Every year on December 3, the International Day of Persons with Disabilities prompts the same cycle of public statements, government messages, and earnest panels about accessibility. Yet in India, the meaning of “access” remains remarkably narrow. For the most part, it refers to physical entry into public infrastructure- railway stations without ramps, buses without lifts, government buildings without tactile signs, or to the most basic level of digital access, such as a website that can be used with a screen reader. This narrowness has become so entrenched that even those who work in disability rights often fall back on it.

There is a reason for this. In India, disability and poverty have long been interlinked. Generations of disabled people have had to spend their energy fighting for survival-level access, not because their needs are small, but because the system rewards only the smallest demands. As a result, a deeper cultural understanding of accessibility remains underdeveloped. While the law recognises access as a right, lived reality shows otherwise. Much of the country’s public infrastructure is still non-navigable, and many government websites remain incompatible with text-to-speech tools. The gap between statute and practice forces disabled citizens to fight repeatedly for what should have been resolved decades ago.

Over time, this landscape shapes how disabled people speak about their own needs. Many internalise the idea that their requests are “too much,” or that asking for more than minimal accommodation is unreasonable. This internalisation becomes a quiet, persistent barrier. It reduces the idea of access to a checklist of ramps and screen-reader-friendly pages, rather than a much broader set of rights that include culture, expression, leisure, and intellectual participation.

Language justice: an invisible access gap

The Alternate-Languages-Tech (ALT) project was designed to address some of these less visible gaps. Supported by the Whose Knowledge? global campaign, the project examines the intersection of language politics, digital access, and disability across India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. When policymakers or technologists speak about digital accessibility for visually disabled users in the subcontinent, they almost always presume English. Screen readers, apps, websites, and formal training materials overwhelmingly centre English as the default.

The ALT project challenges this assumption by showing that the dominance of English is not a matter of preference but systemic coercion. My work in the project focuses on Bengali-language access. In a series of focus interviews with visually impaired users, the pattern was unmistakable. Almost every participant used English for meaningful online interaction. Some described this as their chosen language, but further conversation revealed that this “choice” was shaped by the total absence of viable Bengali alternatives.

One interviewee admitted that he refrains from writing long Bengali posts on social or political issues because typing in Bengali is too labour-intensive. What gets lost, therefore, is not only convenience but the ability to participate in public discourse.

The barriers are extensive. Bengali PDFs, news portals, and academic documents rarely work with screen readers. Tools like InstaReader can handle Bengali images, but they are slow and error-prone. Bengali keyboards such as Avro often fail to work with NVDA. Bengali voice input is so unreliable that it can return completely unrelated or nonsensical text. The effort required simply to produce a coherent sentence becomes exhausting. One interviewee admitted that he refrains from writing long Bengali posts on social or political issues because typing in Bengali is too labour-intensive. What gets lost, therefore, is not only convenience but the ability to participate in public discourse.

Bengali digital books compound this problem. Most are not OCR-enabled, which makes copying quotations for academic use nearly impossible. This is far more than a technical inconvenience. It restricts disabled scholars’ access to the intellectual life of their own language. True access must include cultural and linguistic rights, not just the ability to open a website or listen to a screen reader.

Opening cinema to blind audiences: audio description in Bengali

The lack of linguistic access extends into cinema. While Hindi-language content on platforms such as Netflix has begun to include audio description, Bengali cinema has remained largely inaccessible. Until recently, not a single Bengali film had been made available in audio-described form.

This changed when postgraduate student Arya Moitra produced an audio description track for Satyajit Ray’s Pather Panchali. The project emerged in the Disability in Indian Literature course I coordinated at Jadavpur University during the July–December 2024 semester. Arya undertook the task (entirely without funding) so that blind students, colleagues, and activists could finally experience a film they had only encountered through second-hand discussion. The audio-described version was screened at Jadavpur University in April 2025 and later at BITS Pilani, Hyderabad.

While Hindi-language content on platforms such as Netflix has begun to include audio description, Bengali cinema has remained largely inaccessible.

Since September 2025, Arya and I have begun work on three more audio-described Bengali films available in the public domain: Jamaibabu (1931), the only surviving silent Bengali film; Kalanka Bhanjan (1933), among the earliest Bengali talkies; and Annapurnar Mandir (1936), marking Chhabi Biswas’s entry into cinema. Making these films accessible opens a cultural archive that has long been closed to blind audiences. It also marks a shift toward recognising cinema as part of the cultural commons to which disabled people have full claim.

