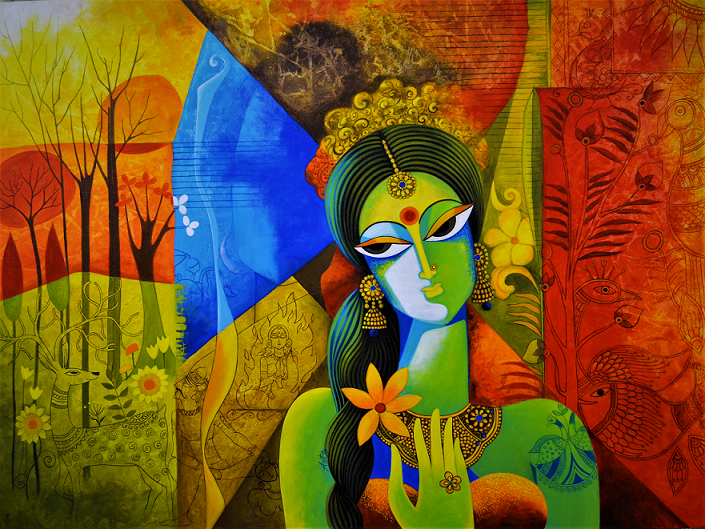

As a young feminist still struggling every day to define and determine my religious beliefs, I have always wondered whether Hinduism, essentially, is feminist? A lot of these stories also played an instrumental role in my Hindi lessons, understanding of Hindu mythology and customs as well as my learning of Indian classical dance and music.

Growing up, I was always told about the two epics—the Ramayana and Mahabharata—and they grew to become a pivotal part of my upbringing and spiritual exposure, especially considering the fact that 8-year-old me watched a cartoon adaptation of the Ramayana and was horrified at the way Sita was objectified and treated like a prize. It also caught me off guard while trying to understand Shoorpanaka’s rather complex character arc as well as her story.

The stories I was familiarised with from a young age still continue to play a role in my life, particularly in the way I view the world. I have internalised some of those early learnings from my childhood and adolescent years. A lot of the problematic notions about being ‘Sanskari’ are invariably rooted in these myths and epics.

Sadly, a lot of these stories weren’t written for the young girls today who aspire to be so much more and need strong female ‘role models’ to look up. We sometimes have to do a little soul searching and understand these stories in different ways so that we see that small glimmer of hope that may resonate with us too.

Gandhari, Kunti and Draupadi

Most of the female characters in our epics have very little choice when it comes to consent, marriage and freedom of expression. For instance, one may see that Draupadi in the Mahabharata may have been the closest to what one would call a ‘feminist icon’ by any stretch. She is a character who was dishonoured and humiliated at the Rajsabha. Even though she remains an important part of the story, she is relegated to a fringe and is often used as a scapegoat in most of the decisiove moments of the narrative.

She remains an afterthought and is silent in the course of the Kurukshetra war. Though the war is deemed to have begun to redeem her, she essentially has no say in what course it must take. Many of the female characters in the Mahabharata, unfortunately, also serve as a tool to embolden problematic, partisan ideas and beliefs.

We can see that the female characters in the epics invariably become reduced to gender roles, despite being fierce and capable in their own right. They are considered as extensions of male characters and have very little say in pivotal events in the storyline. Their strength often comes through with their ability to sacrifice or nurture. Though these qualities are of course positive, in the absence of complete agency, they seem to not serve much of a purpose in fully realising the potential of these women

The hierarchical relationships in the Mahabharata are often determined on the basis of gender as well as seniority and age at the same time. There is a certain amount of respect that is paid to elderly women such as Gandhari, especially when Duryodhan goes to seek her blessings before the upcoming war, knowing fully that she was vehemently against the war.

The five Pandavas also married Draupadi because their mother Kunti had wished upon them to do so and they wanted to honour her. However, the moment Draupadi becomes a part of the family, she succumbs to the traditional gender roles customary for a ‘good wife’ who would always be there to serve her partner and family.

Also read: Untheorised Heroines: Aristotle, The Ramayana And Indian Women

What struck me most was also the ‘undressing of Draupadi’ especially when I think about the reception the story may have today. It is all the more appalling when one thinks about the fact that these stories were carried on from generation to generation and have left their impact on young women. The way in which Duryodhan chose to seek ‘revenge’ on Draupadi and the Pandavas, and the approval this act received from the elders in the sabha speaks volumes about how a wife is considered as the property of the husband, and thereby, a tool to humiliate him.

Duryodhan believed that stripping a warrior off his weapons was equivalent to stripping ‘his‘ woman off her clothes and besmirching her honour. The idea that a woman’s honour lies in her body/nudity is also yet another concept that confirms to the patriarchal bias towards the belief that women are afterall, their bodies.

We can see that the female characters in the epics invariably become reduced to gender roles, despite being fierce and capable in their own right. They are considered as extensions of male characters and have very little say in pivotal events in the storyline. Their strength often comes through with their ability to sacrifice or nurture. Though these qualities are of course positive, in the absence of complete agency, they seem to not serve much of a purpose in fully realising the potential of these women.

Feminist readings of the epics

There has been a lot of research and considerable insight has been developed into more feminist interpretations of the Indian epics and how they play a role in today’s discourse. Feminist revisionist mythology is an area that aims to further this conversation. Today, we are even beginning to retell the Mahabharata and other epics through the feminist lens, and addressing many sexist ideas that remain entrenched in their storylines, so that we can engage with them without discrediting their richness of content.

