If you enjoy sharp television, 2025 has delivered, and how! Many of these standout stories centre on women’s experiences. Feminist writing today blends into structure, tone, and philosophy. The genre has gone past those endlessly competent, selfless protagonists. Instead, it explores power without reducing characters to mere symbols.

Here’s a mix of series that feel fresh: a sex-positive cancer story, a claustrophobic Indian horror, an Ecuadorian stop-motion fever dream, a Spanish rage-opera, and a Korean industry satire. Each redefines what feminist television can be and reshapes our idea of “good” TV.

1. Dying for Sex (English)

Dying for Sex opens with Molly (Michelle Williams) in a therapist’s office. The session is midway. She receives a call. Her cancer has metastasised to Stage IV. No treatment can save her; only time remains. Molly decides to leave her husband and pursue sexual pleasure, something she’s never done before. She accepts all its accompanying risks.

The series, based on Molly Kochan’s podcast, shows her reclaiming agency. Her desire is not just a subplot; it’s where she takes back control over her body. A body that hospitals and family, even well-meaning friends, keep trying to manage. The feminism of the show resides in that insistence. It resides in a woman facing death, still getting to ask what she wants. Even, rather especially, if the answer makes everyone else uncomfortable.

2. Khauf (Hindi)

A woman returns home from a bus ride and discovers semen on her dress. She stares at it for a moment, then strips to wash it off. She scrubs her skin repeatedly as if she can erase what happened. But this is just a routine violation for Indian women. This is a familiar situation for any woman who has to go out every day. The show treats it as such. Khauf takes place mainly in a working women’s hostel in Delhi. The setting may sound protective, but, in the show’s hands, it becomes a pressure chamber.

Inside, Room 333 traps its occupants in literal hauntings. Women are haunted whether they stay or leave, whether they comply or resist—stalkers, gropers, men who grab and run, police who ask what she was wearing. The supernatural becomes almost beside the point. The ghost is simply the most visible predator in a city full of them. The show’s horror lies in how routine these violations are.

3. Women Wearing Shoulder Pads (Spanish)

The show, set in 1980s Quito, is centred on a battle over whether guinea pigs should be food or pets. It’s obsessed with who controls the narrative and whose hands are pulling the strings. A Spanish-language Adult Swim series, the show follows Marioneta Negocios and Doña Quispe. The former is an entrepreneur determined to “modernise” the culture. The latter’s livelihood depends on the traditional economy Marioneta wants to dismantle.

It centres women’s desires (for power, for love) without asking them to be likeable or morally consistent. Men do exist in this world, but eh, they’re mostly decorative. The women are the scheming ones, riding giant guinea pigs into battle. It’s campy, sure. But it’s also a sharp critique of “progress” and who decides what that progress looks like.

4. Rage (Spanish)

Rage opens with that somewhat familiar image. No matter which side of the globe you live on, you’d have seen a woman being told to “calm down.” But then the show decides to say f it. It lets her not calm down. Instead, it follows her into the consequences of finally snapping. Then, it does the same thing with four other women. Ultimately, their lives collide. This Spanish black comedy is built around a simple (and satisfying) premise: five women pushed past their breaking points. Their fallout becomes interconnected like a revenge butterfly effect.

These women aren’t “crazy.” They’re reacting to pressures that are often normalised until someone finally stops taking them on the chin without a word. The series intentionally remixes the grammar of masculine revenge stories. Where those narratives treat male violence as “badass,” female anger has historically been pathologized. Hysterical. Irrational. Rage refuses that framing. Its women are dangerous, yes, but that’s a very reasonable response to systems designed to exploit them. Aren’t there enough narratives portraying otherwise? Narratives where female anger must be “justified” through perfect victimhood?

5. Aema (Korean)

The show is set during the Chun Doo-hwan dictatorship. This was a time when South Korea’s government “liberalised” the media as a pressure valve. This helped in sex and entertainment, distracting from tyranny. In the show, the female body is simultaneously required and reviled. The film industry needs women to strip. They need women to draw audiences. But the moment they do, they’re marked as disposable. The series, based on the making of a notorious erotic film, shows this hypocrisy in one scene after another. Be it through auditions that feel like inspections or contracts that offer no protection.

The show follows two actresses who meet while making Aema. One is a star with hard-won industry knowledge. The other is a newcomer trying to hold onto her principles. The series never romanticises the “liberated” 1980s. Neither does it pretend that erotic cinema was inherently progressive. Women are told they can choose what they want, sure. But every choice comes with attached violence.

6. Asura (Japanese)

In Asura, dramatic confrontations happen at the kitchen table. Four sisters sit knowing that their father has another family. The conversation keeps circling back not to him, but to what they themselves have accepted. Broken promises, lopsided marriages, the emotional labour, all of it passed off as duty. All those familiar phrases come back: “Father works hard.” “Mother keeps the home.” “We mustn’t shame the family.” The home, supposedly their shelter, is the site where women learn to swallow rage and call it love.

The show doesn’t glorify sisterhood into some automatic solidarity. The women here bicker and judge all the time. But as they debate whether to reveal the truth to their mother, they start seeing her as someone who has also been lied to and asked to keep the family’s performance intact. She no longer remains a static figure of sacrifice. Consequently, it shows how patriarchy is preserved through the small, daily rituals that pass for normal to “keep the peace.”

