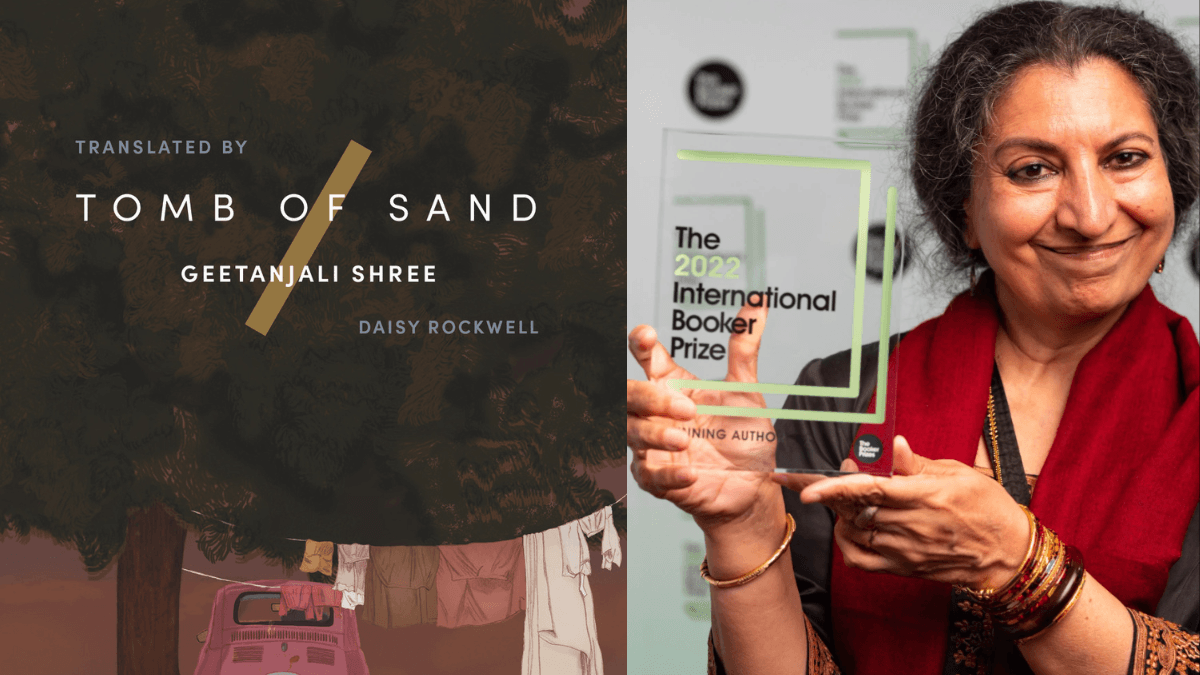

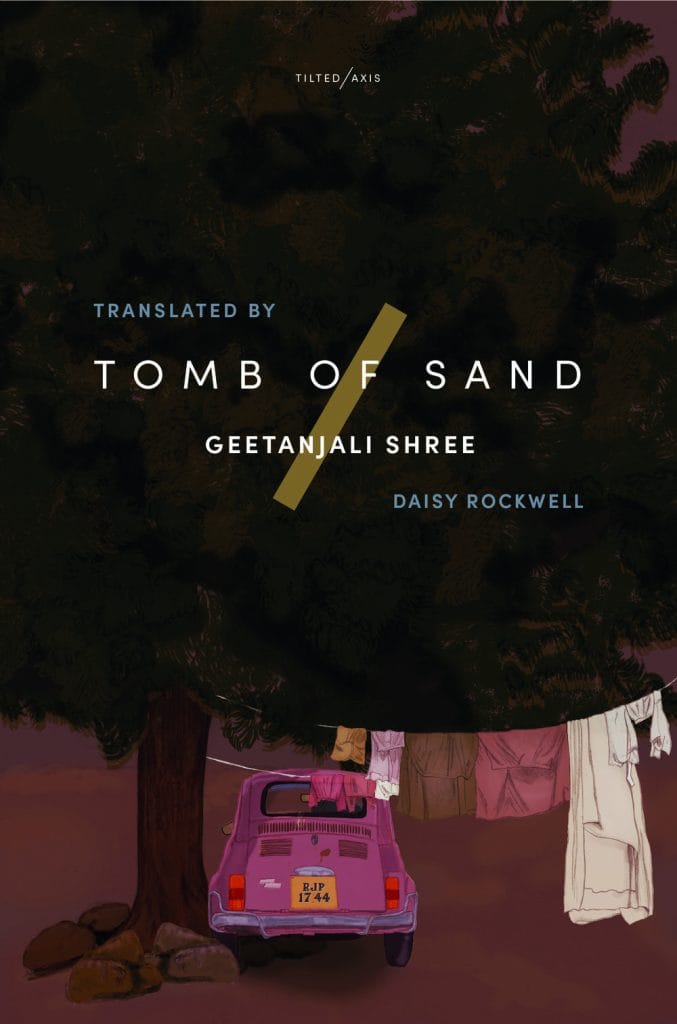

In Tomb of Sand, Geetanjali Shree’s Booker Prize-winning novel, we meet an 80-year-old woman who refuses to be what society expects her to be. She steps out of mourning after her husband’s death—not into quiet resignation but into a whirlwind of rediscovery. Translated from Hindi by Daisy Rockwell, this book is not just a story—it’s a reclamation. Of memory. Of movement. Of womanhood. The book cleverly covers themes like widowhood, gender norms, Partition, ageing, queerness, and friendship.

