The recent Supreme Court judgment regarding the sub-classification of Scheduled Castes (SC) and Scheduled Tribes (ST) represents a crucial moment in the discourse surrounding affirmative action policies in India. This decision, rendered by a seven-judge bench led by Chief Justice D.Y. Chandrachud, and comprising Justices B.R. Gavai, Vikram Nath, Bela M. Trivedi, Pankaj Mithal, Manoj Misra, and Satish Chandra Sharma, held by a 6-1 majority that allows for the sub-classification of SCs and STs to create separate quotas for more marginalised groups within these categories. Justice Bela Trivedi dissented from the majority opinion.

Overview of the judgment

On August 1, 2024, the Supreme Court ruled in a 6-1 majority that states have the authority to identify and classify various groups within the SC and ST categories based on their levels of backwardness. This ruling effectively overturns the previous 2005 judgment in E.V. Chinnaiah v. State of Andhra Pradesh, which had determined that SCs and STs constituted a homogeneous group that could not be further subdivided for the purposes of reservations.

The bench’s decision was based on two primary questions:

- Whether sub-classification among reserved castes is permissible.

- The validity of the E.V. Chinnaiah judgment, which had previously established that SCs were a singular, homogeneous group.

The majority opinion articulated by Chief Justice Chandrachud emphasised that the historical context of caste in India demonstrates that SCs are not a monolithic group. The judgment highlighted that sub-classification does not infringe upon the principles of equality enshrined in Article 14 of the Constitution, nor does it violate Article 341, which outlines the powers of the President to notify Scheduled Castes.

Implications of the ruling

The ruling has significant implications for the implementation of affirmative action policies across states. It empowers state governments to tailor their reservation policies to better address the disparities among different groups within the SC and ST categories. Chief Justice Chandrachud noted that the systemic discrimination faced by members of these communities often prevents them from progressing socio-economically.

Thus, the court’s decision aims to provide preferential treatment to those who are more disadvantaged within these groups. Justice B.R. Gavai; the only dalit judge on the bench, reinforced the necessity of preferential treatment for the more backward classes, asserting that the existing reservation benefits have not reached all members of SC/ST communities equally.

Historical context of caste subcategorisation and legal precedents

The backdrop of this ruling includes a history of legal challenges surrounding the classification of SCs and STs. The initial resistance to sub-classification stemmed from the E.V. Chinnaiah case, which posited that the designation of SCs under Article 341 created a single, unified category.

The case that led to this significant ruling originated from the State of Punjab v. Davinder Singh, where the Punjab Scheduled Caste and Backward Classes (Reservation in Services) Act, 2006, was challenged. This act sought to allocate a portion of the SC reservation to specific groups, namely Balmikis and Mazhabi Sikhs, which had been invalidated by the Punjab and Haryana High Court based on the Chinnaiah precedent. The Supreme Court’s ruling now reinstates the validity of such provisions, allowing states to implement similar measures to address the needs of the most marginalised within SC and ST communities.

