The Human Rights Watch (HRW) report on India is a balanced overview, entailing the judicial, political and governmental actions that protected or stripped away civic rights, in 2022. Notably, authority-inflicted or complicit discrimination has been rampant—with arbitrary violence, imprisonment, and allegations wreaking devastation upon marginalised communities, rights-focused organisations, journalists and activists. At the same time, some SC rulings and foreign policy strategies have been deemed progressive.

Hidme Markam, an Adivasi anti-mining activist, who had been arrested for nearly two years, was finally released (on bail) this month. She was arrested during a Working Women’s Day event that aimed to protest against the custodial torture and sexual violence of Adivasi women. Like her, thousands of Adivasis have been criminalised and arbitrarily detained for years together.

Given the several reports last year, including those by the Early Warning Project, Freedom House Report, the V-Dem Institute, and the US Commission on International Religious Freedom, amongst others, have suggested that India’s policy has been “deeply alarming”, this report too observes a rightfully critical tone when analysing recent events.

“Freedom of Expression” permitted; Journalistic criticism not

Over the course of the year, free speech (particularly against the government, or its upheld Hindutva, Brahmanical and patriarchal politics) has been increasingly compromised through imprisonment and restriction—often under vague charges and draconian laws.

HRW’s Acting Executive Director Tirana Hassan condemned the Indian government’s oppressive actions: “…Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Hindu-nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party has mimicked many of the same abuses that have enabled Chinese state repression—systematic discrimination against religious minorities, stifling of peaceful dissent, and use of technology to suppress free expression—to tighten its grip on power.”

Recurrently, authorities have attempted to silence those who have been critical of governmental action.

Last year’s World Press Freedom Index for India echoes the same diminishing autonomy of independent journalism, in a country with “violence against journalists”, “politically partisan media” and “concentration of media ownership—factors which Reporters Without Borders cited for its poor ranking of 150/180. This is in spite of India signing the G7 call for “guarding the freedom, independence and diversity of civil society actors” and “protecting the freedom of expression and opinion online and offline”.

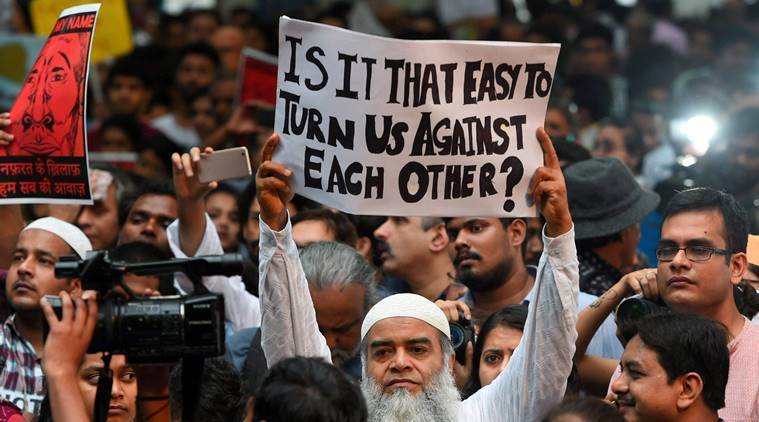

Muslim female students’ autonomy to wear a hijab to educational institutions in Karnataka was denied by the state high court—the Supreme Court failed to deliver their verdict on the matter. Earlier in the year, the personal information of several Muslim female activists, journalists and public figures was displayed online under derogatory, traumatic and inhumane conditions. The year has also borne witness to several cases of violation of the right to secure housing, with the government enacting illegal demolitions—stripping down the homes of Muslim people in Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat, and Delhi.

In February, last year, two UN special rapporteurs expressed their concerns on the unchecked harassment being faced by an independent journalist and human rights defender Rana Ayyub in light of her critical reportage on the mishandling of the pandemic and state-abetted discrimination of marginalised communities.

HRW also notes about the political sensitivity and particular suppression of media, movement and basic rights in Jammu and Kashmir, in the 3 years after the scrapping of Article 370. Many journalists from the region, including pulitzer-winning photojournalist Sanna Irshad Mattoo, have faced increasing barriers when trying to report independently.

Unjust carceral discrimination for activists

Following the undemocratic ideal of preserving freedom for those who’re not critics of the government or majoritarian privilege—i.e. politicians who can get away with publicly disseminating hate speech, inciting violence, and celebrating crimes against humanity—several humanitarian activists were put behind bars.

Also read: Early Warning Project Report Warns Of Hindutva Politics’ Mass Killing Risks

The Human Rights activist Teesta Setalvad, who has been seeking justice for the victims of the Gujarat 2002 riots and working for the prosecution of the authorities in power at the time, was arrested in June. Meenakshi Ganguly, HRW’s South Asia director spoke out on this matter: “No one can deny that the violence occurred, or that there needs to be justice, and yet the authorities have been pursuing criminal charges against Teesta Setalvad for years now in an attempt to silence her.”

