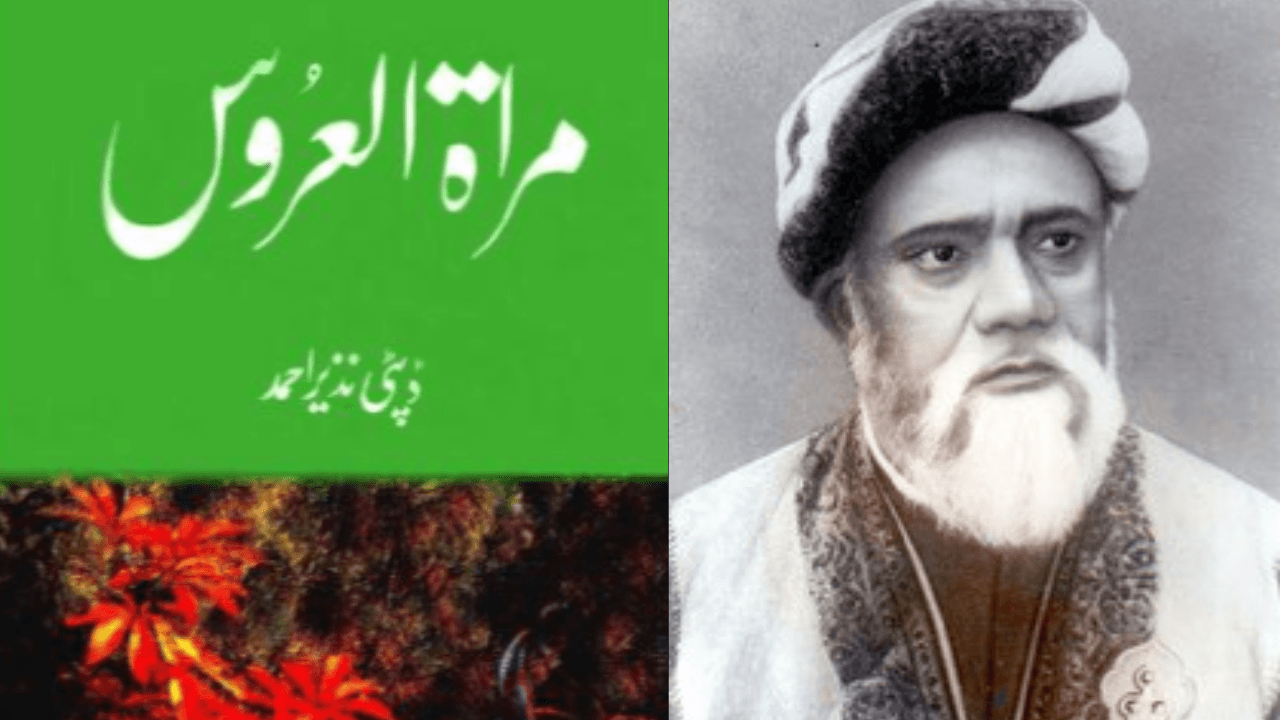

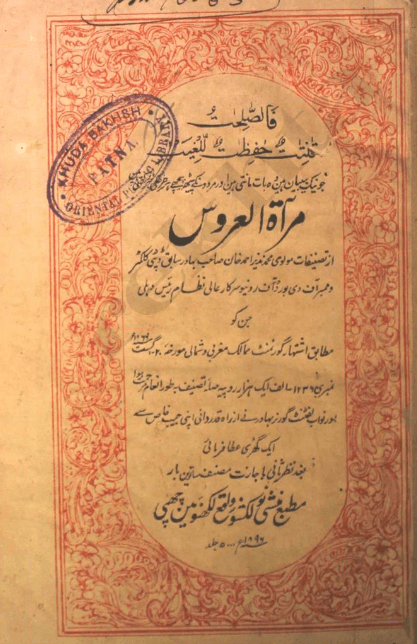

Women and their representation in literature have long remained interconnected. But it is more significant to take into account how they are perceived in literary works. In reference to Mirat-ul-Uroos, a nineteenth-century work of Maulana Nazir Ahmad Dehlavi, it is consequential to delve deep into limitations imposed on women.

According to Rekhta, he is well-known to have been the first Urdu novelist in India and who even talked about women. However, it is important to grasp his outlook on a specific section of Muslim women and his attempt to maintain their centuries-old confinement to household activities.

Through the Mirat-ul-Uroos, Ahmad propounded the concept of an ideal Muslim woman, and in the introduction, he seems to be authoritative, which means there is a voice of judgement that even gives instructions that education should be given to women, but not too much; they can write letters, keep records, raise children, and be submissive to husbands and in-laws. According to him, education is for women to assist men and maintain household management.

