancha Ilaiah, “God as Political philosopher- Buddha’s challenge to Brahminism”, Sage Publication 2019.

- Ambedkar, Writing and speeches vol. P. 281.

Ashwini has a Master’s degree in Dalit and Tribal Studies and Action from Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai. She also holds a Master’s degree in Political Science from Savitribai Phule Pune University. She like to be involved in field based studies and providing sustainable solutions for upliftment of the society.

Featured Image Source: a mural from Wat Pho in Bangkok

Jainism also encouraged females. Founder of Ayodhya Nagari, Teerthankar Bhagwan Aadinath gave Deeksha to both his daughters, Brahmi and Sundari.

There are hundreds of examples in Sanatan also. But not as of in Jain and Sanatan, Buddha Bhikshus contained mix of She’s and He’s, and get DESTROYED.

One sided praise without studying other. Crap.

nice post

NHAI Recruitment 2021 Apply Online For NHAI Deputy Manager