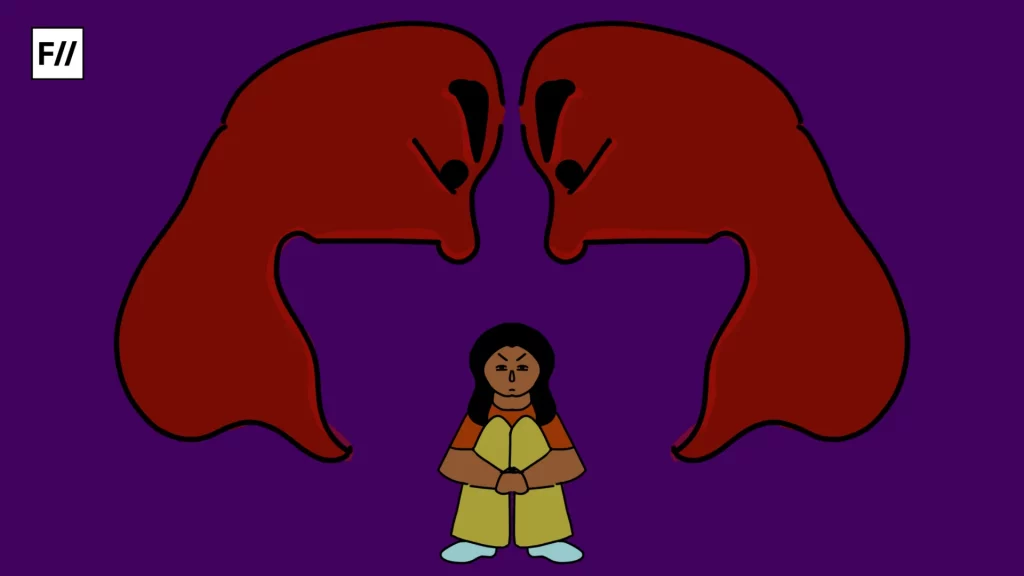

In India, children who are victims of sexual abuse are legally entitled to have their cases heard in specially created courts under the POCSO (Protection of Children from Sexual Offences) Act. Today, there are 725 Fast Track Special Courts, including 392 dedicated exclusively to child sexual abuse cases. It was envisioned as a justice system committed to safeguarding children through child-sensitive means; reality speaks otherwise. Protective mechanisms are mandated, but how often are they truly enforced and followed? Are the youngest and most vulnerable of us all truly protected by the justice system?

Mandated safeguards: the promise of protection

The POCSO Act mandates that the protection of children remains the first and foremost priority. Accordingly, it calls for specific safeguards to ensure that child survivors of abuse are not subjected to further trauma during legal proceedings. Courts that have established child-sensitive atmospheres for vulnerable child witnesses would generally incorporate certain safeguards, as mandated, to ensure that child witnesses are shielded and protected from being exposed to the accused during witness testimony.

Pursuant to Supreme Court directives, district courts are required to establish Vulnerable Witness Deposition Centres (VWDC). The VWDC ensures safeguards such as separate waiting rooms for child witnesses, comfort items, and screens or one-way mirrors during testimony. The witness can also provide the testimony via live video broadcasting from a separate room. Additional provisions aimed at safeguarding the child’s emotional well-being include the presence of support persons – a trusted adult and/or a professional support person – who can provide emotional and psychological support. The VWDC also incorporates closed rooms in some instances to minimise distress and to maintain confidentiality.

POCSO Act and implementation gaps: when protection falls short

Yet, a study published in February 2025 in the International Journal of Law by researcher Luvanath Ramesh found that implementation gaps remain. While these safeguards are implemented in some courts, implementation remains fragmented. Particularly in cases of incest and sexual abuse by a family member, the failure of protective measures can force child survivors to face the accused, who is often a family member, thereby increasing the risk of traumatisation and emotional distress.

It was envisioned as a justice system committed towards the safeguarding of children through child-sensitive means; reality speaks differently. Protective mechanisms are mandated but how often are they truly enforced and followed? Are the youngest and most vulnerable of us all truly protected by the justice system?

