Anne Bronte was the sixth and youngest child of Patrick Brontë and Maria Branwell Bronte. She was born in Thornton, West Yorkshire, and grew up in the parsonage in Haworth.

Anne Bronte was the sixth and youngest child of Patrick Brontë and Maria Branwell Bronte.

The Brontë children were awfully affected by the early deaths of their mother and two older sisters, Maria and Elizabeth, leaving them in a small, isolated household with their father, a clergyman, and their brother Branwell, who was a sensitive little child and later on developed a terrible addiction to alcohol, which often left him in a great deal of pain.

The Bronte children were close-knit and developed a vivid imaginary world. Anne and Emily created the fanciful word of Gondol and Angria, rich with fantasies and intertwined with what little they must have understood of politics as children.

Anne as a writer

Anne, like her sisters, was educated at home, where she and her siblings read widely and wrote stories and poems together. In 1839, nineteen year old Anne found employment at Blake Hall near Mirfield. Unable to wield control over unruly children, she was soon dismissed. This trying time is supposedly the basis of her first novel, Agnes Gray, supposedly extravagant, but with scenes of morbid love.

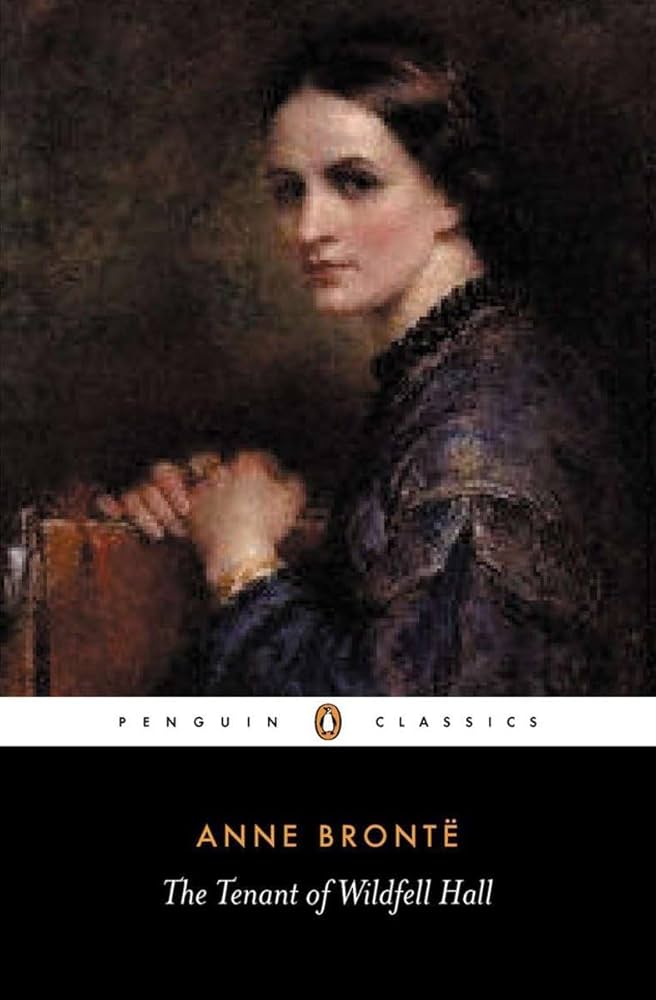

Anne’s second novel, The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, is far bolder in its social critique. It tells the story of Helen Graham, a woman who leaves her abusive, alcoholic husband to live independently with her son. The novel deals directly with issues such as addiction, domestic abuse, and the limited options available to women in Victorian society. It was scandalous for its time, due to its frank treatment of alcoholism and marital abuse. The novel is often considered one of the first feminist novels, as it questions the institution of marriage and the oppressive expectations placed on women.

Anne’s legacy

Anne Bronte died at the age of 29 from tuberculosis, just a year after the publication of The Tenant of Wildfell Hall. Whilst she never achieved the same level of recognition as her sisters (Emily and Charlotte Bronte are known by almost everyone acquainted to British literature even today), and while her books were not as revolutionary in their narrative style (possessing neither Emily’s dramatic atmospheric charm that threatens to ravage your insides nor Charlotte’s spiralling interior monologue), they are remembered for being one of the first novels with such a strong proto-feminist character.

Her characters deal with morality and she was one of the first to talk about an abusive relationship, and the happiness a woman can experience when she flees from such a situation instead of trying to modify herself according to her husband’s pain.

In her preface to the second edition of The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, Anne is bold in stating, ‘I know that such characters do exist, and if I have warned one rash youth from following their steps, or preventing one thoughtless girl from falling into the very natural error or my heroine, the book has not been written in vain. All novels are or should be for both men and women to read.’

Interestingly, Anne was the most religious of the Bronte sisters and she had seen horrible consequences of abuse, alcoholism, infidelity and addiction. She used her experience and penned it all down. The novel was met with immediate success but of course, people were also shocked and scandalised about what she had written (all topics considered fairly taboo in nineteenth century England.)

The Tenant of Wildfell Hall is also fairly accessible, perhaps the easiest to read of all the Bronte books.

The Tenant of Wildfell Hall is also fairly accessible, perhaps the easiest to read of all the Bronte books. It opens with a young man, Gilbert Markham being fairly grumpy about the life he has to live and the job he has to do till his interest is piqued whilst his mother and sister and talking in hushed tones about a young seemingly bold but mysterious woman who has occupied a house that has long been dilapidated.

Comparison to her sisters

While Charlotte and Emily Brontë often dealt with more grandiose themes of passion, love, and personal freedom (sometimes in a highly idealised or fantastical way), Anne’s works tend to be more grounded in the social realities of her time. Her novels are less emotionally tumultuous than Wuthering Heights or Jane Eyre, and they often engage directly with the struggles of everyday life—especially for women in a patriarchal society. Her focus on the female experience, especially the often-overlooked lives of women like governesses, makes her works particularly relevant to feminist literary criticism.

Though Anne’s works were initially less popular and less well-reviewed than those of her sisters, her contributions are increasingly appreciated in the context of 19th-century social reform, feminism, and literature that speaks to the experience of women struggling for autonomy.

About the author(s)

Treya covers art, culture, climate and the environment. She has aspired to be a journalist ever since she was little. She has reported for The Hindu and Deccan Chronicle among others and explores how feminism takes root in everyday life by leading sessions with young people on gender, digital safety and the "good girl" syndrome.