In simple words, such education is called home-bound education. This is not meant for their upliftment from the invisiblisation and margins, but to sustain their submission. It is more about maintaining their household arrangements. More importantly, the education is confined to upper-class-caste Muslim women who are considered the honour and dignity of shareef or respected families.

Home-bound education and its nexus with a Shareef Gharana

Well, home-bound education and its nexus with a ‘Shareef Gharana‘ were taken up in the nineteenth century. In line with gender roles, a clear distinction was made between home-bound education and formal education. The former was for women, and the latter was for men. Those who are credited to have pioneered serving modern education to Muslims in the nineteenth century could not acknowledge the need for educating women beyond traditional bounds.

Though women had long been deprived of education and had been expected to be confined to home, Nazir Ahmad could not tackle the actual socio-economic deprivation at the time. When he decided to give up on the traditional course for girls, Mirat-ul-Uroos was written as a training guide for them. It was indeed a guide, but for upper-caste girls, lowered-caste children were still overlooked. The home-bound education for girls hailing from ‘Shareef Gharane,’ or respected families, was given more attention.

Nazir Ahmad and his contemporary, Sir Syed Ahmad Khan, who influenced him to a great extent, are regarded to have pioneered the modern education revolution among Muslims and maintained the same confinement. Ahmad Khan adopted a traditional approach when it came to educating women. He did not want to impart modern education to women to gain freedom. He preferred to hold on to the traditional home-bound education for women.

In the midst of Ahmad Khan’s ardent supporters, Sheikh Abdullah emerged to be his critic in his autobiography “Mushahidat Aur Tassawurat” (Observations and Impressions, 1969). He affirmed that there was no existence of modern education for girls in the second half of the nineteenth century, and Ahmad Khan did not want it to be imparted to women. Other critics are Gail Minault and David Lelyveld, who asserted their unwillingness to acknowledge the rights of women preached by Islam.

Well, both male and female students at Aligarh Muslim University appreciate Ahmad Khan for his pioneering contribution to imparting modern education among Muslims on the occasion of Sir Syed Day. But its limitations should be taken into consideration. There is a lack of extensive research studies to be taken to understand his male-dominated willingness.

The paradoxical theme of the novel is relevant in present-day society

In accordance with Nazir Ahmad’s profile on Rekhta, his work is considered relevant in present times. The novel embodies the paradoxical characters of Akbari and Asghari. The former is a non-conformist who is criticised for expressing her willingness to live her life, challenging societal expectations, and making associations with people who are seen as belonging to non-respected families or lower strata. The latter is a conformist who is appreciated for maintaining household management through her education and even opens a school where she refuses to teach lowered caste children.

To be more precise, it is still relevant on the grounds of complying with societal expectations about educated men and educated women. Educated men should provide shelter and protection to women, and educated women should look after household management.

In the present time, ‘motherhood‘ and ‘idealisation‘ are embraced. ‘Who an ideal man is‘ and ‘Who an ideal woman is‘ is instructed. The ideal woman is looked upon as raising ideal children and remaining submissive to male members and confined to the private domain. This is one of the major factors for the low literacy rate among Muslim women in India.

Mirat-ul-Uroos can be used to understand the marginalisation of women

The nineteenth-century novel holds relevance in the present time. It should be used to understand the question of marginalisation of Muslim women. In adherence to a research study done by Firdaus Bano in 2017, “Educational Status of Muslim Women in India : An overview,” Muslim women in India are vulnerable to educational backwardness. Muslims could not be able to decipher the association between education and socio-economic upliftment. The calibrated maxim ‘Education for All‘ is crystalline to everyone, but its implementation still remains impractical.

It is veracious to accept that governmental outreach as invisible, but we should not fail to admit social norms that made Muslim women backward in education. Education breeds freedom, which is perceived to be detrimental to well-established male dominance. This is the first and foremost reason that is put forward when it comes to imparting education to Muslim women. The most important thing is that educating Muslim women is a step towards raising concerns about their rights.

The Sachar Committee was set up to look into the socio-economic and educational status of Indian Muslims. It came up with its report that asserted only 4 percent of Muslims are educated. But it gets worse pertaining to Muslim women, who are even behind Muslim men in education. Though there are other factors as well to halt the marginalised from attaining educational enlightenment : parental preference given to boys over girls due to economic constraints, long distances from educational institutions, poor transportation, poor infrastructure, etc.

About the author(s)

Nashra Rehman finds her profound interest in addressing the plight of Muslim women and their unappreciated marginalisation. Her focus remains on bringing a novel argument to life.