Arushi Anthwal, legal counsel at Counsel to Secure Justice, an organisation dedicated to providing access to legal and psychosocial support for child survivors, recalled one instance in which a child was exposed to her mother, the accused. “She became very teary-eyed and very emotional when she just saw her mother coming inside the court. She was placed behind the screen, but she did see her mother, and it was after a long time she was seeing her mother,” Anthwal said, further emphasising that the survivor’s distress highlights the need to implement protective measures effectively. Such stories are neither rare nor exceptional; they serve as a testament to the impact of cracks in the justice system on its youngest and most vulnerable witnesses.

While major courtrooms strictly mandate such safeguards, many district courts in India still fail to enforce them. Court buildings constructed before the enactment of the POCSO Act in 2012 were not designed to meet its specific requirements. For example, older court structures, some over 150 years old, lack separate rooms for victims and other child-friendly facilities. In contrast, newer court buildings have incorporated such spaces, which are now being reasonably well utilised; however, many POCSO court proceedings still take place in the older, traditional buildings.

Despite the POCSO Act and the establishment of VWDCs to ensure child-sensitive proceedings, implementation gaps remain evident.

Before 2025, the Sonipat District Court lacked a fully functional VWDC. Child survivors ended up having to testify in the same room as the accused despite the presence of screens. A VWDC was constructed in 2025 at the Sonipat District Court, but it does not operate as intended. Avaantika Chawla, a child rights advocate, noted that, “Even though there was a VWDC, the same was not functional… so the child would still be sitting in front of the judge and all the lawyers, giving testimony in open court, which is not the mechanism supposed to be followed.” Despite the existence of a VWDC, procedural safeguards continue to be ignored, and child survivors remain vulnerable to further traumatisation – traumatisation that can be prevented even by a small margin. The Sonipat District Court is not an outlier case; many such courts across India exist and remain largely overlooked.

This brings about an uncomfortable truth – that a child survivor’s protection and safeguarding depends on whether they happen to live in a district with courts strictly following mandated protocols, and the ones who don’t go through more harm and trauma than what they already had to go through. Ultimately, this disparity reveals itself to be a matter of luck, determined by geography and the economy, rather than equity under law.

POCSO: Beyond the courtroom

It is critical to note that these failures extend beyond courtroom-specific safeguards. The law is meant for all, yet ignorance and lack of awareness of one’s rights stand as a black mark on this country’s judicial system. Many families remain unaware of their legal rights, which, more often than not, makes them vulnerable to exploitation by the very legal practitioners meant to aid them in receiving justice.

Jweriya Usmani, a former counsellor at Udayan Care says, ‘In all the POCSO cases that you know, they’re supposed to get some compensation but most of these parents did not get any compensation because they did not know about their rights, and they didn’t know that they were going to get some compensation.’

Jweriya Usmani, a former counsellor at Udayan Care, recalled a case serving as an example of the problem outlined earlier. A 13-year-old girl had been sexually abused by her stepfather, and the abuse was revealed when the child’s mother noticed atypical physical symptoms. A medical examination revealed signs of penetration, and the mother hired a lawyer to seek justice for her child. The lawyer, who had promised to obtain the compensation mandated under the POCSO Act for the already vulnerable family, instead exploited their situation by continuously demanding additional payments under the pretext of securing compensation for the survivor. “He just kept charging money from this woman, and she was a household helper who could not afford it, but she still had to pay the lawyer so that she could get some sort of compensation,” Usmani noted. “In all the POCSO cases that you know, they’re supposed to get some compensation, but most of these parents did not get any compensation because they did not know about their rights, and they didn’t know that they were going to get some compensation.”

By functioning in this exclusionary way, justice is functional for very few demographics, and the intersection of trauma, poverty, and judicial illiteracy brings to light how access to justice has remained elusive and limited since it often relies on a person’s geographical position, economic means, and overall level of awareness regarding one’s rights.

In this way, the country’s most vulnerable demographic – children, who represent the future and often already carry the burden of trauma – are subjected to additional harm due to failures in the legal system and its authorities, and their needs are frequently not taken seriously. The failure of the legal system exposes them to harm instead of protection.