The 2013 riots in Muzaffarnagar were a terrible episode in the series of communal riots in Independent India and more so in Uttar Pradesh. The riots began in August 2013, after a sequence of events that fueled interreligious animosity in a part of the country that has a reputation for ethnic diversity. The cause was a violent clash in one of the villages called Kawal where two young Hindus- Sachin and Gaurav were killed after allegedly assaulting a Muslim youth named Shahnawaz. This single event started a chain of violence driven by fake news and social media mobilisation which escalated riots in Muzaffarnagar and its neighbouring areas.

The violence resulted in the death of 62 people which included 42 Muslims and 20 Hindus; besides, more than 40000 families have been left shelterless. The aftermath was characterised by scenes of devastation: destroyed homes, suffering individuals and affected communities, and shelter that was inadequate for these numbers. Some Muslims migrated in search of safety elsewhere other than their ancestral homes while some were forced to stay behind to feel the impact of this inter-communal violence.

Displacement and long-term impact on Muslim communities

Many Muslims had to flee during the riots and even at present, they are not able to go back. Muslims originally populated some villages which are now empty. Muslims now only have remnants of the structures that used to be occupied by them. Even now after over a decade displaced persons still have psychologically overpowering effects from the riots.

Mehmood, a former resident of Kutb, poignantly reflects on his lost home. ‘We never imagined that our house would be attacked.’ He further says; ‘On 7 September 2013 at around 11 am some Jat community residential people attended a Maha panchayat in Nagla Mandore. In this Maha panchayat, the public was provoked and consequently, the violence spread to the whole area in districts Muzaffarnagar and Shamali. Mainly the village Kutba was targeted by the mob in which the houses of Muslims particularly Sirajuddin and Zahoor were set on fire. Eight Muslims were murdered and some others were injured in the attack. The rest of the near about 300 Muslims anyhow took shelter and hid themselves and another day in the early morning escaped and the police protected some of them. The Muslims anyhow reached the nearby town of Shahpur where they are now rehabilitated by the Islamic NGOs like Jamiat Ulama-e-Hind.’

The Akhilesh Government gave Rs 5 lakh in compensation for every family who lost their belongings and ran away due to the orders of the government. This money was used by most people who migrated to and purchased land to develop houses in new regions. This compensation was not sufficient to make a new home so Muslim NGOs like Jamiat Ulama-e-Hind contributed to the residential settlement.

Mehmood says, ‘I don’t want to return with my family. It’s very heartbreaking to leave your ancestral home.’ During the riots, the whole minority population left the village, and they never came back.

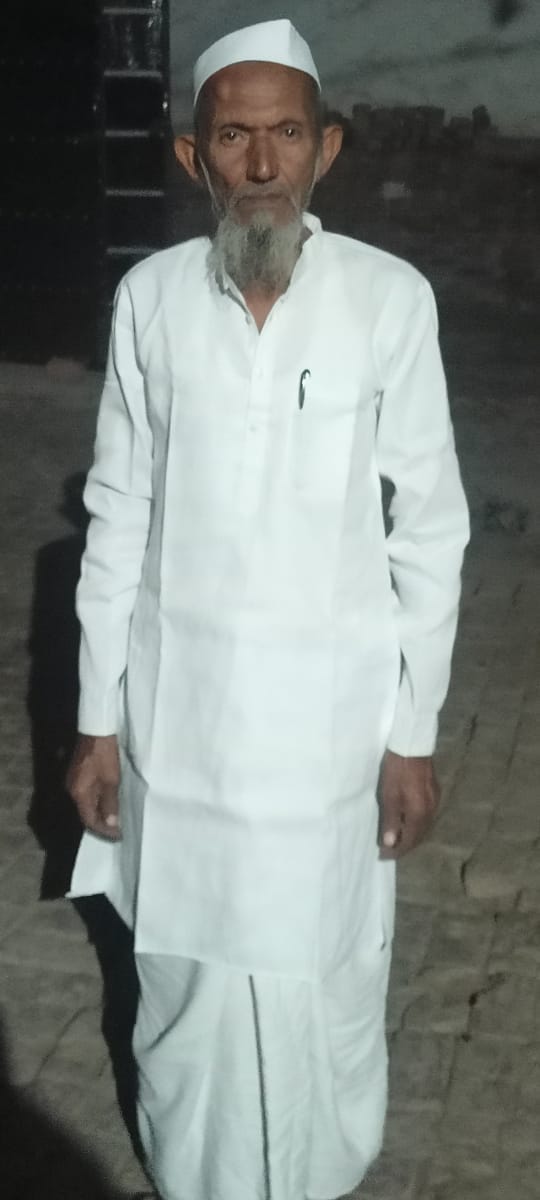

Mehboob a former resident of Kutbi village expressed his sorrow and grief. He was pushed to escape from his native place. He was economically frustrated and is still surviving in a severe situation. Even he is not in a position to afford the fees of their children to educate them. He is feeding the seven members of the family including his mother, his wife and children. He is still mentally distressed due to the havoc of communal riots which occurred without any proper reason and cause.

Subeideen, a victim of the Muzaffarnagar and Shamali riots, claimed that 600 Muslim families lived in Lisad, with some migrating and others being slain by rioters. Rioters lit up a huge fire. Some people were set on fire, along with their animals and household. They looted their houses. Many families fled through agricultural areas to Kandhala, a nearby town with an Eidgaah, where they were protected by Muslim and secular communities.

The Akhilesh government provided compensation of Rs 5 lakh to each household harmed by the riots. Subeideen never returned to Lisad owing to fear. Subeideen stated that riot cases are still pending in courts and that justice has yet to be served.

The unfulfilled hope of return and healing

Even after decades past the event in question, one cannot help but observe that recovery and therapy from the Muzaffarnagar riots have not happened fully till now. Especially thousands of people who had the biggest displacement and not only physically lost their homes but also the social connectedness within their societies or communities.

The narratives from people like Mehmood, Mehboob and Subeideen are mere replicas of a tragic story of loss which is accompanied by the infamous search for home. They pointed out that, even though homelessness and house demolishing remained potent issues, refugees now not only want houses back but, more importantly, to gain their feeling of belonging which had been shaken.

All of these concerns can only be addressed by the admission of fault, as well as measures to reconcile impacted ethnic groups and reconstruct the broken bridge in order to restore ethnic harmony. Only then can we work towards a future in which analogous horrors do not reoccur, as is essential for a healthy society.

About the author(s)

Ainee Ilyas is a writer and researcher with a strong foundation in law and human rights, specializing in the intersections of gender, social justice, and public policy. Passionate about feminist thought, her work amplifies marginalized voices and challenges conventional narratives. With experience in editorial writing, policy analysis, and rights-based research.