Potential problematics concerning the sub-classification of caste

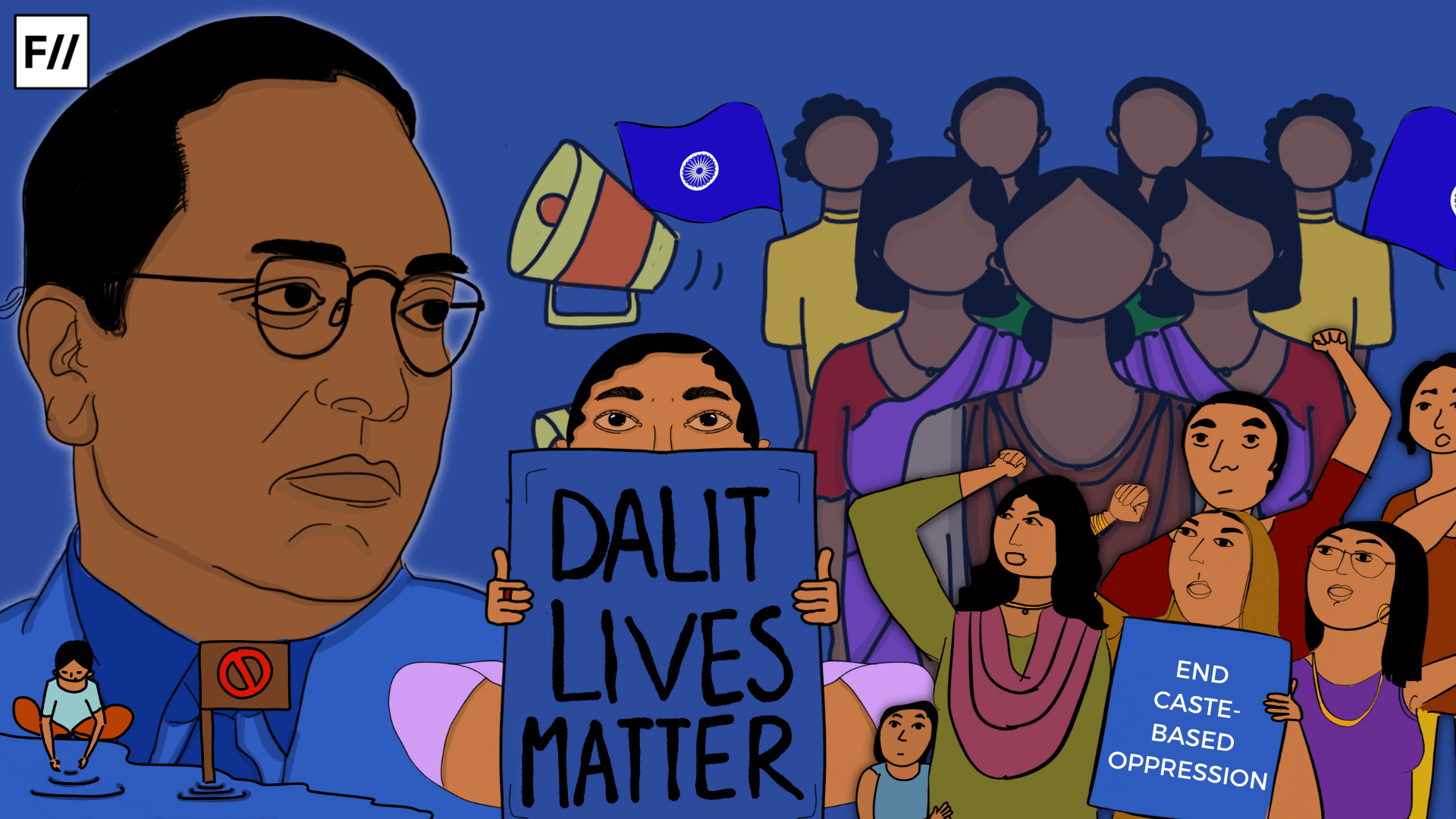

Babasaheb, while drafting the constitution and laying the foundation of the reservation system in independent India, did not provide any provision of the sub classification of Scheduled Castes. The reservation policies were introduced keeping the historical marginality at their core. Dalits, as a whole community, were considered untouchables and no subcategory was exempted from this discriminating practice. Sub-caste reservations may deviate from Babasheb’s all-inclusive vision for addressing caste-based inequalities.

Sukhadeo Thorat, former chairman of UGC and professor emeritus at JNU, views the academic basis for sub-caste reservations as weak, for the under-representation of certain sub-castes is more likely due to a lack of income-earning assets and education rather than discrimination by other SC sub-castes. For him, implementing sub-caste quotas without rigorous academic justification and factual data may fail to address the root causes of disparities.

This also raises an important question on the Indian State’s approach towards the functioning of the existing provisions of reservation and affirmative action policies.

This also raises an important question on the Indian State’s approach towards the functioning of the existing provisions of reservation and affirmative action policies. The recent introduction of EWS reservation by 103rd constitutional amendment act of 2019, various states; like Karnataka and Madhya Pradesh, diverting the SC/ST welfare funds for other activities, limiting the scholarships for SC/ST students are a few of the setbacks that reflect the indolence of the Indian State in favor of individuals from the dalit and tribal community.

The elongated-generational discrimination against the communities cannot be merely undone by providing government jobs to two or three generations. Historical discrimination cannot be only viewed through the lens of occupation and economics. Caste-based discrimination also severely affects the dietary habits, capital ownership, social capital, educational participation, and physical features of individuals in a community. The apex court hardly delved into the prospects of sociology.

The reason for the most disadvantaged SC community not being able to vitalise the reservation yet is not simply the active participation of the dominant community. It has largely to do with the unavailability of basic resources and amenities (such as water, food, livelihood, education) to such communities. And, if sub-caste reservations are implemented without improving capital ownership and educational participation, the problem of under-representation may persist. The relatively better-off sub-castes may continue to have an edge in accessing jobs and education, while the more disadvantaged individuals within sub-castes may still lack the necessary capabilities.

