Marathi literature has been a pioneering force in the emergence of Dalit consciousness within the larger Indian literary landscape. It has given voice to the harsh realities and fragmented experiences of the oppressed Dalit community, challenging the hegemony of the upper-class and caste perspectives in literature.

The seminal work Jevha Mi Jat Charoli by Baburao Bagul, published in 1963, served as a watershed moment, offering a raw and uncompromising portrayal of the cruelties faced by the Dalit community. While the initial Marathi Dalit writers like Namdeo Dhasal, Daya Pawar, and others gave voice to the anger and sufferings of Dalit protagonists, the intersectionality of caste and gender oppression faced by Dalit women was not adequately addressed initially.

However, inspired by the pioneering efforts of social reformers like Dr B.R. Ambedkar and Mahatma Jyotiba Phule, who emphasised the need for education and empowerment of Dalit women, the Dalit women’s movement gained momentum. They asserted their agency and by claiming ownership of their narratives and identities, Dalit women writers and activists in the Marathi literary sphere played a crucial role in highlighting the intersectionality of caste and gender oppression, challenging the deeply rooted hierarchies and inequalities that had marginalised them for centuries.

Here is a list of must-reads on how gender and caste intersect in the Marathi literature.

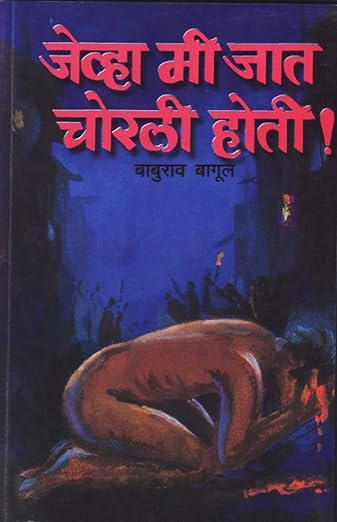

1. Jevha Mi Jat Charoli

Baburao Bagul’s collection of stories provides an unflinching portrayal of the dual oppression faced by Dalit women due to the intersecting forces of casteism and patriarchy. While some stories depict Dalit men rebelling against caste discrimination, it is the lived realities of the female characters that truly expose the intensified suffering at this intersection of marginalised identities.

Many of Bagul’s Dalit women characters are routinely sexually exploited and abused precisely because of their lowered caste status and resulting economic vulnerability. Pesuk reveals how Dalit women are forced into sexual servitude to dominant caste men’s desires, only to be subsequently outcasted as immoral while their abusers go unpunished.

Narratives like Prisoner of Darkness and Streetwalker depict how motherhood for a Dalit woman is rarely a celebrated condition, but rather an imposed state of being – the result of rape, coerced relationships, and an oppressive caste system.

Furthermore, Bagul’s writings portray how the intersecting forces of casteist and patriarchal violence across generations have utterly crushed the spirits of Dalit women. Their everyday acts of resilience and recreation are largely obscured by the brutal narratives of victimhood and destitution they are compelled to endure.

In Monkey, the protagonist, a Dalit woman gets lost in the whirlwind of domestic violence perpetrated by both her husband and her mother-in-law. By centring his Dalit women characters’ lives at this painful intersection of gender and caste, Bagul exposes how they face amplified and uniquely oppressive circumstances compared to Dalit men or upper-caste women.

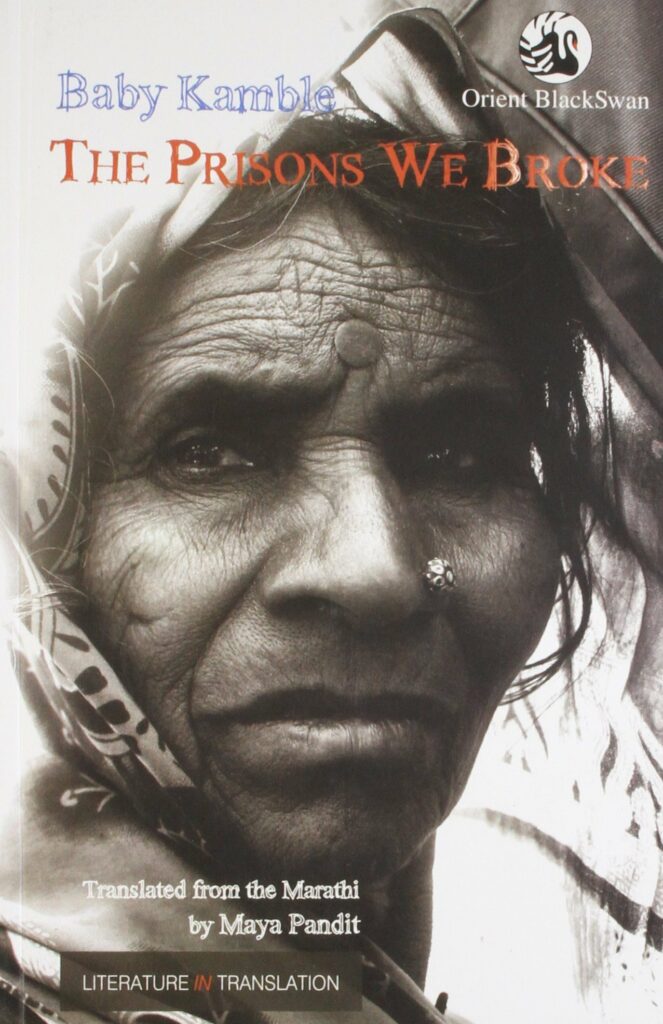

2. Jina Amucha

Babytai Kamble’s Marathi autobiography Jina Amucha is acclaimed as the first autobiography by a Dalit woman writer in any language. More than a personal narrative, it provides a sociological account of the lives and struggles of the Mahar community, especially Mahar women. The text exposes the dual oppression arising from the intersecting forces of caste and patriarchy.