Looking back, we may be uncomfortable to learn about some of the lessons and messages that these myths and epics seek to impart to us. Yet, at the same time, retelling them and understanding the gaps not only allows us to look at them from a progressive perspective and as a product of a context, but also as a way in which we can preserve their foundations

Anushkaa Hardikar in her e-magazine puts the task to the test by creating a scenario where Draupadi, Kunti and Gandhari sit down to speak about some of the struggles they face, particularly, shaming, ‘virginity,’ body image as well as marriage. She believes that this ‘radical and updated version’ of the Mahabharata can set a great example for us today, especially in the way in which we look at the ‘Nari’ or female.

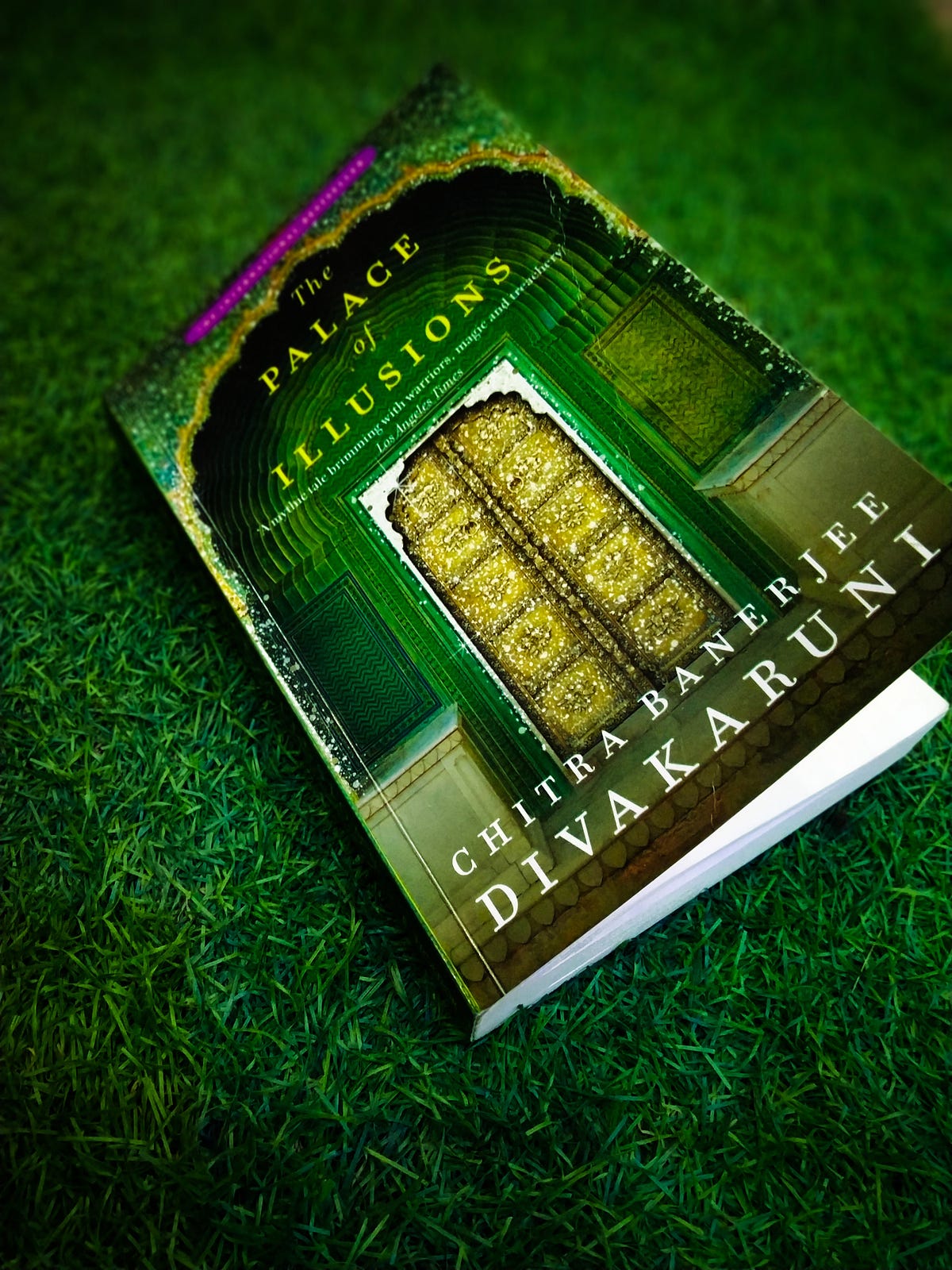

Moreover, books such as Karna’s Wife, The Palace of Illusions, Forest of Enchantments, Yajnaseni, and the like explore the individual lives of some of the pivotal female characters from the epics. They offer realistic and authentic portrayals of characters like Draupadi, Sita and Urvi. Winds of Hastinapur is also another equally powerful retelling of the Mahabharata that helps challenge the social outlook it has had on society so far.

Looking back, we may be uncomfortable to learn about some of the lessons and messages that these myths and epics seek to impart to us. Yet, at the same time, retelling them and understanding the gaps not only allows us to look at them from a progressive perspective and as a product of a context, but also as a way in which we can preserve their foundations.

Also read: A Feminist Reading Of Supporting Female Characters From Indian Epics

Featured Image Source: Bonobology

About the author(s)

Shivani is currently a political science undergraduate student enrolled at Sciences Po Paris. She hopes to embark on a career in investigative reporting and journalism. Shivani is a lover of coffee, obscure films, sitcoms, political podcasts, and siestas. In her free time, she enjoys writing and curating her next Spotify playlist.