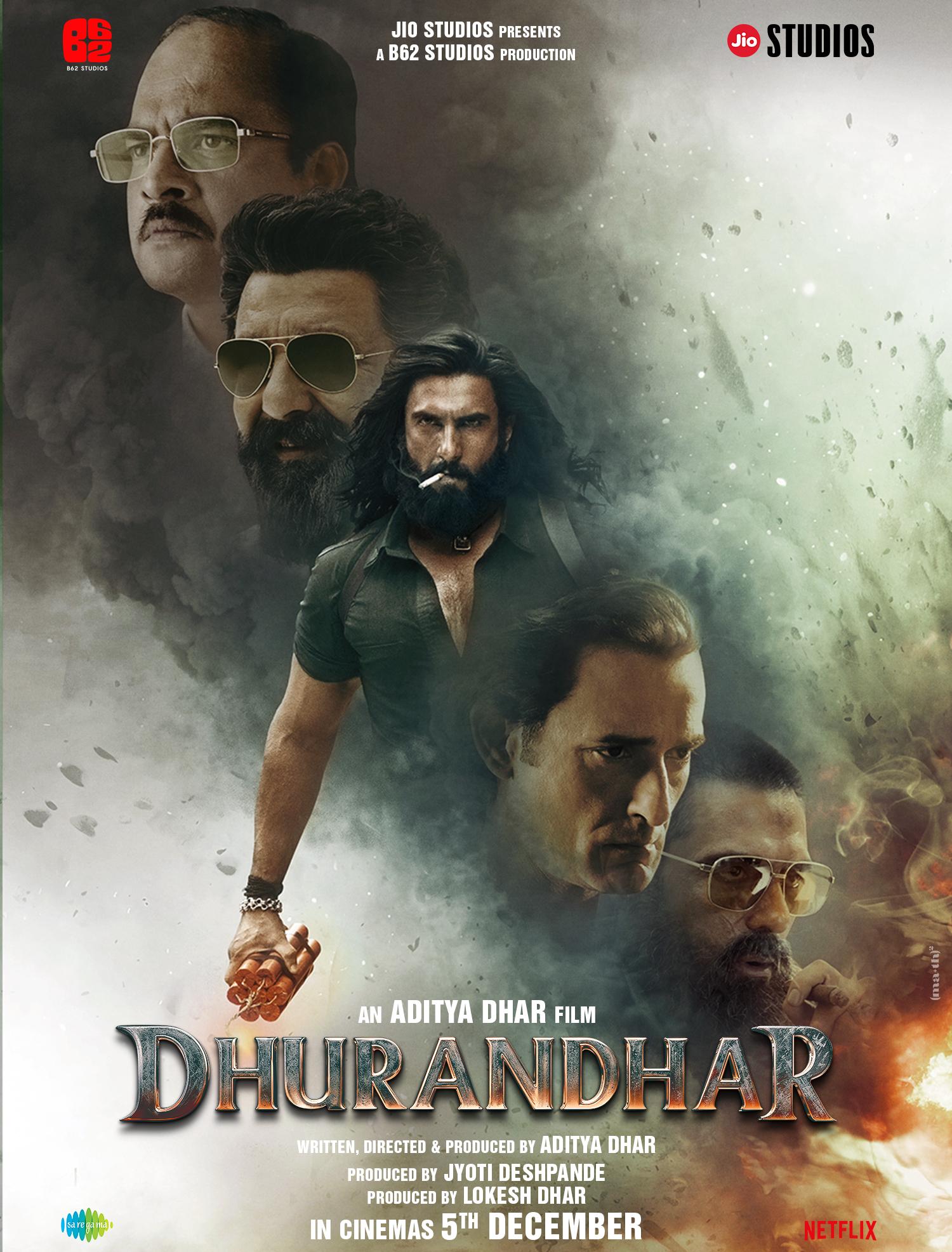

Dhurandhar didn’t announce itself as a provocation, because it didn’t need to. The moment viewers realised that the twenty-year-old Sara Arjun would be paired opposite Ranveer Singh who is forty, the film tiptoed its way around a conversation Hindi cinema has been having for years. Only this time, the audience didn’t sound convinced by the typical answers.

Need vs demand ft. Dhurandhar

Age gaps in Bollywood are not transgressive, they are routine, which makes them all the more scarier. They are so normalised that we are not discomforted by discomfort anymore. They sit comfortably within the industry’s visual grammar.

Two responses to this usual-unusual pairing in Dhurandhar dominated the public discourse among netizens on social media forums: one leaned on principle, claiming that acting is performance and not autobiography; since stories require creative freedom and age differences exist off-screen, so why not on it?

The other response didn’t reject those claims, it sidestepped them. If the story required an age gap, why default to a significantly younger woman yet again? Why not cast a woman in her late twenties, old enough to bring emotional density, young enough to register difference, without pushing the imbalance to its most extreme version?

