As the Marxist critic Louis Althuzer put it, social institutions like the school function as part of the ideological state apparatus. In the earliest days of English colonial education being imported to India, much of the curriculum was structured in tandem with the aims of missionary activities.

When the Swadeshi and Nationalist movements gained momentum, the boycott of colonial education was supplemented by the promotion of alternative, indigenous systems of learning. The English system of education was later inherited by the modern Indian nation state, and the overarching influence of dominant state ideologies continued to be discernible within the curricula.

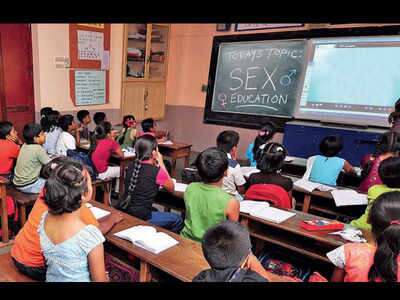

Thus, the puritanical attitude towards sex and sexuality characterising the mainstream Indian social order, also finds expression within the school environment. The most remarkable example of the same can be found in convent schools across the country. A colonial British import, convent schools run by missionary organisations have come to occupy an important space within the sphere of education in India.

Hailed by Indian guardians for their emphasis on discipline and decorum, most convent institutions have strict rules regulating students’ demeanor, appearance, and even communication.

The importance accorded to moral character in our schools also results in frequent moralising, with comments on the length of students’ skirts or their posture in class. Delving into any kind of gender sensitisation or sexuality education was never on the cards. A former student of Carmel Convent School shared how “sex” was viewed as a bad word during their initial teenage years, and conversations around feelings like “physical attraction” were taboo.

However, the prudish approach to questions of gender identity or sexuality isn’t characteristic of any one kind of school alone. As a student of Ashok Hall mentioned, teachers in her school would disapprove of girls hugging each other or displaying any kind of intimacy. Conversations about gender were restricted to gender studies or human rights classes, which didn’t start until class 11.

Contrarily, most ISC schools in our city of Calcutta did not even offer the options of such subjects, thus, closing off the possibility of discussions even in an academic context. Interestingly, prudishness towards sexuality was largely a colonial, Victorian cultural import, not unlike missionary education itself.

For instance, section 377 of the Indian Penal Code was a relic of the British Raj, which remained a topic of contestation till it was scrapped by the Supreme Court in 2018. Regardless of whether we are to attribute these notions to our colonial legacy, or view them as being more intrinsic to Indian moral history, our contemporary lived reality necessitates structural changes in this kind of thinking.

Halfway through middle school, most us knew what same-sex attraction existed, but we would still often laugh or speculate about relationships between those friends who seemed “too close ”

Even with the historic 2018 SC ruling, social realities in India haven’t changed significantly. As Aparna Narrain wrote for The Hindu back in 2019, we still need more conversations about queer identity and non-normative sexualities. A change in legislation alone can do very little to bring about sensitisation at the grassroot levels, which renders educational institutions one of the most important sites of effecting systemic change.

I remember the sense of curiosity and wonder that most of my peers and I felt around some of our seniors who didn’t fit into the conventional moulds of femininity – those who wore their hair cropped short, walked with a slightly different gait, and always stuck to plain t-shirts and jeans on occasions that allowed for casual clothes to be worn.

Also read: Un-Tabooing Children’s Sexuality: A Need Of The Hour

For students from all-boys schools like Don Bosco, this sense of wonder would often be replaced by ridicule, if the situation were to be reversed with a male student coming across as feminine. Halfway through middle school, most us knew what same-sex attraction existed, but we would still often laugh or speculate about relationships between those friends who seemed “too close.”

The enigma of our tomboyish seniors reached such proportions, that juniors often expressed their adoration for them, even with cards and letters! And yet, never through all of these experiences did a single teacher ever attempt a conversation that could disentangle some of the confusion we felt, navigating our way through adolescence.

A 2019 incident of a 19-year-old school-going boy’s death by suicide after being bullied for his sexuality, sparked off conversations about the need to make our schools safe spaces. While grappling with questions about one’s own sexuality and gender identity through the changes of adolescence can alone be daunting, lack of support from one’s home and peers, or hostility in the form of bullying and shaming takes a pronounced mental health toll.

