The way I perceive feminism or my idea of it has changed and evolved with age and time.

The unlearning and relearning process of social conventions has been crucial in understanding and becoming a feminist.

Feminism means dressing the way one wants to, having the authority over the choice of career, having the freedom to walk freely at night, etc. Being a teen girl residing in Delhi, the freedom to walk freely even in daylight, without the fear of being eve-teased. This was the vague comprehension of feminism I had perceived when initially introduced to the term, presumably in the higher secondary school, way ahead of the time I deconstructed the definition of feminism to understand it better.

Feminism is an ideology that advocates socio-political, economic, and personal equality of the sexes, where the sex assigned at birth does not stand alone as an individual’s identity but an overlap of other identities like caste, gender, class, sexual orientation, or religion, forms an individual’s intersectional identity. Depending on such intersectionality the need for feminism changes for a community or an individual. This is the volatile apprehension of the term feminism I have acquainted myself with.

As a Dalit cishet woman trying to conquer or have control over my mental health, I often attempt to reflect upon my identity. This, time and again takes me back to the timid little girl I was back in school in Delhi. Eve-teasing, passing on sexist comments, misogynistic gestures, and stalking have become normalised occurrences in Delhi.

When one such event or a series of such events take place it takes a toll on one’s mental health but for the perpetrators, it merely means establishing their dominance or superiority over and subordinating the other genders, generally a woman or other gender minorities in a patriarchal society.

It is typical of a Delhi Malayali to be a part of a Malayali organisation, and unquestionably my family has also been part of a few, celebrating our festivals together and sustaining one’s culture when uprooted from our native place. I often found solace and contentment while practising dance together for every other Kerala festival we celebrated and every other competition we participated in together.

We often practised at night, and when we did we would make sure to drop each other home safely, yet instances of stalking or eve-teasing would accompany us even when we were children. The fright intensified with the 2012 Nirbhaya gang rape case, which shook the entire country, with my obscure memory, I believe the 11-year-old me was terrified for weeks to months.

Dance has been an integral part of elevating my self-confidence and self-worth, and so has the Malayali community in forming my identity. Nonetheless, critically speaking often such communities do not exist in the absence of casteism, there are certain Savarna organisations namely the Nair Service Society(NSS), which create a bifurcation on a caste basis and creating a sense of hierarchy.

I remember an instance when an eleven or twelve-year-old I felt neglected and sidelined and wondered if I was not proficient enough to perform in an NSS event. I was oblivious to my caste identity or the term caste in itself then or even the Savarna identity of the NSS organisation.

To speak of one more such organisation the motto of which says, “Oru Jathi, Oru Matham, Oru Daivam Manushyanu,” which means, One caste, one religion, one God for humankind, even though I had performed in their events and celebrations, we were denied membership for the longest of time. The presence of such communities might create a sense of inferiority in children sidelined on a caste basis. Later on, I did learn that it was not me who was not proficient but the nature of such casteist organisations.