That question lands harder when placed against these numbers.

The USC Annenberg Inclusion Initiative, in its 2022 Inequality in Film report, found that mainstream cinema repeatedly pairs male leads in their forties and fifties with women in their early to mid-twenties. Age gaps of 10-20 years are not exceptions anymore, they are patterns. Meanwhile, reverse pairings of older women with younger men barely register.

Age gaps of 10-20 years are not exceptions anymore, they are patterns. Meanwhile, reverse pairings of older women with younger men barely register.

The Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media has documented the same imbalance from another angle: women’s on-screen representation drops sharply after 30, while men’s careers remain largely insulated from ageing. This is not oversight, it is preference and a rather misogynistic one.

Debate due to age, but has the debate aged?

Bollywood has defended this preference for decades using the language of creative liberty. But liberty repeated without variation starts to resemble inertia. The industry has reinvented its scale, its markets, even its politics, but its imagination around female ageing remains annoyingly narrow.

At this point, the debate is no longer about whether age-gap stories should exist. It’s about why the industry reaches for them in their most exaggerated form even when the script doesn’t demand it. And especially when alternatives are obvious.

Salman Khan articulated the industry’s thinking with unintentional clarity when asked about age gaps in films. Actors who work together repeatedly, he said, begin to look like an “old pair.” ‘Ab itna kaam kar liya hain hum sab logone ki wo jodi purani lagti hain,‘ he explained, adding that casting someone new restores freshness and a new kind of energy in the film. But we have seen the industry’s moves long enough to know they want this “new” wrapped in a 36-24-36 facade.

Salman Khan articulated the industry’s thinking with unintentional clarity when asked about age gaps in films. Actors who work together repeatedly, he said, begin to look like an “old pair.”

Freshness, in Bollywood’s ecosystem, is often outsourced to younger women.

Responding to the chatter, Aditya Dhar later offered a narrative defence. The age gap, he explained, was not incidental but scripted. The male lead’s character is meant to “trap” the girl, which is precisely why her age was written as 20-21. Any unease, Dhar suggested, would find its resolution in the second instalment. Audiences would “get all the answers” then.

Is discomfort the point now?

Media theory has long explained why such repetition unfolds. George Gerbner’s Cultivation Theory, developed through decades of research published in the Journal of Communication, argues that repeated images shape cultural perception. When audiences see the same dynamics again and again, those dynamics stop appearing unnatural or constructed, they begin to feel natural. Imbalance becomes aesthetic and discomfort becomes ‘ye toh chalta hi hai.‘

Cultural theorist Michael Newman has written about provocation as narrative strategy, and the use of moral unease to generate reaction. In a media economy driven by virality, discomfort is efficient. It circulates faster than subtlety.

Now, Bollywood has done this before. Kabir Singh reframed emotional violence as intensity in relationships, while Animal sold moral dilemma as authenticity, with director Sandeep Reddy Vanga openly stating in interviews that the discomfort was intentional. These films didn’t merely depict unsettling behaviour; they monetised it.

Age-gap casting increasingly operates within the same logic. It introduces friction without interrogation, relying on audience unease to signal “depth.” The problem is not that discomfort exists. It’s that it’s rarely examined.

Aestheticising daddy issues

Feminist film theorist Laura Mulvey explained how positioning women as sites of tension rather than narrative agents, is a common phenomenon in media.

Feminist film theorist Laura Mulvey explained how positioning women as sites of tension rather than narrative agents, is a common phenomenon in media.

These dynamics often slide into romanticised power imbalances of authority reframed as allure, and asymmetry sold as chemistry. Popular discourse collapses this into the term “daddy issues,” trivialising what are, in fact, questions of agency, validation, and emotional hierarchy. Cinema doesn’t interrogate these tensions; it aestheticises them.

Daddy issues are real, and so are age-gaps. But what would it take for filmmakers to flip the script (literally and metaphorically) once in a while? Because on the side of the coin are embedded Mommy issues, but it’s tough to embed the same in the minds of an audience that has been fed the opposite narrative all their life.

Creative liberty vs creative responsibility

This is not a call for sanitised storytelling. Cinema has always relied on discomfort to move forward, when it is intentional and accountable. But creative liberty cannot endlessly substitute for creative responsibility, especially when a reform is not even in the cards yet.

Audiences today are not rejecting difficult narratives, they are rejecting shortcuts and media devices that are meant to fool. And they are certainly noticing when explanation becomes reflex.

Audiences today are not rejecting difficult narratives, they are rejecting shortcuts and media devices that are meant to fool.

Dhurandhar may not be the problem. But it has become the moment, a reminder that viewers are no longer content to be told that something exists because it always has.

The question Bollywood now faces is not whether it can justify its choices. It is whether it is willing to imagine alternatives and trust that freshness can come from storytelling, not just shock.