We’ve traversed past Queer Pride month but our acknowledgment and celebration of pride cannot be reduced to a recurring phenomenon, one month a year. Sensitisation and collective action need to be ongoing and stemming from the grassroot levels. Thus, when it comes to sensitising a younger generation of individuals to the nuances of gender identity and sexuality, and the significance of free love, we need to hold our schools and education policy-makers accountable

An independent survey conducted with respondents mostly from Calcutta, who’ve attended English medium schools, revealed that 92% of them attended schools which offered no sexuality education, and 89.5% of them witnessed students being bullied and chastised by both peers and teachers for their gender expression. 89% of them stated that their faculty members never tried to untangle these notions for them, and opined that a more sensitised and inclusive school environment would have helped them understand things better.

Even though Indian state governments had agreed to include sexuality education within their curricula in compliance with commitments to the 1994 United Nations International Conference on Population and Development, private schools have had the option of not implementing similar programs.

Even the MHRD’s Adolescent Education Program was not introduced in many schools, and got banned in 12 states. Former Teach for India fellow and educator, Riju Banerjee wrote about the need for teachers to be sensitive and empathetic to differences within the classroom. Identifying as queer herself, Riju brought a different kind of subjectivity to her teaching experience, which isn’t true of all teachers we may have grown up with. However, the need to unlearn biases and inculcate empathy is a necessity for all educators across the board.

Regulating the private sphere of the home, to help queer individuals who struggle to come out to their families or are ostracised and even punished for doing so, is not entirely feasible. The idea of the home as a safe space is itself a myth, as has been revealed in multiple cases, like the death by suicide of a 21 year old student from Kerala who had been forced into conversion therapy by her family

Emphasising on the need for the same during a conversation, Modern High School Director Devi Kar said, “We should think of education as a holistic, rounded concept.” Over time, the MHS administration has introduced a number of programs beyond the prescribed curriculum, to focus on skills development and sensitisation, including sexuality education and relationship counselling. The programs are conducted by trained professionals appointed by the school administration.

We have also started off with something that has been appreciated, and we call it the peer support group, with our senior students having virtual rooms to meet, where people are allowed to come in anonymously to discuss things,” she added.

This is a format that has been functioning throughout the lockdown and pandemic, and Mrs. Kar reiterated the need for such initiatives to be ongoing regardless of external circumstances. Of our survey respondents, a few students of Kendriya Vidyalayas mentioned that their schools had similar programs, and their responses indicated a change in their understanding of gender and sexuality than for those who received no such education in school.

Regulating the private sphere of the home, to help queer individuals who struggle to come out to their families or are ostracised and even punished for doing so, is not entirely feasible. The idea of the home as a safe space is itself a myth, as has been revealed in multiple cases, like the death by suicide of a 21 year old student from Kerala who had been forced into conversion therapy by her family.

Herein, the school emerges as the most significant site of not just learning, but also refuge. Implementing policies that make sexuality education and sensitisation a part of school curricula, and training educators and counsellors to impart such education and offer support to students is an achievable reality. However, as Mrs. Kar says, this needs to be an ongoing process and not just a knee-jerk reaction to certain incidents that make it to the newspapers.

The need for government intervention becomes especially important, because not every school might have the means to implement such programs independently. A regulatory framework becomes essential in ensuring that such a model doesn’t end up excluding students who can’t afford the privilege of a private education.

However, even in this context, organisations like Teach for India, (TFI) which work on education and capacity building with first or second generation learners from low income backgrounds, are setting an example. Collaborating with Calcutta-based gender justice advocacy group Rangeen Khidki Foundation, TFI is training their 2021 cohort of fellows to impart sexuality education to the students they will be teaching. “The organisation has consistently encouraged their fellows to engage with their students on these matters,” said former fellow Shinjinee Pal, who herself had conducted sessions along with the Aks Foundation during her fellowship.

We’ve traversed past Queer Pride month but our acknowledgment and celebration of pride cannot be reduced to a recurring phenomenon, one month a year. Sensitisation and collective action need to be ongoing and stemming from the grassroot levels. Thus, when it comes to sensitising a younger generation of individuals to the nuances of gender identity and sexuality, and the significance of free love, we need to hold our schools and education policy-makers accountable.

Also read: Challenging The Status Quo Of Sex Education in India

Puja Basu is a recent English literature postgraduate from Jadavpur University, with a keen interest in the intersection of media, gender, and cultural studies. You can find her on Instagram and Twitter.