Kamble chronicles how Dalit bodies and lives were dehumanised by the ancient caste hierarchies promoted by Brahminical Hinduism. The horrific conditions, poverty, and deprivations faced by Mahars, treated as subhuman and untouchables, are vividly depicted. Kamble unsparingly also documents the physical and psychological violence inflicted on Dalit women in public and private spheres by casteist and patriarchal norms.

Within their homes, young Dalit brides were viewed as commodities, subjected to abuse from not just husbands but also mothers-in-law. She also briefly mentions how in her school, the girls from the Mahar community including herself had to squat on the floor while the other dominant caste girls had benches to sit on. From receiving basic education to draping the sarees, the women and girls from her community were discriminated against.

Additionally, economic deprivation combined with regressive traditions around pregnancy, childbirth, and superstitions made their lives more oppressive. Kamble thus, critiques how upper-caste Hindu women, though privileged, also actively upheld casteist practices and the notion of ritual pollution against Dalit women. However, the autobiography stands as a testimony to the Dalit women’s growing consciousness, organisation, and struggles inspired by Ambedkar’s liberatory vision and activism.

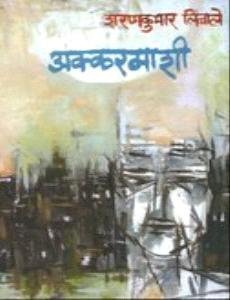

3. Akkarmashi

Akkarmashi offers a searing critique of the hypocritical attitudes and practices of upper caste-Hindus towards Dalits, especially Dalit women. Sharankumar Limbale documents instances where Hindus worship the cow as a mother but have no qualms in relying on Mahars (whom they consider inferior to the animals) to dispose of dead cow carcasses.

Limbale’s narrative highlights the double marginalisation faced by Dalit women, who are oppressed not only due to their caste identity but also due to their gender. He portrays Dalit women as mere objects of pleasure, toys for upper-caste men to exploit without any regard for their dignity or consent. Particularly, Masamai, Limbale’s mother, is depicted as a victim of the patriarchal and casteist social structure. She is sexually exploited by upper-caste men, forced into extramarital relationships, and ultimately abandoned by her children. The narrative also delves into the experiences of Limbale’s grandmother, Santamai, and his sisters, Nagi and Nirmi, depicting the intergenerational cycle of oppression and marginalisation faced by Dalit women. The lack of education, child marriage, and denial of basic rights are highlighted as factors that perpetuate the subjugation of Dalit women.

The novel thus, serves as a scathing indictment of the deeply ingrained prejudices and discriminatory practices that relegate Dalit women to the lowest rungs of the social order.

4. Aaydan

Aaydan offers a poignant narrative of the intersectional oppression faced by Dalit women in India. Through vivid personal accounts, Urmila Pawar unveils the harsh realities of growing up as a Dalit woman, where caste and gender-based discrimination converge to create a relentless cycle of marginalisation. Pawar’s life journey, woven like the bamboo baskets her mother crafted, is a tapestry of struggles against poverty, untouchability, and patriarchal subjugation. From her childhood experiences of being barred from community activities and ridiculed for her hunger to the sexual exploitation she endured, the memoir exposes the pervasive dehumanisation of Dalit women.

The author’s reflections on her marriage and professional life highlight the persistent challenges faced by Dalit women, even after attaining education and financial independence. The denial of her pursuit of higher education and the expectation to conform to traditional gender roles within her marital home underscore the deep-rooted patriarchal mindset that permeates society.

Pawar’s narrative is a powerful testament to the resilience and determination of Dalit women in their quest for dignity and self-realisation amidst the intersecting forces of casteism and gender-based oppression. Aaydan serves as an urgent reminder to dismantle these oppressive structures and ensure equal rights and opportunities for all individuals, regardless of their caste or gender.

5. Antasphot

Antasphot, through nine poignant testimonies, reveals the enduring presence of gender and caste discrimination in Indian society. Kumud Pawade’s narrative highlights the intersecting oppressions faced by Dalit women, who are doubly marginalised due to both caste and gender.

Pawade observes a categorical lack of sensitivity towards issues faced by poor, rural Dalit women within the Dalit movement itself. From her childhood experiences of being ostracised by dominant caste peers to the discrimination she faces even after marrying outside her caste, Pawade exposes the deep-rooted prejudices prevalent in Indian society.

Moreover, Pawade delves into the patriarchal norms that restrict women’s autonomy and perpetuate oppressive rituals like the Savitri Vrat to the Caste biases that prohibit lower castes from learning Sanskrit (considered a sacred language, hence only to be used by Brahmins). She challenges the societal expectations imposed on women and advocates for their empowerment through education and resistance against oppressive customs. Nonetheless, despite facing ridicule and discouragement, Pawade’s narrative serves as a rallying cry for Dalit women’s empowerment and societal reform rooted in the principles of Phule and Ambedkar. Through her autobiography, she urges for a transformation in the collective consciousness, envisioning a society free from the shackles of caste, class, and gender oppression.