7. Dabba Cartel (Hindi)

In Dabba Cartel, the very things that have kept its protagonists invisible (reliability, the assumption that they’re “just housewives”) are their most potent weapons. No one questions the tiffin-wallahs. Meals arrive on time, for that’s the point. By riding drugs along with the rotis and sabzi, the show highlights just how much unacknowledged power sits inside these feminised systems of care.

The women’s descent into crime is no glamorous transaction with the devil. Instead, it looks like a series of small compromises that coalesce into an identity they no longer recognise, or can no longer deny. What pushed them here? A lack of options, a desire for autonomy, boredom, and revenge? These are some of the questions the show poses. The central argument is simple. If you train women only to serve, don’t be surprised when that training, repurposed, makes them very effective at running things you never intended for them to touch.

8. Delhi Crime (Season 3) (Hindi)

Often, crime series lean into stylised violence and twisty plotting. Delhi Crime, now in its third season, refuses to tread that path, remaining stubbornly plain. That plainness is intentional. The show keeps cutting away from potential melodrama to the aftermath, whether it’s the interviews, the missing reports, the parents trying to steer through police procedurals, or the officers handling several crises on limited sleep.

By not packaging violence against women as entertainment, the series asks you to face the banality of harm. The men who enable trafficking are rarely monsters. They are landlords, minor officials, people you see every day. The state is everywhere and nowhere. It’s present enough to harass, absent when it’s needed. Like its predecessors, this season, too, insists that the horror lies not in the crime scene. It insists that the horror lies in the normalised structures that made the crime possible.

9. The Change (Season 2) (English)

In The Change, the home is a trap. Linda, having spent decades on the domestic treadmill (meals, laundry, emotional management, repeat repeat repeat), decides she’s done. Series 2 follows the spillover effects of its predecessor, as other women begin to wonder why they’ve been holding everything together, and men awkwardly try to adapt.

All this as the entire architecture of “normal family life” begins looking more like a pyramid scheme. Under this scheme, women do all the work, and men collect the benefits. The series swings from surreal pagan rituals to those familiar domestic details, because that’s what it feels like to wake up inside your own life and realise you’ve been performing someone else’s plot. It’s blunt, strange, and oddly hopeful.

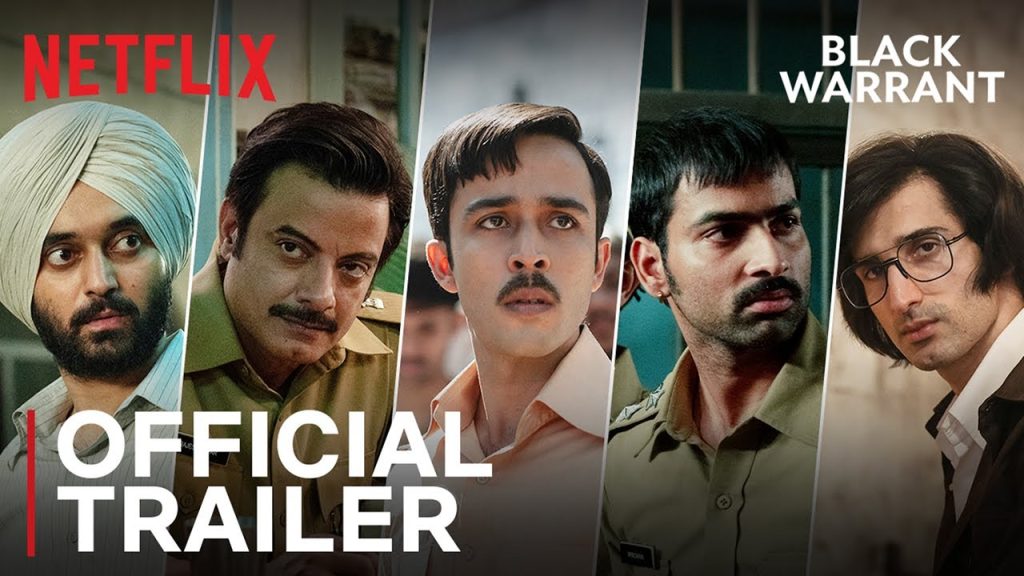

10. Black Warrant (Hindi)

Black Warrant‘s pilot hinges on a minor incident. A dead snake is found in the prison. On paper, it may seem absurd, but in practice, it becomes a contest. Who killed it? Which gang will be blamed? Who profits from the chaos? Who gets crushed because the system needs a scapegoat? That’s the show’s thesis in miniature. Patriarchy pretends it’s all about order. But it’s constantly manufacturing disorder to justify force.

The series, set in Tihar during the early 1980s, follows a jailer guiding through corruption, caste tensions, political violence, and executions. Women barely appear, but the show’s feminism lives in its structural critique. It lives in the way institutions treat vulnerable bodies as disposable. Black Warrant makes that disposal visible in every missing blanket, every bureaucratic shrug, every dismissal, every black warrant.

Conclusion

Across continents and (wildly) different genres, these shows ask the same question. Whose body is it? Who controls what happens to it? Who profits when it’s commodified, policed, haunted, desired, or erased? And most importantly, who gets to tell the story? These shows answer it by refusing to hand the microphone back.

What you get instead is women making choices in worlds that are constructed to punish them for choosing. These are women flawed, furious, funny, doomed, unruly. Women who remain subjects instead of symbols. Their anger stays loud. Their desire remains inappropriate. Their fear stays political. Like all great feminist stories, the works above may not make the world easier to live in, but they make the systems harder to ignore. And that’s where change starts. Change starts in that refusal to look away.

This is by no means an exhaustive or representative list. Suggestions to add to this listicle are welcome in the comments section.