At its heart, Tomb of Sand is a radical refusal. It challenges the tomb-like roles women are buried in—across age, borders, caste, and patriarchy—and gently but firmly digs them out, revealing a woman who dares to begin again.

Eighty, not done: Rewriting age and gender

Most Indian stories about older women tend to tuck them away into the corners—caring for grandchildren, resigned, and wrapped in holiness. But Ma, the unnamed protagonist of this novel, refuses this script. After her husband dies, she slips into depression—but then emerges, quite literally, by turning her back to the world and walking into a new one.

Through Ma, we get to realise that agency never retires. Age does not steal away a woman’s right to rebel or explore her desires, complexities or opportunities. In fact, it may as well sharpen them. This dynamic is particularly important for the Indian context, where older women are often seen as symbols of sacrifice and silence.

Ma chooses travel over tradition, friendship over family expectations, and her path over the well-worn one. In doing so, she reclaims her body and spirit from a society that had long stopped expecting her to have either.

Gendered trauma and historical borders

One of the most striking parts of the novel is its profound engagement with the Partition of India—a violent, unfinished wound in our history. But Shree doesn’t treat Partition like a historic event to be archived. Instead, she brings it into the everyday—into a woman’s memory, into her guilt, her silences, and ultimately, her return.

Ma travels to Pakistan late in the novel, not as an act of nostalgia but as a way to confront her past—a past that involves a deeply personal trauma, one tied to both violence and survival. This journey is not just across geographical borders but also across emotional and historical silences.

Partition, in this story, is not just political. It is gendered. Women bore the brunt of displacement, abduction, rape, and shame during 1947. Ma’s return to Pakistan as an old woman is her way of reclaiming not just her story but all the stories of women whose lives were never considered worth recording.

Friendship as feminist resistance: Ma and Rosie Bua

A major relationship in the book is between Ma and Rosie Bua, who becomes her closest companion. This friendship is radical—not because of the identities involved, but because of how ordinary, loving, and respectful it is. They walk, talk, share food, laugh, and explore the city like two young girls discovering life for the first time.

In this friendship, we see how solidarity can exist across margins—between an elderly upper-caste woman and a trans person often cast out from both gender and caste hierarchies. Rosie is not treated as comic relief or a token. She is given depth, kindness, and dignity. Their bond is a quiet act of resistance to the norms that society holds up.

This is intersectional feminism in action—not in theory, but in tea and shared silences, in second chances, and in shared struggles.

Telling women’s stories on their own terms

One of the most beautiful things about Tomb of Sand is its language—both in the original Hindi and in Daisy Rockwell’s sensitive, lyrical translation. Shree plays with words, sentences, and even punctuation. The language refuses to behave. And in doing so, it reflects the core of the story: a woman who also refuses to behave.

There are talking crows, gossiping doors, and sentences that loop and dance. This playful tone is not a gimmick—it’s a feminist tool. By refusing the linear, patriarchal way of storytelling, Shree allows her women (and the story itself) to move freely, to flow, to pause, to interrupt, to return, and to breathe.

In many ways, the novel itself resists control—just like Ma. The narrative does not rush, explain, or justify. It just exists. Like life. Like womanhood.

Caste, class, and the invisibilised

It’s important, though, to note that Ma is an upper-caste, urban woman. She has the mobility, education, and relative financial comfort to explore her freedom. The book doesn’t ignore this—it quietly nods to the people who remain in the margins: the domestic workers, the street dwellers, and the unnamed masses who cannot afford a midlife (or later-life) revolution.

At the same time, by bringing in Rosie and by gently mocking the pretensions of Ma’s own family, Shree shows us the hierarchies that persist—even within feminist spaces. The novel never claims that one woman’s awakening is the same as every other woman’s. Instead, it invites us to look at who gets to rebel—and at what cost.

As feminist readers, this is where we need to lean in. Ma’s journey is beautiful, yes—but it is also shaped by her access to certain privileges. Intersectionality is not just about adding labels—it’s about noticing power, silence, and who gets left behind.

A daughter’s gaze: The limits of modern liberalism

Ma’s daughter, Beti, is an interesting character in her own right. A single woman, a writer, and a so-called feminist, Beti believes she has broken the mould. But when Ma begins to change, Beti is shocked. She had, in some ways, written her mother off—as someone who didn’t understand her modern, progressive life.

But Ma’s journey turns Beti’s assumptions on their head. The novel forces the daughter, who believed she was free, to confront her own limitations. Feminism, the novel seems to say, is not about age, English education, or urban living. It’s about the courage to unlearn.

This layered relationship between mother and daughter also reminds us that feminism is not inherited—it is learnt, unlearnt, and constantly reshaped by lived experience.

Feminism with wrinkles, and without borders

Tomb of Sand is not a traditional feminist text. It doesn’t offer slogans or solutions. Instead, it gives us something far more powerful—a life. A full, chaotic, questioning, flawed life of a woman who dares to begin again at eighty.

Through its playful form and deep content, it invites us to imagine a feminism that is not afraid of softness. A feminism that includes ageing, friendship, failure, and poetry. One that listens to diverse voices, crosses borders, and reclaims history from the margins.

In a world where women’s stories are too often buried, Tomb of Sand unearths them with care, humour, and radical tenderness. It tells us that it’s never too late to choose yourself. And that, perhaps, is the most feminist act of all.

About the author(s)

Anushka Bharadwaj is a journalism graduate from SCMC Pune. She is an intersectional feminist with a deep interest in gender, caste, politics, and mental health. When she’s not writing or reading, she’s usually found lost in poetry, dancing to her favourite songs, or discovering new music—always reflecting on the world through stories.