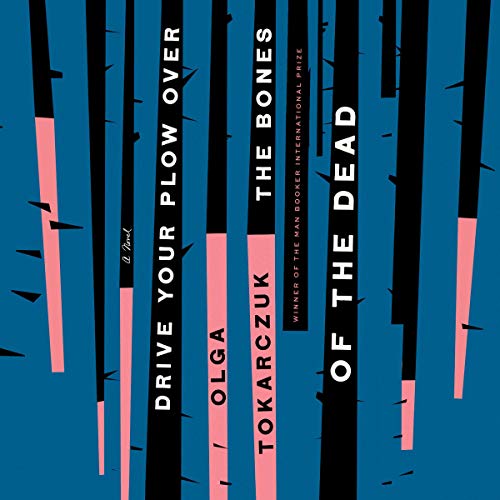

Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead, is a novel written by the Nobel Prize-winning Polish writer, Olga Tokarczuk. Set in Klodzko, a picturesque, albeit, hostile snow-laden valley of Poland, we are introduced to Janina, a teacher, who is among the three people who are brave enough to face the harsh winter that plagues their village.

Janina also tends to the houses of absentee owners who return to the village in the summer. When members of a local hunting party are found dead, she is convinced that they were punished by the very same animals they hunted; in this case, deer. Aspersions on her sanity, titters, and a condescending attitude; nothing deters Janina in her unwavering belief in divine justice.

When the ability to think makes you ‘eccentric‘

From the beginning of the novel Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of The Dead, the author establishes that Janina is not, or rather, chooses not be a ‘normal,’ woman. Janina observes life and its banal rituals with a comic detachment. She lives alone, pays no heed to what she wears, and shuns most human company while thriving in solitude. An extremely sensitive individual, her sensitivity is not limited to animals and plants, but to the very houses of the village, whom she considers as sentient beings. She is the classic ‘eccentric,’ the ‘crazy cat woman,’ minus the cats.

The attractive woman can serve men as an object of desire; Janina cannot. Janina is not a socially aesthetically pleasing woman; in addition to being old and grey haired, she gives a description of herself as someone who is of a large build, suffers from digestive problems, and has, on one occasion, ‘pissed red.’

On complaining to the local authorities about illegal poaching, she is asked why ‘old women,’ like her care so much about animals. Multiple times during the course of the Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of The Dead she is referred to as a ‘mad old lady,’ primarily by men in power; be it the police officials, civic bodies, or rich landlords.

When one ‘ceases to be a woman‘

The men in the novel, have ceased to consider her as a living, breathing, and thinking person. They are patronising towards her, often sharing knowing glances with each other, while she is present and trying to draw attention towards their lack of response towards their duties. The use of condescending humour is catalogued by Janina in a detached way, even as she wonders if more attention would be paid to her if she were a moustachioed young man or an attractive young woman.

The attractive woman can serve men as an object of desire; Janina cannot. Janina is not a socially aesthetically pleasing woman; in addition to being old and grey haired, she gives a description of herself as someone who is of a large build, suffers from digestive problems, and has, on one occasion, ‘pissed red.’

The only time when she is expected to participate socially is during the funeral prayers of ‘Big Foot’. Despite being labelled as ‘eccentric’, the reader is forced to wonder with Janina, why she has to be the one to lead prayers (the reply was that she was a woman).

When rational actions turn women into irrational being

The premise that the law is binding and rational, is an imperative part of an individual’s relation with others and with the state. Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of The Dead also sheds light on what the popular conception of madness is. The poaching, and most of the hunting being done is against the law. It is Janina who approaches the local law enforcement authorities to complain about poachers like ‘Big Foot.’ This ‘rational,’ and law-abiding action is viewed as madness, whereas the action of those violating the law is not.

Sensitive towards all living beings and most non-living things, she is mindful of the laws of nature. She buries the bones of poached animals in front of her house, but the carcasses she leaves behind where another animal, a predator, might find them and consume them.

Janina understands the brute force needed to survive, what she doesn’t understand and therefore does not forgive is a mindless hunger with no appetite. For food, for alcohol, for sex, for money, a hunger for the sake of hunger.

I don’t fit in, and neither do my friends

Janina’s complete disregard for masculine and heteronormative rules is evident in her close friendship with her student Dizzy; a ‘delicate,’ and ‘blushing,’ young man who translates William Blake’s poetry into Polish; good News, a bald young woman with ‘Manchurian,’ features; Doctor Ali; a middle-eastern expat, who, while a dermatologist, is empathetic towards and understands how Janina’s state of mind affects her body in the form of various ailments.

She refuses to accept the authority of the highest rung of society’s order; the young, cis-gendered, white man; bursting with testosterone, finding an outlet for his masculinity in pointless violent acts such as killing animals for entertainment, or domestically abusing their family. Janina would rather spend time with her friends or with a researcher, perched on the forest floor in is search for endangered bugs.

The ‘eccentric,’ Janina hosts the researcher in her house, clearly outlining that living independently not only stems from her need for solitude, but from her rejection of people who would constantly remind her that she was weird or wrong.

When romance is not paramount and sex is incidental

In one particularly poignant line, she chooses to not describe the physical part of a relationship, stating that she is “neither sentimental nor maudlin.” Her refusal to make romantic relationships the central theme of her narrative is another example of how she rejects societal expectations. Naturally, she is ‘crazy.’ She also forces the reader to question the concept of love and its socially approved recipient.

Can a ‘beloved,’ be only one’s lover? Can it not be a book, a pet, or a frying fan? How can religions arbitrarily assign souls to certain creatures, and not to others? As someone who views abandoned houses as living beings in a symbiotic relationship with their occupants, her anguish at the mundane cruelty of life is painfully poignant.

If the local authorities had paid heed to her warnings or replied to the numerous letters she sent to them, they would have found the killer fairly quickly. But the murders were acts of violence, requiring brute strength and material motive; something an ‘eccentric old woman,’ is less likely to understand. The motives that the police felt were integral to the investigation were nowhere near what caused the murders.

Things like attachment, emotion, love and passion; often synonymous with instability of the mind were what caused the murders, not money and mafia or human trafficking. In a world where women are defined by men, Janina wryly finds herself checking one box after the other of what it means to be mad; deviating from the socially accepted norms.