Hidme Markam, an Adivasi anti-mining activist, who had been arrested for nearly two years, was finally released (on bail) this month. She was arrested during a Working Women’s Day event that aimed to protest against the custodial torture and sexual violence of Adivasi women. Like her, thousands of Adivasis have been criminalised and arbitrarily detained for years together.

“With the destructive effects of climate change intensifying around the world, there is a legal and moral imperative for government officials to regulate the industries whose business models are incompatible with protecting basic rights,” reads the general HRW’s World Report overview. In recent years, however, Indian decision-makers have failed to protect the environment, consequently endangering human rights. Policy-makers cannot continue to be complacent in corporate destruction of ecologies and climate injustices.

This comes when, in August last year, the National Crime Records Bureau reported a rise in crime against Dalit, Adivasi and Religious Minority Communities. The National Human Rights Commission also registered 147 deaths in police custody, 1882 deaths in judicial custody, and 119 alleged extrajudicial deaths. This impunity of public safety forces has resulted to severe violations of the rights of, often innocent, civilians.

Civil society and rights violations

The offices of several prominent non-governmental human rights organisations—including Oxfam India, Centre for Promotion of Social Concerns, and Public Spirited Media Foundation—were raided on allegations of financial frauds.

Muslim female students’ autonomy to wear a hijab to educational institutions in Karnataka was denied by the state high court—the Supreme Court failed to deliver their verdict on the matter. Earlier in the year, the personal information of several Muslim female activists, journalists and public figures was displayed online under derogatory, traumatic and inhumane conditions. The year has also borne witness to several cases of violation of the right to secure housing, with the government enacting illegal demolitions—stripping down the homes of Muslim people in Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat, and Delhi.

Also read: Women Journalists: Reporting Loss From The Global South

This discrimination against those from religious minorities has worsened in 2022. Open Doors (UK), an advocacy NGO on the rights of Christians internationally, in their World Watch Report of January 2022 ranked India as 10th in the list of countries where Christians faced the worst persecution levels. The year had several instances of violence against Christian communities, with Christians from Dalit and Adivasi Communities being arbitrarily arrested on forced conversion charges in Uttar Pradesh.

In March, a Rohingya Muslim refugee was forcibly deported back to Myanmar (where she would face grave risk), separating her from her children and family—despite the Manipur State Human Rights Commission’s order otherwise. This was after already having not seen her family for a year, due to arbitrary detainment.

The 11 convicts of the gang rape and murder of Bilkis Bano and her family were released early by the BJP government, risking their personal and public safety. When she submitted a petition to the Supreme Court challenging this release approval, her appeal was dismissed.

Hopeful progressions

The Supreme Court did enact some progressive rulings. 2022 marked the year, when accessibility of legal abortion was increased to all those who might need one, regardless of marital status or whether or not they identify as cisgender women. In another crucial judgement, the SC broadened how “family” is constitutionally defined—enabling access to family benefits to include same-sex couples, single parents and households considered “atypical.”

A colonial-era law that government authorities have frequently wielded to crack down on free speech—the sedition law—was finally suspended by the Supreme Court in a historic August ruling. The pleas against its constitutional validity and for its scrapping down is yet to be heard in court.

Intersectionality and notes on 2023

However, while these judgements deserve their due celebration for the lives improved, people in positions of power mustn’t forget that an intersectional understanding of human rights is what we need. For one, the RSS chief’s all new “progressive” values on queer rights cannot be lauded.

A judicial improvement in one segment of human rights, while others are violated in the masses, renders the improvement marginal for those who’re also experiencing religious, caste-based, and/or ableist marginalisation.

Structural exclusion of certain identities means that the implementation stage of constitutional rights is unsuccessful, resulting in an ineffective final impact.

This failure on the part of the final implementing actors is notably observed in a continued inaccessibility within built environments and institutions–despite the 1995 and 2016 acts for People with Disabilities.

Cases of promised financial support for the education of students experiencing marginalisation being withdrawn or delayed also hinders progress for equitable rights.

A colonial-era law that government authorities have frequently wielded to crack down on free speech—the sedition law—was finally suspended by the Supreme Court in an August ruling. The pleas against its constitutional validity and for its scrapping down are yet to be heard in court. This could potentially improve the current state of the right to expression, tremendously.

Also read: What Universal Periodic Review Says About The Under-Reported GBV In India

“With the destructive effects of climate change intensifying around the world, there is a legal and moral imperative for government officials to regulate the industries whose business models are incompatible with protecting basic rights,” reads the general HRW’s World Report overview. In recent years, however, Indian decision-makers have failed to protect the environment, consequently endangering the rights of Adivasi/Indigenous communities, the rights of youth, and the rights of all living bodies whose fate rests in a future on Earth. Policy-makers cannot continue to be complacent in corporate destruction of ecologies and climate injustices.

On civil rights, in this speech during his visit to India, António Guterres called for the preservation of basic rights “by condemning hate speech unequivocally, by protecting the rights and freedoms of journalists, human rights activists, students and academics.”

Maybe India would do well to heed to the UN Secretary General’s words. “India’s voice on the global stage can only gain authority and credibility from a strong commitment to inclusivity and respect for human rights also at home.”