Crip lit cards: disability as archive and method

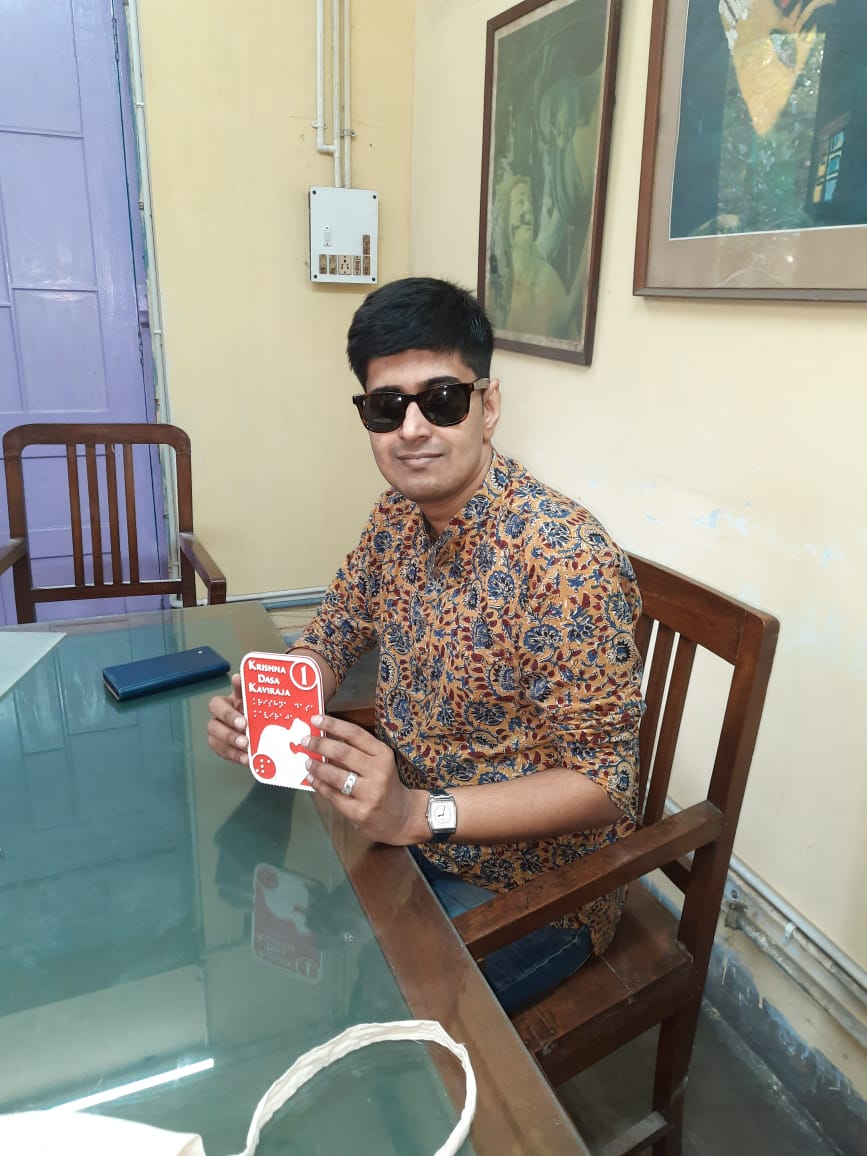

The Crip Lit Cards project, developed at the Department of English, Jadavpur University, is another attempt to expand the meaning of access. Funded by the Global Jadavpur University Alumni Foundation, the project builds a tactile literary archive through a 3D-printed card game. I serve as Principal Investigator, and the game’s 3D design work was led by Mr. Shaswata Bandyopadhyay.

The premise is simple but radical: literary history is usually taught through ableist assumptions, both in content and method. Disability appears as metaphor or tragedy rather than lived experience. Disabled writers, theorists and activists, such as Ved Mehta, Judy-Lynn del Rey, Yoko Ota, Laura Bridgman, and Harriet Tubman rarely occupy central pedagogical space. Crip Lit Cards seeks to change this by making disability the organising principle of both the archive and the game mechanics.

The cards are 3D printed with raised bas-reliefs of the authors, Braille text, orientation textures, and tactile symbols tied to biographical details. This creates a tactile counter-archive where literary authority shifts from printed text to sensory experience. Blind and visually disabled players can read, navigate, and interpret the cards through touch alone.

The gameplay is intentionally cooperative. Players earn points by matching cards based on intersecting attributes, such as gender, disability, historical period, region, or other categories agreed upon by the group. Power cards, depicting queer or transgender figures, introduce additional mechanics that redistribute points, skip turns, or alter the sequence of play. These dynamics encourage emergent gameplay: simple rules produce complex patterns of interpretation, allowing players to build unexpected connections between authors.

The game draws on the idea of misfitting, which argues that disability arises when environments fail to accommodate bodies, not the other way around.

The game draws on the idea of misfitting, which argues that disability arises when environments fail to accommodate bodies, not the other way around. Crip Lit Cards reconfigures the environment so that disabled players fit from the start. It also models crip time through slower, more reflective play, resisting the rapid, competitive pace typical of many card games. In this way, the game challenges compulsory able-bodiedness not only through representation but through structure.

The cultural right to access

Taken together, the ALT project and Crip Lit Cards highlight a fundamental truth: access is not only a matter of railings and ramps. It includes the right to one’s linguistic world, one’s cinematic heritage, and one’s literary traditions. It includes the right to write in one’s own language without fighting one’s tools. It includes the right to learn from archives that do not erase disabled experience. Access is the right to belong culturally, intellectually, and politically.

These projects are small interventions in a much larger struggle. But they suggest what is possible when we stop treating accessibility as a technical add-on and begin treating it as a cultural foundation. To build a more inclusive future, we must begin by expanding our imagination of what access truly means.

About the author(s)

Dr. Ishan Chakraborty (he/him) is Assistant Professor in the Department of English, Jadavpur University. He is a person with Deafblindness,,. His research interests include Critical Disability Studies, Translation Studies, Crip Theory, Language Justice, and 19th-century Bengali and English literature. A recipient of the Abul Kashem Rahimuddin Samman and the State Award for the Empowerment of Persons with Disabilities (2019), he has led projects on audiobooks, marginal pedagogies, and language justice. He currently leads the Crip Lit Cards project, funded by the Global Jadavpur University Alumni Foundation.