Affirmative action policies, in place for a mere 75 years, cannot be expected to counterbalance centuries of entrenched discrimination. Economic mobility alone does not erase the deep-rooted stigma associated with caste. The superficial metrics of progress often fail to address the underlying social prejudices and barriers that continue to disadvantage dalit and tribal communities.

Impact on Dalit and tribal women

The decision to permit sub-categorisation within Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes for reservations is poised to have severe repercussions on the mobilisation of Dalit and tribal women. Historical evidence portrays that the introduction of creamy layer (Indra Sawhney vs Union Of India 1992) of Other Backward Classes (OBCs) did not majorly affect the male from the creamy layer and landed communities from amassing material wealth and maintaining a dominant social image. In contrast, women within these groups were largely left to navigate the confines of household duties and family issues.

Dalit and tribal women, who already face multiple layers of marginalisation, risk being further sidelined by sub-caste reservations.

Dalit and tribal women, who already face multiple layers of marginalisation, risk being further sidelined by sub-caste reservations. These women are often the most disadvantaged within their communities, facing barriers not only from broader societal discrimination but also from patriarchal structures within their own groups.

Supreme Court’s perspective on homogeneity

Chief Justice of India Dr. D.Y. Chandrachud, in his verdict, emphasised that Scheduled Castes (SC) are not a homogeneous group. However, he overlooked the striking homogeneity within the office of Justices and Chief Justices of India. Since independence, the country has seen only one Dalit CJI, K.G. Balakrishnan, and scarcely any individual from a tribal background occupying this highest office. This systemic discrimination within the judiciary itself has been largely ignored by the Supreme Court.

Justice Pankaj Mithal’s unusual judgment

Justice Pankaj Mithal’s judgment in the ruling is notable for its unusual focus on the desirability of reservations as a tool for empowering backward communities. This focus diverges from the core issues presented in the litigation. Justice Mithal advocated for a ‘fresh re-look‘ at the policy of reservations, suggesting that alternative methods should be developed to uplift the depressed classes. He proposed that any facilities or privileges aimed at promoting these groups should be based on criteria other than caste, such as economic status, living conditions, and vocational factors.

In another controversial assertion, he argued that reservations should be limited to the first generation of beneficiaries, suggesting that periodic reviews should exclude individuals who have benefited from reservations and have subsequently achieved parity with the general category. Such a statement in the judgment vividly portrays the negligence and hypocrisy of a savarna Judge; for Justice Mithal is a grandson of a lawyer, son of an ex-permanent judge of Allahabad High Court. His lineage privilege also allowed him to distinguish between Caste System and Varna System in his observation.

Introduction of creamy layer with the scheduled caste and scheduled tribes

The judgments by justices Gavai, Nath, Mithal and Sharma also mentioned about the application of the creamy layer principle to the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes. This was unexpected because it was not a topic of dispute or included in the issues that the court was set to resolve. By suggesting that economic status should dictate eligibility for reservations, the court risks undermining the fundamental essence of affirmative action, which is rooted in the socio-cultural identity of caste rather than mere economic mobility.

Caste is not merely a reflection of financial standing; it embodies a complex historical legacy of oppression and discrimination. The idea of introducing a creamy layer within SC/ST categories threatens to dilute the very purpose of reservations, which aim to provide social justice and rectify centuries of systemic inequality. Even today, the representation of SC/ST populations in various sectors remains significantly inadequate, and the proposed changes could amplify this underrepresentation rather than alleviate it.

Even today, the representation of SC/ST populations in various sectors remains significantly inadequate, and the proposed changes could amplify this underrepresentation rather than alleviate it.

The bench’s perspective clearly appeared to reflect a Brahminical viewpoint that fails to adequately address the ongoing systemic oppression faced by SC/ST communities. Reservation is not a poverty alleviation plan rather it is a dignity alleviation plan. Every individual from a historically marginalised community requires reservation to fight the oppressive Brahminical State structure. Rather than limiting or sub-classifying the reservation policies, the apex court should aim to scrap the inherent caste based practices from every dimension of Indian society, which would eventually lead to the scrapping of reservation.

About the author(s)

Harsh Bodwal teaches Social Science and English at a CBSE-affiliated school and holds an MA degree in Political Science from Jawaharlal Nehru University. His research explores how caste, patriarchy, and capital intersect with the various institutions to shape and often constrain democratic processes.