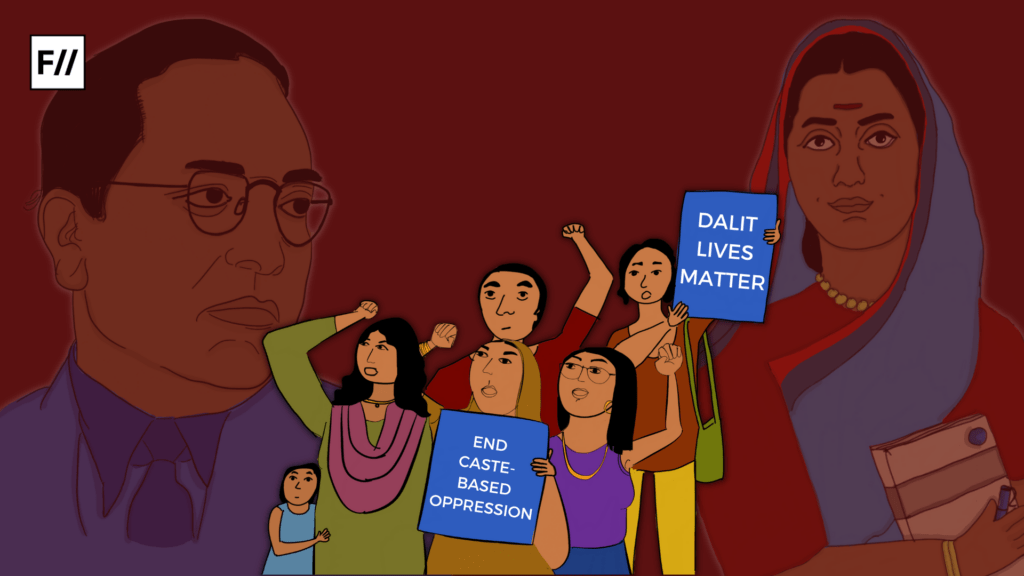

Understanding and acknowledging the intersectionality of feminism, the intersectionality of identities, minorities, and oppressions took an immense amount of time. It is a process of learning, unlearning, and relearning a lot of societal conventions. This process of relearning created instances where I contradicted my idea of feminism several times. This is when I came across the term Savarna feminism.

Savarna feminism is a feminist movement led by upper-caste Hindu women who exclude the needs of Dalit women or minorities much like the white feminists in the West. These are feminists who believe in reservation for women but against caste reservation. A pinch of subtle casteism can often be found when in conversation with them.

Such Savarna feminists are ignorant of the caste and religious minorities and this comes as a result of being blinded by the privilege they are born with and their internalised misogyny. While learning about this, I reflected on the absence of intersectionality in my idea of feminism, the lack of awareness about the double oppression faced by women belonging to religious minorities, the gender binaries, or the LQBTQIA+ communities, but I am attempting to read and understand it better.

Born into a family where patriarchy is almost invisible, I have always had space and authority over my choices. They have always supported my interest in dance, especially my father, whereas it had been different with my relatives. I have had to listen to comments such as, “Girls from good families do not dance after a certain age,” and I was only fifteen then. To this, my father replied, “My daughter has the right to choose what she wants, no one can tell her what to do.”

I have always had the privilege of being born into a supportive family and having a family who has always taken a stand for me. Often individuals are not given familial support for what they are, which can help in being less vulnerable.

Rani Mukjerjee’s controversial statement in Rajeev Masand’s The Bollywood Roundtable, “You have to have the courage to protect yourselves,” received an instant reply from Deepika Padukone, “There are women who are not constructed like that. They feel cornered.” This made a lot of sense to me.

Often in the instances when I have kept quiet while having faced eve-teasing, stalking, subtle casteism, or sexist comments even though I condemn the immoral act, I find myself on the weaker edge. Does it mean that you are not strong enough to be a feminist or are less of a feminist? It again took a lot of unlearning and relearning processes to understand everyone is constructed differently, you are caught in the thought of repercussions one may have to face if you retaliate against such acts, and sometimes you do not feel it is worth entertaining such people, sometimes you choose to take action. But none of the decisions one makes in a vulnerable situation make them less of a feminist.

One is not born a feminist but as mentioned before it is an outcome of the learning, unlearning, and relearning process. Attempting to comprehend the intersectionality of identities that one might have while also acknowledging the generational privilege one is born with and respecting the caste, class, gender, and religious minorities in the process and thereafter. It is important to be kind and respectful to the historically underprivileged communities and the privileges they are not born with and understanding oppression differs based on certain intersectional identities and lived experiences of a person. Thus, the need for feminism also differs for individuals or communities.

About the author(s)

Hrithika Haridas (she/her) is a final year MA Communication (Media Practice) student at the University of Hyderabad. She tries to look at things through the political, gender, class, and caste lens unlearning and relearning conventional normatives pushed on to us. She wants to be an inclusive content creator, inclusive of caste, class and gender minorities.